Ambush

Stevie arrived at the house first; he was always prompt. The others followed singly, through the back door, down the steps, through the small kitchen and tiny living room and up the stairs where they stunk out the back bedroomwith the constant smoking of cigarettes which steadied their nerves.

This call-house was new: a young husband and wife with republican sympathies had become active supporters about nine months before, converted by the violent excesses of the British after the introduction of internment. There had been many such converts, and even more following the shooting dead of thirteen civil rights’ marchers in Derry the previous January on a day soon known as Bloody Sunday. With quite a number of houses at their disposal, the unit changed call-houses every day, picking up the address from a trustworthy local shopkeeper. Those Volunteers on-the-run usually moved into the call-house during the early morning rush to school. Other good times for moving were at lunch-time and between half-three and half-five in the afternoons when the streets were busy again. Now, with the onset of school holidays, street routine had changed and moving about between operations could be as nerve-racking as actual active service.

Some Companies – those which were surviving the high rate of attrition through a mixture of shrewdness, recruitment and luck – were actually using two or three call-houses together.

In one a float could be in planning. On a float Volunteers in a car with one or two weapons would drive around – or ‘float about’ – until they found a British army target. Youths acting as scouts could be posted at street corners but often accidentally alerted the soldiers that something was afoot. It could be more dangerous than a set snipe in which an occupied house was usually commandeered and the Volunteers patiently waited for a patrol to turn up. But at least on a float they were always active and the operation – their day’s work – could be over and done with inside an hour.

Stevie, the Volunteers knew from loose talk, had actually gone out on floats by himself, without transport, and had once opened fire on two foot patrols using an AR 15 – an Armalite with a folding butt – which he had hidden inside a Marks and Spencer’s carrier bag.

In another house a bombing might be planned. In another the officer commanding the Company and his staff might be based. Co-ordination with other battalion units was vital as often three, four or five bombing units were going in and out of the city centre and criss-crossing each other. Where bombs were not planted in physical take-overs of premises but were left in car bombs or smuggled into shops, warnings had to be arranged.

Houses and local support – a base – were absolutely crucial to the continuation of the armed struggle. Some sympathisers were prepared to billet Volunteers, others would allow their homes to be used for meetings but not as a jump-off or run-back point for operations. Other supporters – the ones who commanded the greatest respect of the Volunteers – were prepared to hold weapons and explosives.

Contacts in the areas passed on the names of potential supporters who were then delicately approached and sounded out to see what use they could be put to – the demand for dumps always being the most pressing. As layer upon layer of support was built up, an extensive network came into existence; sympathetic houses, car owners, people in employment who passed on intelligence. The people became the eyes and ears of this people’s army and the word ‘sound’ when used to describe a supporter or another Volunteer took on a meaning more significant than the usual definition of reliable. Sound people could be absolutely depended on if the IRA was stuck; could be depended upon to give an objective opinion, to be truthful; could be depended upon if a Volunteer was in a tight corner.

‘Joe, open that bloody window, the smoke in here would kill you,’ said Stevie as he fanned his face.

There was a knock at the door. It was opened to the woman of the house who left in a tray of buttered baps and mugs of tea. The baby’s room had recently been decorated and carpeted. It had a Magic Roundabout lamp shade hanging from the ceiling and curtains patterned with scenes from a zoo. The clinical, Spartan smell of fresh paint was being coated in cloying, stale nicotine fumes.

‘Do you want an ash tray?’ she asked, a little bit anxious.

‘My apologies for these men,” Stevie replied. ‘They should be put out in the yard.’

She smiled back, acknowledging the concern. Her husband and she had a fastidious and proud attitude to their small home but she self-consciously mellowed when she thought about these lads and what they were facing. She returned shortly afterwards with ash trays.

‘By the way, I’m making a fry for Eddie later if any of you would like one. He’s to go to work at two, he’s on a shift.’

‘I’d love a fry,’ Stevie said. ‘I’m starvin’.’ He munched at his second bap.

When she left, Patsy let his envy be known.

‘How the hell could you eat a fry? I’m having trouble keeping down this tea.’ He had also been to the toilet twice and would me making more visits before the operation, though once they moved out and were actually on the go his equanimity would return. He knew this from his first three operations: throwing two nail bombs at soldiers on patrols and then driving on his first float.

‘Not only could I eat a fry, ma boy, but I could eat yours as well,’ answered Stevie, hungrily. ‘Anyway, down to biz. I’ve cleared a float with the double-O,’ he said, using IRA argot for Operations Officer. ‘If we don’t “touch” we have to wrap up before half-three.’

