Have just reviewed for a loyalist website (longkeshinsideout [2]) former UVF prisoner, Plum Smith’s fascinating book about his time as a prisoner in Crumlin Road and Long Kesh. Here it is.

SOME years ago I was on a panel in the Waterfront Hall along with Billy Hutchinson of the Progressive Unionist Party. We were discussing a play we had just watched, The Chronicles of Long Kesh. Billy and other loyalists in the audience took great exception to the depiction of their prisoners in the play, and objected to prison experience and indeed the conflict generally being monopolised as mainly a dominant republican story (on stage, in literature and in film).

Of course, the required response was for loyalists to take control of their own story and write their own accounts. That process was already underway, for example, in such a work as Reason To Believe by former loyalist lifer, Robert Niblock, a play which was well-received and reviewed.

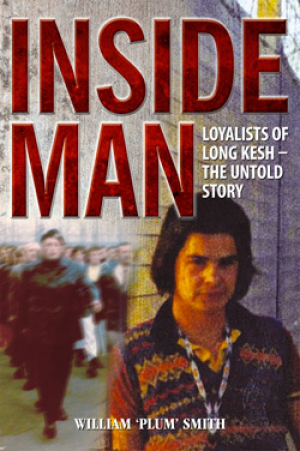

I was thus glad to hear a few weeks ago that former UVF prisoner William ‘Plum’ Smith had written a book and I went along to the packed launch in Crumlin Road Prison. I have to say, I was very impressed and enjoyed Inside Man, about Plum’s five years in prison for the attempted murder of a Catholic, Joseph Hall, whom he shot in Unity Flats. ‘Enjoyed’ might be misinterpreted as mischievously delighting in the woes and suffering of an opponent. But what I mean is that his is a very honest, human account, and at times a very funny account, of life in prison and his life before that: what made him a loyalist who was prepared to go beyond parading and take up arms against what he perceived to be the enemy (however I disagree with that description).

It is a book that nationalists and republicans should read in order to learn about the loyalist mindset which is too easily dismissed and stereotyped. Obviously, I would take issue with his analysis of what was happening in 1968 and 1969 because I think unionism misread the Civil Rights Movement and was fairly complacent because it had power and could exercise that power. That power had worked for fifty years so why change tack, why reform, why make any concessions? But once we were plunged into violence then every past slight, every insult, every act of past discrimination and every memory of injustice, and the greater sense of alienation, would feed the explosion that was to become the IRA and its long campaign.

Plum Smith was born on the Shankill Road in 1954, so he and I are almost coevals (I was born in Andersonstown in 1953). His father often had to go to Scotland or England when work was slack in the North, as had my own father and neighbours.

Seventeen-year-old Plum was first arrested during a riot in June 1971 and was subsequently sentenced to six months in Crumlin Road Prison. There he was attacked by republicans who outnumbered the loyalists. He was only out seven months when he was rearrested and this time convicted of the attempted murder of Joseph Hall and sentenced to ten years imprisonment.

“The IRA, Nationalists, Republicans or Catholics were killing people in the Protestant Community and I was retaliating in kind. I had neither sense or remorse, nor a sense of loss of freedom or how long I would lose that precious freedom. I had no regrets, nor did I contemplate what the future would hold.”

In August 1972 he was among nine loyalist prisoners placed in a remand cage in Long Kesh which the year before had opened as an internment camp. In the cages around him were up to 500 republicans. He was to return to the Kesh as a sentenced prisoner with political status where the undoubted leader and major influence was Gusty Spence. Initially, loyalists from different groups were all mixed together but later, as factionalism arose, each group (UVF, UDA) demanded its own cages – a development that Plum Smith regrets because he believes it led to even more feuding between the groups.

Earlier in 1972, as a result of an IRA hunger strike, the British government had introduced Special Category Status which was political status or POW status in all but name. It was perhaps the most progressive penal concession made by the British during the conflict and was to lead to ‘relative’ calm in the prisons. (No prison officer had been shot during this time.) It was withdrawn by the British in 1976 with devastating consequences that led to a blanket protest and the hunger strikes and deaths outside and inside the prison – only for the British government, years later, to again concede political status after its disastrous experiment failed.

This memoir is a mine of information about the discussion papers produced and the level of debate which went on inside the loyalist cages. They advocated a Bill of Rights, reform of the RUC, integrated education, cross-border cooperation in non-contentious areas (tourism, regional development, agriculture, etc) and instead of power-sharing, ‘Equal Responsibility’ (which was probably power sharing!). Whether the workshops, the literature, amounted to anything of substance in the end is open to opinion, but he establishes the fact that there was a culture of political engagement and self-examination.

