My imagined ‘letter’ from Reggie Dunne to the IRA after the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson in 1922, and a recording of the letter being read by the actor Will Howard, will remain on display at Reading Prison for a further two months after the exhibition was extended until December 4th. It is part of the ArtAngel project around themes of imprisonment, in particular the experiences of Oscar Wilde who was incarcerated in Reading for two years.

On 22nd June 1922, Sir Henry Wilson, the unionist MP for North Down, and chief security advisor to the newly-established Northern Ireland state, was assassinated in broad daylight by Irish republicans outside his London home.

On 22nd June 1922, Sir Henry Wilson, the unionist MP for North Down, and chief security advisor to the newly-established Northern Ireland state, was assassinated in broad daylight by Irish republicans outside his London home.

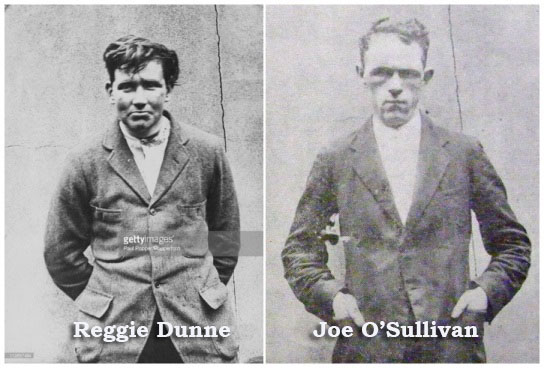

Two men, English-born of Irish parents, were charged with his killing.

Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan were former British soldiers who had both been wounded in France, O’Sullivan losing a leg at Ypres.

In Southern Ireland the IRA had split over the terms of the recent Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Michael (Mick) Collins headed a provisional government against a breakaway IRA garrison led by Rory O’Connor which wanted to fight on.

Then came the assassination of Wilson.

From Wandsworth Prison Reggie Dunne sends a smuggled letter to the leader of the IRA in London.

18th July, 1922

Commandant. It’s all but over. Joe and I are to be hanged in three weeks’ time, on 10th August. The trial lasted three hours, then the jury were out. As our solicitor was trying to keep our spirits up in the holding cells, the sergeant shouted through the bars that we were wanted back up in court, they had reached a decision. The jury took just two minutes to find us guilty! Even the sergeant said it was the quickest verdict he had known but that everybody was in a rush today to catch “the biggest wedding of the century”, Lord Louis Mountbatten was getting married to some wealthy English heiress.

So, we left the Old Bailey for here much earlier than anticipated. But that shouldn’t have mattered, nor affected your plans. As we had known we would be, and as had previously been described to you, we were handcuffed and locked in the back with two guards for what we thought was our last journey. The driver was repeatedly blowing the horn at pedestrians. At one stage the fool opened the grill and took great delight in telling us that there were thousands flocking the streets, out to kill us. By our bearings we thought we had just crossed Blackfriars Bridge. Shortly after, there was a dull thud and we all shot forward as the van suddenly braked. The driver was shouting and we could see our guards’ faces turn pale. Joe and I nodded to each other, braced ourselves, and were convinced, “This is it”. I thought of my parents and the young woman whose heart I’ve broken. Then, the driver cursed the dog that must have darted onto the road and across our path. We could hear the old thing whimpering and children crying. After a few moments we resumed the journey.

Commandant, when escape plans fell through, we meant it when we told you to blow us up in the van. You were our last hope. If the Mountbatten wedding or extra police on the streets thwarted the plan, then there’s nothing we can say, no complaint can we make. But I would not like to think that you had qualms about despatching us this way. Don’t misunderstand me. Joe and I will go to the gallows with our heads held high – and our secrets well kept – but we would have preferred to deprive these people of the pleasure of hanging us.

Churchill’s claim that we were caught with papers linking us to Rory’s garrison was a downright lie. There were no documents on us.

We kept our mouths shut in Gerald Road Police Station. Even our interrogators initially hadn’t a clue who we were. Joe was charged under the alias ‘John O’Brien’ and I as ‘James Connolly’. You should have seen the mortified look on the Detective’s face when he discovered that they had already shot ‘James Connolly’ in 1916! I laughed when he had to re-arraign me under ‘Reginald Dunne’.

But he came in the next day all cocky and threw down the dailies, inviting me to read them. I never flinched. He read out Rory’s denial of involvement, which I expected. But to be honest, the condemnation of the killing and the strong language from Mick’s spokesman was bloody hypocritical. The Detective then gleefully read out Churchill’s ultimatum to Mick that if he didn’t deal with Rory’s defiance of the Treaty, the British army would. That put me in good form, as I thought, yes, our plan is falling into place.

But you can guess how sick Joe and I were when Mick bowed to Churchill and attacked the garrison, capturing Rory and his men. If Churchill had tried that every volunteer would have flocked to Rory’s cause. And now there are attempts to blame Joe and me for the fighting that has now broken out. We can see through that but our poor families are badly shaken and confused and have asked what we thought we hoped to achieve. And of course because our visits are closely monitored we cannot speak plainly to them.

One day, be it years from now, when the dust has settled, the rest of the world can be told that Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan were not mavericks or renegades but were soldiers of the Republic on official business aimed at killing a tyrant and re-uniting the IRA against the common enemy.

I’ll not see Joe again, until the morning of 10th August. I’ll miss him over the next few weeks. He holds himself responsible for my arrest and, now, for my death. I remind him that it was me who picked him for the Wilson job and that I knew well beforehand that he was no ‘sprinter’! That made him smile a little. After the shooting a hue and cry was raised and we had to run in a different direction than planned, away from our car. Let our driver know, we do not blame him. We were chased by a hostile crowd and by policemen blowing whistles. Joe, because of his war wound, losing a leg in France, was much slower than me and was quickly overtaken by the mob shouting, “Lynch him!” When I looked back I could see that he had fallen and was being pummelled by the mob. We were always in this together and I would never have left him. I turned back and threatened the crowd with my Webley and could have taken a few had I wished. I was overpowered from behind and beaten unconscious before we were taken into custody.

