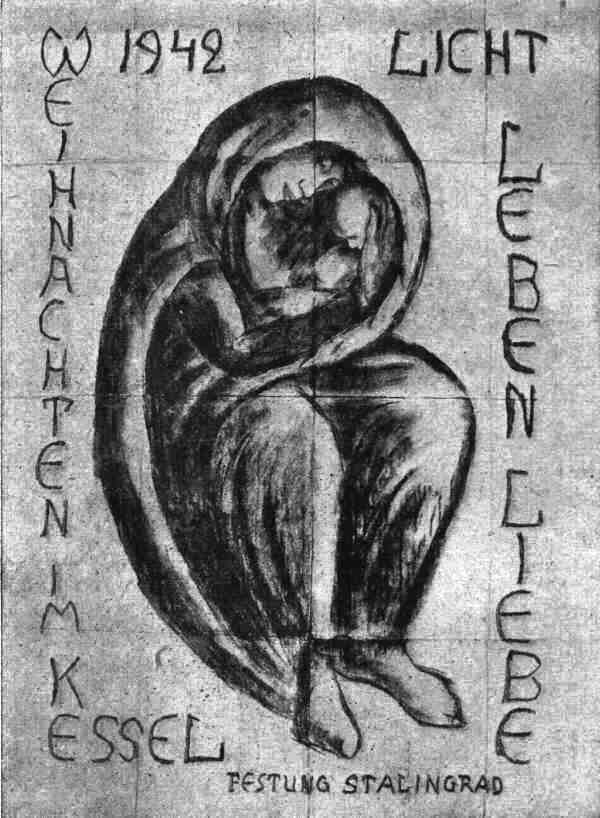

Dr Kurt Reuber was a pre-war Lutheran pastor but in 1942 was a Wehrmacht doctor in the 16th Panzer Division, tending the German wounded and dying in his dug-out in the steppe north-west of Stalingrad. Reuber was a gifted artist and to cheer up the wounded he drew a picture of the Madonna and Child on the back of a Russian military map as a Christmas decoration. When the drawing was finished, Reuber pinned it up in the bunker. Everyone who entered halted and stared. Many began to cry.

In a letter home Reuber wrote: “Christmas week has come and gone. It has been a week of watching and waiting, of deliberate resignation and confidence. The days were filled with the noise of battle and there were many wounded to be attended to. I wondered for a long while what I should paint, and, in the end, I decided on a Madonna, or mother and child. I have turned my hole in the frozen mud into a studio. The space is too small for me to be able to see the picture properly, so, I climbed on to a stool and looked down at it from above, to get the perspective right. Everything was repeatedly knocked over, and my pencils vanished into the mud. There is nothing to lean my big picture of the Madonna against, except a sloping, home-made table past which I can just manage to squeeze. There are no proper materials and I have used a Russian map for paper. But, I wish I could tell you how absorbed I have been painting my Madonna and how much it means to me.

“The picture looks like this… the mother’s head and the child’s lean toward each other and a large cloak enfolds them both. It is intended to symbolise ‘security’ and ‘mother love’. I remembered the words of St John: light, life, and love. What more could I add? I wanted to suggest these three things in the homely and common vision of a mother with her child and the security that they represent. When we opened the ‘Christmas Door’, as we used to do on other Christmases (only now it was the wooden door of our dug-out), my comrades stood spellbound and reverent, silent before the picture that hung on the clay wall. A lamp was burning on a board stuck into the clay beneath the picture. Our celebrations in the shelter were dominated by this picture, and it was with full hearts that my comrades read the words: light, life, and love.

“I spent Christmas evening with the other doctors and the sick. The Commanding Officer had presented the latter with his last bottle of Champagne. We raised our mugs and drank to those we love, but, before we had had a chance to taste the wine, we had to throw ourselves flat on the ground as a stick of bombs fell outside. I seized my doctor’s bag and ran to the scene of the explosions, where there were dead and wounded. My shelter with its lovely Christmas decorations became a dressing station. One of the dying men had been hit in the head and there was nothing more I could do for him. He had been with us at our celebration, and had only that moment left to go on duty, but, before he went, he had said: ‘I’ll finish the carol with first. O du Frohliche!’ A few moments later he was dead. There was plenty of hard and sad work to do in our Christmas shelter. It is late now, but, it is Christmas night still. [There is] so much sadness everywhere”.

The wording on the drawing is ‘1942 Christmas in the Pocket (literally, ‘Cauldron’), Fortress Stalingrad’ on the left, and ‘Light, Life, Love’ on the right. Dr Reuber died whilst in Russian captivity in 1944. His letter and the drawing were sent to his family, and they donated the artwork to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche (Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church), on the Kurfürstendamm in Berlin (the war-damaged structure still stands as a memorial to those who died in the conflict). The work, known as ‘Fortress Madonna’, is there to the present day, and copies were sent to the Anglican Coventry Cathedral in England and a Russian Orthodox parish in Volgograd (the current name for Stalingrad) in Russia as signs of post-war reconciliation between former enemies.