Looking at old photographs and sometimes scratchy silent Super 8 film of these men in prison, what I do find alien (and perhaps it is just me) is the apparent fetishism with military discipline and military display within loyalist cages.

I am not sure of the degree of militarism (marching, parading, saluting, bed and hut inspections) that went on inside the cages of republicans serving prison sentences. What I do know, is that among us internees at the lower end of the camp, the drilling that went on in Cage 2 bored me and the majority of others to tears. We’d rather watch Top of the Pops and M.A.S.H. than practise drill in a freezing Nissan hut. But from Plum’s account the prisoners, apparently willingly, enthusiastically, were up for marching at the crack of dawn and had the best polished shoes in Ireland! (Sorry, the UK!)

He also reminds us of escapes by loyalists – of which I was unaware – the first of which was in 1972 from Crumlin Road Jail.

He epically tells the story of the republican burning of the camp (which was now huge, consisting of 21 cages) from the loyalist perspective and of the incredible degree of cooperation (a non-aggression pact between prisoners) that existed that night. The gas affected every area and the republicans were surrounded and being beaten by overwhelming numbers of riot troops.

“Republicans began moving their injured out of the football fields back into Phase 6, just outside our compound. We used the wire clippers to cut the fences and make entrances into C19. Those who we thought were the most seriously injured we brought into our compound, into the wooden study hut and gave them first aid using the medical supplies we had procured the night before.”

The following day he watched as soldiers beat prisoners: “I have never seen such brutality in all my life.” The republican prisoners were to be given two pieces of bread and milk but the soldiers put the bread and milk in a heap, tramped and spat on them and then made the prisoners run a gauntlet of batons to get their food.”

A loyalist rescue party, incredibly, also took prisoners to safety.

Three years later, after the withdrawal of political status, loyalists were on the blanket protest for a time but came under pressure to call off the protest because of its identification with their enemy – the IRA. I wonder what would have happened to the prisoners had they pooled their opposition to the withdrawal of status? Would the British government have folded earlier than they did? Would the prisoners have found common humanity in common ground? Would it have helped bring down the walls that separated them a little?

There was, of course, the establishment of a Camp Council in the early 1970s made up of all republican and loyalist factions. Whether this had potential to mature into something significant – a lobby, finding consensus, engaging in acts of conciliation – we will never know because it was thwarted by the NIO who were moving towards the strategy of ‘criminalisation’.

I can absolutely identify with Plum’s graphic descriptions of life behind the wire, the raids, the deceptions employed to get ‘one’ over the governor and staff, including the smuggling into the jail of a transmitter! He captures the atmosphere, the personal suffering, the death of a prisoner through medical neglect, his learning of the Irish language, loyalist involvement in further education, the joy of comradeship but also the travails of imprisonment, especially the difficulties for one’s loved ones.

They made long journeys, visited week-after-week, waiting for long hours, often experiencing humiliating searches for a half-hour visit which was often cut short at the whim of a prison officer who alleged that smuggling was taking place (often a bit of tobacco, the historic currency of prisoners). Families lost their breadwinners and the prisoners often ‘lost’ their spouses and their children, especially those prisoners serving lengthy sentences.

Released in 1977 Plum Smith became a shop steward with the ITGWU, remained a determined advocate on behalf of loyalist prisoners and in 1994 chaired the press conference when the loyalist ceasefire was announced. These might have been the golden days for the Progressive Unionist Party when it looked like it was on the verge of making a major and sustained breakthrough but through numerous mishaps, and the tragic death of the talented David Irvine, the party’s support fell, and with it, I suppose, came disillusionment and some internal chaos.

Plum Smith has always been amiable and accessible and prepared to cross the peace line. He has been an honest witness but also a reflective protagonist. After the signing of the Good Friday Agreement he was one of his party spokespersons selling the deal to the public and addressed a meeting at a women’s centre in Belfast. After his contribution an elderly woman got up to speak in favour of the Agreement and swung many doubters in the room. He writes:

“A few weeks later I met the woman who had organised the meeting and I asked her who the lady was, did she know her? She said to me, “Plum, that man you shot all those years ago was her son.” I was taken aback. She then said that the lady had expressed her joy that I had been so positive about the agreement and supported me in the work I was now doing. What can you say to that? Her face never haunted me, it humbled me. Her dignity and compassion was so elevated. She was someone’s mother and my victim was someone’s son.”

Plum Smith in 1971 went inside as a kid. But he came out a man. A man dedicated to his community, to reconciliation and peace.