In court we admitted shooting Wilson but refused to plead, so a Not Guilty plea was entered on our behalf. One of our prosecutors was a fellow called Humphreys who I found out had in his younger days acted for Oscar Wilde in the same court.

Our solicitor asked the judge could I read out a brief statement. The judge asked to see it. His jaw kept dropping the further he read, then he said he was impounding it because it was nothing but a political manifesto! We then instructed our defence team to withdraw.

That forced the judge to address us directly. He asked if we had anything to say before he pronounced sentence so I spoke. I said I was sorry that the jury was denied the chance of hearing our statement which explained why two former servicemen with exemplary war records, both wounded in action, would kill their former commander.

Try and get what I said published as it is important that the public hear the truth about how our struggle for freedom was subverted by Wilson and his ilk.

I said that for England I had killed many German soldiers, most of whom were conscripts. Ordinary working men, farmers, students and teachers – teachers just like myself. I and thousands of other Irish soldiers volunteered to fight in the European war. Thousands of our fellow countrymen died for Britain because we were told that if we did so then Ireland would be treated fairly and given her rights at the end of the War. But this was a huge lie. We were praised to the high heavens, in press and from pulpit, for savaging men by bullet and bayonet. But for killing one man for Ireland – a scourge, who encouraged the British army to mutiny against Irish Home Rule, who divided our country, who had the blood of thousands on his hands, and who had been rewarded and elevated and indulged by Britain for his role – we were being slandered as criminals and condemned to die on the gallows.

When they took two minutes to find us guilty, Joe said with that dry wit of his, “Your speech certainly won them over, ‘Mr Connolly’. You were very persuasive!”

Shortly afterwards we were taken back to here from where we shall not be moving. Any appeal will be heard in our absence.

We have a bully of a warder. ‘Kitchener’ is his nickname. Apparently, he gave himself that name when Lord Kitchener’s ship went down. Everyone is afraid of him. He constantly gives us a rough time and he tries to goad us.

“I see Michael Collins has disowned you and is now shooting your comrades in Ireland,” he said, when news came through about the fighting in Dublin. When he cracks what he thinks is a joke he belly-laughs until he almost falls over. He soon shut up when I asked him what regiment he had fought with. Turns out that the white feather coasted through the war in charge of the borstal wing while Joe and I and our comrades were up to our eyes in muck and blood in Flanders.

When we found that out we turned the tables on him. I shouted across the landing to him for all to hear. “Hey Kitchener! Is it true, Your Country Didn’t Need You?”

“Be fair,” said Joe. “He had a terrible bunion in his big toe which meant he couldn’t retreat.”

When we were first being assigned our cells some weeks ago and led through the gaol we were spat at and called murderers and cutthroats by the other prisoners. But that was to change, especially when they saw our attitude to authority. Today, when we got back after court we were allowed briefly into our own cells to gather some things before being moved to the condemned cells in E-Wing. It was strange being taken down through the landings. Even though the environment was alien on Day One, our wing had become familiar to us in the past few weeks as relations with the other inmates thawed.

Old Syd, the orderly, Wandsworth’s veteran jailbird, stopped mopping, came forward and pressed his precious ration of tobacco on Joe, against regulations. Kitchener bawled like a madman and ordered a warden to place Syd on punishment. From behind their doors prisoners banged their tin mugs and shouted messages of support to us. Kitchener warned us not to reply or encourage ‘contumaciousness’, his favourite word, or we would be punished!

Joe said with sarcasm, “How punished? What are you going to do, draw and quarter us!”

Each day on the way to the exercise yard we passed Oscar Wilde’s old cell mid-way up the long gallery, where he had contemplated suicide before being moved to Reading Gaol. As we passed it tonight for the last time I thought of his torturer, Sir Edward Carson, the man who opposed our freedom and helped divide Ireland. A man whom we should have shot in 1920 when we had the opportunity.

The man who shall deliver this to you is trustworthy and expects no reward. But please give him something because he has a young family and is taking a great risk which would land him in gaol and make him unemployable in this society. I have taken the opportunity of including another letter. It is for a friend, a young woman I had been seeing, though no one but Jack knew about this or is aware of her identity. She was only vaguely aware of my activities and I feel a great guilt for potentially compromising her and placing her in jeopardy.

Commandant, the organisation must promise, that one day, be it in five or fifty years’ time, our remains are removed from this prison yard and that we are laid to rest in the soil of Mother Ireland. That is where we want to be buried, even though we were born and grew up here in London. This is not our home.

And so it is goodbye, my old friend and comrade. Many have trod this well-worn path, the path to Freedom, before me. I love my countrymen and I love Ireland and I trust that God will have mercy on the souls of Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan.

Up The Republic!

Footnote

Dunne and O’Sullivan were executed on 10th August, 1922. Twelve days later Michael Collins died in the civil war which engulfed the south of Ireland, killed in an IRA ambush.

Forty five years after their execution, the bodies of Dunne and O’Sullivan were exhumed from Wandsworth Prison and re-interred in the Republican Plot, Deansgrange Cemetery, Dublin. Sean MacStiofain, himself English-born, and who two years later was to become the Chief of Staff of the reorganised IRA after the split in 1969, gave the main oration. An IRA firing party emerged from the crowd and fired a volley of shots over the grave of Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan.