Wrote a feature for Monday’s edition of the Andersonstown News. Title of article: ‘Writers Block While The Writer’s Blocked’

Brendan Behan once said, “I only take a drink on two occasions: when I’m thirsty and when I’m not”.

Sounds hilarious until you consider that he died at the age of 41, and was probably past his best at the age of 35 when he published ‘Borstal Boy’.

The relationship between alcohol and writers has been well documented as has whether drink/drugs liberate the artistic soul. Of the USA’s seven Nobel Literature Laureates, five were alcoholics.

Notably, every generation comes up with its own expression for its excesses, from ‘the roaring twenties’, to the age of ‘wine, women and song’ to ‘sex, drugs and Rock ‘N’ Roll’.

I am not sure of the circumstances under which Shane McGowan wrote ‘Fairy Tale Of New York’, when he still had a tooth in his head and could steadily hold a pen, but certainly in recent years he has never observed or replicated anything as gritty or as powerful as his first musical poem.

One of the most effective videos therapists could probably show in rehab clinics is of a drunken Amy Winehouse trying to sing and stand simultaneously. As Kurtz remarked: “The horror! The horror!”

Last week I was in the company of Irvine Welsh, author of the cult novel ‘Trainspotting’. Irvine is much taller than I expected, healthier and younger-looking than in his photographs and is working on the prequel to ‘Trainspotting’.

If you have seen the film or read his novels you will know that many of his characters are heroin addicts, cocaine abusers and alcoholics. It should come as no surprise then to learn that Irvine was drinking by the age of 14 and was taking speed by 17.

After his reading, as part of Féile, we went to my house for a glass of wine. I asked him who his favourite authors were. He mentioned Evelyn Waugh.

I thought the contrast between Irvine’s working-class upbringing and Waugh, who came from a comfortable, middle-class family, was Oxford-educated and knocked about in aristocratic and society circles couldn’t have been more contrasting.

Waugh could be very funny and wrote that wonderful novel, ‘Brideshead Revisited’. In his diary he tells a story about painstakingly trying to teach English boys Irish history only to be rewarded with this answer to a question about the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party: “Parnell was an Irishman in Victoria’s reign who was murdered in Felix Park because of a divorce.”

But Waugh was also an addict – an alcoholic – who died at the age of 62. His accounts of his bingeing seem incredible: “I am at the moment just recovering from a very heavy bout of drinking… Next day I moved to 40 Beaumont Street and began a vastly expensive career of alcohol… Next day I drank all the morning from pub to pub… I then drank double brandies until I could not walk… I fell out of a window and then relapsed into unconsciousness…”

Alcoholism and drug abuse among writers is more prevalent than among many other occupations. Alcoholic writers themselves often peddle the myth that inspiration and creativity can best be found at the bottom of a bottle, and though there might be occasional proofs (if you will excuse the pun) of this the weight of evidence is to the contrary.

“Good writers are drinking writers,” said Hemingway – who blew his head off with a shotgun.

“I wouldn’t recommend sex, drugs, or insanity for everyone, but they’ve always worked for me,” wrote Hunter S. Thompson (‘Fear And Loathing in Las Vegas’) – before he too went on to commit suicide.

Twelve centuries before Thompson was even born, the Chinese poet Li Bai, a.k.a. one of the ‘Eight Immortals of the Wine’, tried to embrace the reflection of the moon in a lake whilst drunk, fell in and drowned.

Coleridge was an opium addict when he wrote ‘Kubla Khan’ and died of respiratory problems and an enlarged heart brought on by prolonged opium usage.

John Lennon wrote ‘I Am The Walrus’ while on acid and the title is a dead giveaway – though it was a maniac who took away his life.

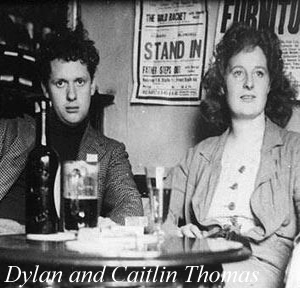

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, an alcoholic from he was 20, met his future wife Caitlin in a pub, and their marriage was stormy and abusive, fuelled by alcohol. “Ours was not only a love story, it was also a drink story,” she wrote. “The bar was our altar.” As he lay dying in a New York hospital she burst in drunk and shouted, “Is the bloody man dead yet?”

In his well-received novel ‘The Truth Commissioner’, David Park’s character Henry Stanfield comically/cynically refers to the North as “a godforsaken land … where a ship that sank and an alcoholic footballer are considered holy icons”. Ouch!

A few years ago, Marion Keyes spoke at Féile an Phobail about her battle with alcoholism and clinical depression and how writing actually helped her overcome both. And, of course, Pete Hamill, who also once spoke at Scribes, described the toll that drink took on him in his powerful memoir, ‘A Drinking Life’.

So, as I sit at my word processor, I am speedily transported on to a higher plane of creativity with a glass of semi-skimmed milk in one hand and a dark Bourbon biscuit in the other, recalling those cautionary words of Scott Fitzgerald, who died of alcoholism, aged forty-four:

“First you take a drink, then the drink takes a drink, then the drink takes you.”

Amen