He made no reference to the explanation for the time limit but Joe knew that a car-load of explosives was due in the Falls around tea-time. Other Volunteers had been detailed to empty the door panels of the nitro-benzine mix and to dump it in sealed plastic bins under man-hole covers in a particular entry. The electric detonators gave off no tell-tale smell and were easily kept hidden in a house.

‘Joe, I’ll be on foot and youse float behind me. I’ll stay around the front of the road; we’ll “touch” quicker there. Tell Geraldine to take the thirty-eight and for her and Liam to take a car at the zebra crossing. They’re over in McDonough’s but they need to get another house to hold the driver. Hold his licence just in case he’s an Orangeman and bolts. Tell Geraldine not to be hijacking any women – they’ll only scream and things’ll be fucked up.’

Stevie pulled out various articles from the parcel he had asked Joe to bring.

‘Whadda you think of this?’

They all burst out laughing. He had pulled on an old cardigan and put on glasses with round metal frames which gave him a silly appearance. From beneath the bed he produced a borrowed pair of hedge-clippers. Finally, he dipped his comb in the tea and within seconds stood his hair on end.

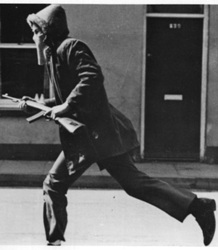

They admired the lengths to which he went. Some of the Volunteers experienced a thrill, unmasked, undisguised, running through the streets, armed. The Brits don’t wear masks, so why should fucking we, pride would foolishly dictate, as they left it to fate that ‘dead’ soldiers would never be able to ID them.

I see the patrol and I smile to myself. They haven’t been shot at in two weeks and they have relaxed. They have probably believed the bloody know-all intelligence officer in the barracks who put Gerry, Peter and Sean away in Long Kesh and thinks he has cleared out the unit. The second foot-patrol – their minds split between their profession and their home – is about five hundred yards behind, too far to be of tactical use in our maze of streets.

‘Joe, get the gear. Tell Patsy to put the car beside Murray’s house, facing up the street. We’ll get them from the corner against the hoardings.’

They stop outside the post office, the Englishmen, Scotsmen, Welshmen, the uniforms, I don’t give a fuck. One detains a woman shopper and rummages through her bag. I can make out her protesting, giving off, and, like a cat baring its fangs, some gland flushes a vengeance through me that tautens every muscle and sinew.

The radio-man stops a young lad. I can almost hear that jarring British accent ordering him to put his arms up higher and get them legs out. He’s feeling his jeans, frisking the body of the frightened kid.

Oh, I’m in control okay. I run my finger along cold steel. I stroke the smooth wood. Here they come, their sight of me bordering between curiosity and fear until I raise both hands and, with a clip, level the last section of the hedge. Like coagulating blood the juices rush to the white wounds. And the soldiers relax. I whistle The Rifles of the IRA, so cheekily, so contemptuous of their ignorance, with so much daring, almost challenging them, that it excites me and I am pleased with the aura of deception I have carefully fostered.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Here they come. They don’t see me even though they are looking directly at me. I look so happy and serene and domestic, standing with my hedge-clippers now tucked under the arm of my woolly cardigan. Greenfingers is hardly going to cut our heads off! No self-respecting English youth would be seen dead wearing that polka dot shirt, fastened by that kite-sized tie! And because I am a twenty-year-old gawk, and bespectacled (with clear glass), and because this is a strange land, because this is Ireland, I know they shrug me off. Innocence oozes out of me. The leader of the patrol does not mentally mark me down to be p-checked. He comes up to me, me with the clownish grin, specky four-eyes, and I use our exchange of glances to impart a duplicitous trust and friendship. I have that brotherly respect for both of us that opposing combatants share in war, but I cannot confide in him in the way that his battle fatigues mark him out for me. Fraternisation, communication, pity, restraint, humour, is always their gift, depending on their mood, depending on what side of the bed they crawled out. Favourable responses, replies, repartee, and their eyes sparkle as if they’ve just seen light at the end of the tunnel. But these are never sentimental exchanges across no man’s land. There’s no football at the Christmas front. The Brits remain implacable and we cling to our cunning.

As he now passes me, me whom he’ll never see again, I turn into the side-street of my youth and run across a few feet of cobblestones before the tarmac takes over. From here I can almost touch the house I was born in and the entry where standing in darkness we fumbled at first making love.

I stop my mind and note that in these few seconds of running, a thousand reflections, experiences, mixed feelings and considerations, and a few specks of golden wisdom panned over twenty years of my life, have gushed through my muddy consciousness.

