Mary Ward, whose son Peter was shot dead by the UVF in 1966, died yesterday, aged 97. In an interview two years ago, on the fiftieth anniversary of Peter’s death, his sister Bell spoke about her mother as “a holy woman” who “never missed Mass and always went to Novenas and said her prayers every night.”

By the late 1950s the IRA border campaign had fizzled out and republicans were turning their attention to politics and peaceful agitation (which prefigured the formation of the Civil Rights Association in 1967). In the spring of 1966 Gerry Fitt, in a bitterly fought contest, took the West Belfast seat of Ulster Unionist James Kilfedder (who had been supported by Ian Paisley), and republicans in West Belfast, in a parade banned by Stormont, commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Rising in a march to Milltown Cemetery.

So, the North was relatively quiet when loyalist gunshots shattered the peace.

At the age of thirteen I, like thousands of others, watched Peter Ward’s funeral along the Falls, the second victim of violence within two weeks following confirmation, after an exhumation, that John Scullion from Clonard had also been shot, though this had been denied by the RUC.

Some of Peter’s workmates had also been shot: Liam Doyle from West Belfast was shot in the leg and Strabane man Andrew Kelly suffered abdominal wounds in the gun attack.

The UVF’s Gusty Spence (who died in 2011), and two others, were given life sentences for their part in the killing.

In an interview in the Irish News two years ago Bell Sheppard said that if police had warned people that a sectarian murder gang was on the loose in Belfast her brother may not have ventured into the loyalist area. Bell, who was eight months pregnant at the time of the attack, named her son Peter in memory of her eighteen-year-old brother.

“I remember my brother as being good and kind and a great person altogether. I think about him all the time,” she said.

In 1974, after I got married, I got to know Mrs Ward well when we became next door neighbours when I moved into 90 Beechmount Parade.

Twenty years ago when the late Seando Moore and I were writing a small book, Green River, about those from our area who had lost their lives in the conflict, I interviewed Mrs Ward about Peter. Below is the interview from that book.

“Peter and I were very close. On one occasion when I went to visit relatives in America he fretted the whole time I was away. I was widowed at 28 and had a daughter and three sons to raise. Peter was born in Bingnian Drive, Andersonstown in 1948 but a few years later we moved to 53 Beechmount Parade. My mother and father lived in No. 92.

“Peter started work in the mill when he was 14 and even joined the British Army for a while, as a lot of the young lads did in those days before the Troubles. But being away broke his heart. He came home for four days leave at Christmas and didn’t want to go back. I was afraid of the Redcaps arresting him and beating him up so he had to go back. He went away on a Saturday night and I got a letter on Tuesday. He said, ‘Mammy, if you could, £20 will buy me out.’ I wired him the money and got another letter thanking me all roads. He was left-handed but a beautiful writer.

“I was on my way to work early one morning and opened the door and there he was – tall and lovely! He was wearing a black raincoat and a black polo-neck jumper and he threw his arms around me and said, ‘Mom, I’m glad to be back. I’m never gonna roam anymore.’ I never went to work that day.

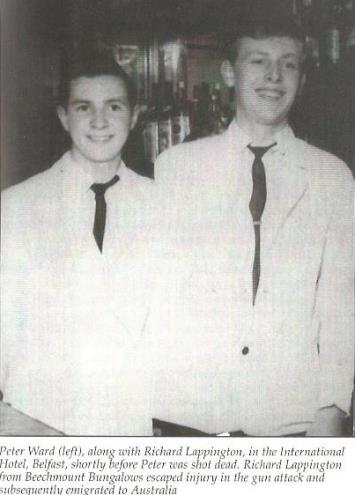

“He went for a job interview in the International Hotel and the owner, Mr McGratton, took an instant shine for him, he later told me himself. He liked the way Peter walked! Peter had no hatred against anybody, any religion or nationality. The only thing he ever said was one night about a week or two before he was killed. I was making his dinner when the news came on the television. Shortly before this Paisley had been stirring things up and had started trouble at Cromac Square. On the TV was news of John Scullion’s body being dug up.

“He went for a job interview in the International Hotel and the owner, Mr McGratton, took an instant shine for him, he later told me himself. He liked the way Peter walked! Peter had no hatred against anybody, any religion or nationality. The only thing he ever said was one night about a week or two before he was killed. I was making his dinner when the news came on the television. Shortly before this Paisley had been stirring things up and had started trouble at Cromac Square. On the TV was news of John Scullion’s body being dug up.

“‘Good God. Look what they’re doing, lifting that poor lad’s remains out of the grave,’ I said. They had said he had been stabbed but his family insisted he had been shot. His shoe had been found in an entry with a bullet hole in it. It turned out he had been shot by the UVF.

“Peter said, ‘That Paisley must be a bad man, mammy.’

“I was over in my daughter Bell’s house. As I was walking home I thought to myself, it’s a beautiful summer’s night. Peter was at work in the International. My Thomas was also working in a bar. After closing time Thomas came in. I said, ‘Peter’s not home yet.’ He said, ‘He’ll not be long.’ We went to bed but I couldn’t sleep. I was looking out the window. In the early hours there was a knock on the front door. It was a Sunday, June 26th. I came down. Fr Murphy from St Peter’s was standing there.

“‘Mrs Ward?’

“‘What is it, father? I’m waiting on my son coming in, Peter. He wouldn’t have me worrying.”

“‘Have you anybody in the street you can go to?’ he said.

“‘My father. But he’s old. What’s the matter?’

“‘Mrs Ward. I’ve a bit of bad news about your son Peter.’

“‘What is it!’

“‘Peter was shot.’

“I ran up the stairs, woke Thomas and shouted, ‘Our Peter’s shot! Our Peter’s shot!’ He at first thought my head was away. But he jumped up and ran downstairs. I knelt down on the floor to pray. I came down and they had all gone. I ran down to the hospital and I still noticed how beautiful it was. It was now getting bright. I ran into the RVH on the Grosvenor. There was police everywhere. I went up to one and said, ‘Could you tell me about the lad shot last night? I’m Peter Ward’s mammy.’ He sent me to a sister.

“‘Could you tell me about Peter Ward shot last night?’

“She looked at me. I said, ‘My Peter’s not dead!’

“She said, ‘Yes.’ I squealed the place down. Thomas heard me and came runnng. I shouted, ‘He’s dead! Peter’s dead!’ The priest and our Bell and her husband Seamus were coming in.

“Peter had been dead when the priest came to the house but he couldn’t tell me.

“That’s when the Troubles really started. You would never have heard of the IRA. Peter was dead and some of the other lads with him were wounded. After work in the International somebody said, ‘Let’s go for a drink.’ They went to the Malvern Arms on the Shankill. Gusty Spence had came up to my Peter and asked him where he worked and Peter said, ‘The International,’ not realising that it was mainly Catholics worked there. He didn’t want to stay in the pub. He was the first one out and the first one shot. He was shot once. It went straight through his heart.

“I never forget Peter. In my mind, everyday. I pray to him every night. To him – not for him. He was a good lad. Eighteen years old. Everybody liked him.

“Gusty Spence sent a message to me three years ago that he would like to meet me. I didn’t want to speak to him, then I said I would. He telephoned.

“‘You are Gusty Spence?’

“‘Yes,’ he said. He said he was sorry about what had happened.

“I said, ‘I’ll forgive you on one condition. That you do everything in your power for the peace of this country. Nobody should suffer the way I have suffered for I never forget my Peter.’”