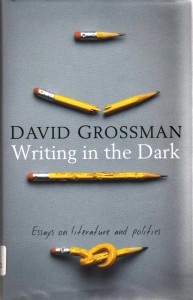

I was attracted to this book – ‘Writing in the Dark: Essays on Literature and Politics’ by David Grossman – because these subjects are also two of my main interests. However, of the six essays, I found those on literature to be actually disappointing and those on politics to be excellent. The last essay is the speech that Grossman made a few years ago when he attacked Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert over his disastrous invasion of Southern Lebanon in 2006 in a war in which the author’s son, Uri, lost his life. In words that have a special resonance in relation to the hypocrisy of some unionists who think they have a monopoly on suffering, Grossman says, “The tragedy that befell my family and me upon the death of our son Uri does not give me special privileges in the public discourse.”

I was attracted to this book – ‘Writing in the Dark: Essays on Literature and Politics’ by David Grossman – because these subjects are also two of my main interests. However, of the six essays, I found those on literature to be actually disappointing and those on politics to be excellent. The last essay is the speech that Grossman made a few years ago when he attacked Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert over his disastrous invasion of Southern Lebanon in 2006 in a war in which the author’s son, Uri, lost his life. In words that have a special resonance in relation to the hypocrisy of some unionists who think they have a monopoly on suffering, Grossman says, “The tragedy that befell my family and me upon the death of our son Uri does not give me special privileges in the public discourse.”

Uri was two weeks short of his twenty-first birthday in August 2006 when his tank was struck by a missile. Just two days earlier, Grossman and fellow writers Amos Ox and A. B. Yehoshua, had pleaded with the Israeli government to reach a ceasefire agreement. The three initially supported limited military action at the outbreak of the war, but then changed their position Israel expanded its operations in Lebanon.

In his essay, ‘The Desire to be Gisella’, he quotes from Sartre’s ‘What Is Literature?’:

“Nobody can suppose for a moment that it is possible to write a good novel in praise of anti-Semitism. For, the moment I feel that my freedom is indissolubly linked with that of all other men, it canoe be demanded of me that I use it to approve the enslavement of a part of these men. Thus, whether he is an essayist, a pamphleteer, a satirist, or a novelist, whether he speaks only of individual passions or whether he attacks the social order, the writer, a free man, addressing free men, has only subject – freedom.”

Grossman, of course, is right when he states that such [anti-Semitic] books have been written but he uses Sartre’s statement as a platform to argue that one can use literature to see things through the eyes of one’s enemy so that perhaps “the enemy gradually ceases to be our enemy”.

“These are some of the counsels that literature can offer to politics and to those engaged in politics, and in fact to anyone coping with an arbitrarily and violent reality.”

He appeals to Israelis to view things for a moment from the Palestinian perspective: “For once, look at them not only through the crosshairs of a rifle or a roadblock. You will see a nation no less tortured than we are. A nation occupied and oppressed and hopeless. Of course the Palestinians are also to blame for the dead end. Of course they had a part in the failure of the peace process. But look at them for a moment in a different light. Not only at the extremists among them, those who have an alliance of interests with our own extremists. Look at the overwhelming majority of this miserable people, whose fate is bound up with ours whether we like it or not.”

Grossman attacks the injustice of the “settlement enterprise” in the Occupied Territories as both morally wrong and wasteful, and speaks of Israelis having “a sense of injustice and guilt. He says, “I would like to hope that relinquishing the Territories and ending the Occupation, with all these entail, will restore most Israelis to the authentic emotions of their identity. Then, for the first time in years, perhaps since the beginning of political Zionism, since the various borders were drawn for the soon-to-be state and then for the State of Israel, there will be an overlap between the geographical borders and the borders of identity.”

He says, “we, the Jews, who have always regarded power with suspicion, have become intoxicated with power ever since it was given us. Intoxicated with power and with authority, and afflicted with all the diseases that limitless power has brought to nations far stronger and more stable than Israel. Unlimited power brings unlimited authority and a virtually unhindered temptation to hurt the helpless, to exploit them economically, to humiliate them culturally, and to scorn them personally…

“We know that prolonged existence in a state of hostility, which leads us to act more stringently, more suspiciously, in a crueller and more “military” manner, slowly kills something within our souls and finally hardens like an internal mask of death over our consciousness, our volition, our language, and our simple natural happiness.”

He dreams of a time “when the State of Israel finally has permanent, stable, defensible borders, recognised by the UN and by the entire world, including the Arab states, the United States, and Europe. Borders that will be negotiated with former enemies out of mutual agreement, rather than drawn unilaterally and coercively – as Israel is doing today with the wall it is building around itself. The meaning of the new borders will be security. It will be identity. It will be home.”