I move as natural as this sunny afternoon’s light breeze across the Falls Road, an imperceptible shift of air that would hardly tickle a fly. I am honed for the delivery of this stroke like the finely pointed lead of a sharpened charcoal pencil between the fingers of an artist. I am immortal: I shall see tomorrow. This will be that corporal’s last day.

I think of this man. He is somebody’s son, perhaps a good man, maybe even a loving husband. We both speak the same language, could have stolen the same bars of chocolate from the corner shop, told the same juvenile jokes to our mates, and sheltered from the same storms as they fell a few hours apart on our lands. I came up on the same music and television as he did, the Beatles and Coronation Street. But the British public – his ma and da, their governments – didn’t even know we existed and cared nothing. When I pieced things together for myself, when I listened and watched, I understood it all – the police batons, the house-burnings, and then my decision to fight back. Sitting with the patience of a prophecy was my Irishness, waiting to be tapped and to explode.

He probably doesn’t even want to be here.

Already I can hear the familiar sermon echoing all the comparisons and lecturing me, the killer. I can see those comparisons myself right down to our mutual likes and dislikes in food, Granny Smith’s apples, flowing butter on warm white bread, plenty of salt and vinegar on the fish and chips.

We may even have supported the same team for the FA Cup.

He probably doesn’t even want to be here.

Everything can conspire to scream at you, to weaken your resolve. Everything I’ve been taught, from the words of my mother, to my schooling, my religious teachings, my own beliefs, were all part of a moral system whose effects are to cripple this action and deter me. Then there is the smug power of the status quo and the awesomeness of existing authority.

My own body’s bowels could burst as a signal of cowardice, a warning of the danger, a call to self-preservation. A twinge of conscience, yesterday’s bloodshed, can become a black nightmare. (I have seen that in comrades who fell away ‘because of the wife’, because they found an ideological difference or used personality clashes as a pretext. In others it was the ghosts who broke their health or minds, or they had a flawed commitment to begin with.)

He probably doesn’t even want to be here, but he is!

And that’s my edge over him, over all their arguments. That’s why I have blood like oil lubricating my calves and thighs, my buoyant steps, which take me through these close streets and into Murray’s street, ahead of the Brits.

He has no right to be here and if doesn’t want to be here then he shouldn’t be here. He can kid himself, and may well have done so, but when all is said and done here he comes, sauntering up my road with his gun in his hand, doling out his mood to pedestrians, ever nosey and curious, ever the law, on top, dashing for his survival across open spaces because he knows we don’t want him. He would just as quickly rob me of breath if ordered or if the fancy took him. But I am just too smart for the poor bugger. Governments may have us, the foot soldiers, at each other’s throats but I am a soldier and a general, a politician and a civilian. I am my own government, but without him there is no government, no British rule.

I am not claiming the certainty of God’s blessing for my actions. I am not that conceited. I believe in a God. I see the beauty of God’s creation all around me, especially in this man with the clean face and short hair who’ll never shave again, in the red roses over there bathing in the floating warm air, in this demonstration of power and fate unfolding and the tragedy of trapped people. My conscience reminded – not beset – by the occasional doubt is also a remarkable process which keeps me right. I entertain doubts precisely because they strengthen my single-mindedness, my convictions. The fact that I am doing this in spite of myself, against the grain, against my nature, and not because they ever killed anyone belonging to me but because I have rationalised this confrontation and carry it out on behalf of others, proves that it isn’t personal revenge. I take up a gun for every arthritic Irish man who fucks the English up and down (and not really the English but these Brits and their system). I am here on behalf of all those too weak to retaliate or who lack the stomach for violence or lack the courage to risk their own lives.

I am the history maker. This is my power, this is my cause, and behind me lie centuries and centuries and a thousand lands where similar foreign fuckers with rifles or bayonets, not ever wanting to be here or there, were around just the same, doing their missionary work, civilising us natives, maintaining their peace.

Oh, they have their doings well sewn-up, well wrapped in a law and a morality whose smartness only the likes of me can really smile at and appreciate, because I am an arsonist with their property and institutions and I know the thief below the bow and wrapping paper.

Yes, the God thing and thou shalt not kill. It’s even harder for us. The Brits were suckled on superciliousness, on empire building, that others were Coons and Paddies and bloody Kaffirs.

The pulpits say I’m for hell! We were reared to conform, not to kick, so it doesn’t come easy to copy the killers and kill and even-up history a bit. I’ll even stretch my imagination and allow that a Brit can be a relatively innocent being. So I snuff out an innocent life and – bingo! –he goes straight to heaven. I’ve done him a favour, before he committed any serious transgressions and sentenced himself to eternal damnation. On the other hand, if he’s a bastard and was heading for hell anyway the most I’ve done is put him there prematurely. So where’s the sin?

I’m being silly.

I’m not as callous as this and there’s always, always, always, a psychological unease, a sense of violation and wrong, about killing this man, or the other three soldiers I shot and blew up. Experiences and intellect, the slide into violence, eliminate the compunctions and Time absorbs the inhumanity. If I go to hell for this, I’ll go to hell. My soul will burn eternally not for something I did only for myself but for what I did for others. And God’s not up to much, if he’d burn anyone forever and ever. Imagine having those screams on your conscience!

I pass the garden shears back to one of our supporters, an old man who sits on a chair at his front door reading the Irish News.

‘Good luck and be careful,’ he says solemnly.

‘The Gardens are clear,’ Joe shouts to me. ‘So is the Drive and the Road.’ Wearing gloves he opens the boot of the Cortina.

‘Wait a minute,’ I order. He snaps it shut. I walk out to the corner for a last look. I am on stage. The cobalt blue sky, the blazing sun focus on me, the main character, me with the magic fore-finger, fate-maker, sorter-out of British soldiers come to do you harm.

‘Quickly, they’ve stopped some fellahs again.’ But as I turn I see two armoured cars come down the Falls Road.

‘Wait!’

They whine. They trundle past, bleeping their hooters to their friends who wave back. The air is pungent with the foreign smell of their exhaust fumes. It all becomes so real, so critical, so deliberate.

My comrade opens the boot again. I put on my gloves, place the silly spectacles in a side pocket of my corduroy trousers, pull on a cap, and lift the Garand rifle which I prepared myself earlier. Patsy, our driver, turns over the engine and I note his nervousness. Joe takes up a position with an Armalite to cover my back. The area is not too busy. Traffic is light. Two big lusty mongrels bare their teeth and slabber at each other as they canter after a blonde little poodle whose self-importance rises with each sniff and growl from the competitors.

I peep around the corner. We used to sit here when school was over and play cards and whistle after the girls from St Louise’s – the ‘brown bombers’ we called them. Little did we know the use of corners.

Mr Corporal is just about one hundred yards from me, down on his hunkers, finishing the frisking of a young lad. A colleague holds his weapon. Another soldier leaning over a wall and pointing his SLR directly at me, concerns me, but I am gone from sight and I have made him doubtful I think by the time, a few seconds later, when I re-appear with my raised rifle, the butt resting comfortably into my shoulder, into my spine, down to my firm feet, like it’s a part of me.

And it is now that I make my thunderous finale. The corporal’s back collapses inwards under the severe punch from a bolt of lightning lead but I too feel an unusual recoil as the top furniture of my rifle is splintered by the shots returned from the alert marksman.

We turn and run, Joe firing a burst into the air which keeps the Brits pinned down under fake fire. It’s a good excuse for some of the yellow bastards to stay put. A woman has fainted but some kids start cheering and clapping our performance. The weapons are thrown into the boot and my two comrades, as arranged, drive off; Joe to hand over the weapons to the quartermaster; Patsy to dump the hijacked car in the Kashmir district where Volunteers from another unit are waiting to use it as a lure in an ambush. I run into side streets, air streaming across my brow, blowing through my hair, curving my body. I run up an entry where a stout woman, her grey curls loosely pinned around a falling bun, is brushing some rubbish from her back door. ‘Jesus Christ, what was that son?’

‘I don’t know missus, but I think somebody opened up on the Brits.’

She blesses herself and rolls her eyes. I cross into another entry and push open a back door. My clothes I put into the washing-machine. I switch on the thermostat, though the water is still warm, and turn on the motor of the twin-tub. I like this house because it also has a shower.

As I climb into its spray I can hear the engines of armoured personnel carriers, of landrovers.

They don’t even know where to begin.

Pellets of water pummel my face.

I hear on the news that the corporal is dead, that he was married with two children, aged four and one. I clench my teeth and swallow hard and I will often think of this man.

I curse the life that has brought me to this; then I focus in on the British government. I think of the corporal who might have hated his job, who might have been buying himself out of the army.

I’ll live for him and in some sort of communion with him.

One thing is for sure.

I’ll think about him more often than his commanding officer.

I’ll maybe even be still thinking about him when his widow has stopped.

Who knows.