In 1970, within months of the conflict breaking out here, two books, long in gestation, were published: The IRA by Tim Pat Coogan; and The Secret Army by James Bowyer Bell.

I remember speaking to several veteran republicans who had been interviewed and who defended themselves against criticism and begrudgery from those veterans who had refused to be interviewed. Invariably, the interviewees claimed to have been misquoted or had been taken out of context or hadn’t said what was attributed to them.

Nevertheless, for teenagers (and others) like myself, the books revealed in great detail the operation of an underground army, the comradeship that bound it together, and the clashes of personalities and differences over principles, decisions and strategies that often threatened to rent it asunder (and sometimes did).

I felt that most of the IRA men and women written about were elevated and were probably proud to have their sacrifices and resistance recorded for posterity, even if others disputed their precise role or part.

One thing was for sure: the books were published at a time when prosecutions had closed. No one would suffer arrest and imprisonment – unlike the debacle of Boston College’s Belfast Project which has resulted in the arrest and charging of an 81-year-old republican and a 67-year-old loyalist with historic offences.

Aaron Edwards

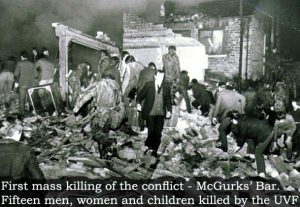

I’ve had Aaron Edwards’ book, UVF – Behind The Mask, for over a year, began reading it, and put it down several times because the accounts of one sectarian killing after another are unremitting, bleak and depressing: McGurk’s Bar, Dublin-Monaghan bombings, the Shankill Butchers, Billy Wright and the breakaway LVF.

I also wondered how I’d feel as a loyalist, who had either agreed or refused to be interviewed, and whether I thought the book contributed to my cause – or my ego in the case of participants, in explaining my part, and putting ‘the record’ straight. When in 2014 the late William ‘Plum’ Smith’s book, Inside Man – Loyalists of Long Kesh, was published many of his erstwhile comrades ridiculed the accuracy of it or questioned how central he was to this or that development.

You can see the territory which Edwards – who was born in Newtownabbey but now lectures at Sandhurst – has entered. In one sense, it is a book not without risk or contention, given that he and his family hail from a loyalist area. Of course, that might also explain the trust placed in him and his access to leadership figures. There can be a fine line between explaining and defending and although there is a subconscious sympathy (between the lines) with some loyalist figures I don’t think Edwards ever becomes an apologist. He is also of the view that what marks the UVF out from its rivals in the UDA is that it is more disciplined and coherent – though all that is relative.

Edwards also promulgates that theory searching for a good home and much professed in the book, Secret Victory, by former RUC Special Branch officer William Matchett that the IRA was defeated and the RUC won. Yes, that would explain why the RUC is no longer, and why Matchett’s new ‘beat’ is the corridors of Maynooth College where he now lectures. It will come as no surprise to the families of victims of state violence that Matchett is of the view that “what we had was the most human rights compliant security response to any conflict before or since.” The tone of that sentence alone explains just how self-delusional he is.

Loyalist paramilitaries also initially claimed ‘victory’ in August 1994 when the IRA cease fired. They claimed that it was brought about by their intensive killings in the 1990s. I can understand why loyalists would want to believe that – it gave perverse meaning to their ‘dirty, stinking, little war’ (David Ervine) – but I’ve yet to meet a republican (and I’ve met quite a few) who was swayed towards the cease fire because of the loyalist campaign. Other factors were to the fore.

The passage of time and experience has chastened many loyalists of that 1994 boast, though some still express it in UVF – Behind The Mask. But Edwards also quotes the daughter of assassinated UVF leader John Bingham, Liz Bingham, in 2012 during the flag protest: “We were promised that the Good Friday Agreement would change things, and make the union safer. Instead it has never been more unstable for the Protestant community.”

(The book was written before the full implications of Brexit could be appreciated and which is changing the political dynamic here.)

It was a friend of Edwards, the older William ‘Billy’ Mitchell, and very much a mentor to Edwards, who suggested he write a ‘warts and all’ book about the UVF. In many respects, the book is a paean to Mitchell – the killer-turned-peacemaker – who died in July 2006. I once spoke on the same platform with Mitchell in East Belfast and was impressed by his humility and honesty.

Mitchell was one of the founders, along with Gusty Spence in 1965, of the modern UVF (many of them ex-servicemen and members of the Orange Order) which to justify its existence imagined an IRA conspiracy.

Ten years later, 1975, Mitchell was imprisoned for abducting, killing and disappearing not two IRA men but two UDA rivals during a feud: Hugh McVeigh, aged thirty six, and David Douglas, aged twenty. Their bodies were later recovered in a shallow grave in Islandmagee.

The nexus between mainstream unionism and loyalist paramilitaries is stark at times of heightened emotion. It can be seen in the use of militaristic rhetoric and symbolism by politicians such as William Craig in his fascistic cavalcades in 1972 or Paisley with faux gravitas donning his red beret in the Ulster Hall.

The case of Lindsay Robb, UVF, is quite illustrative. In June 1995 Robb was part of the PUP talks’ team. But two months later he was arrested in Scotland and charged with arms smuggling. A meeting protesting his arrest was held in Carleton Street Orange Hall and was addressed by Sammy Wilson who said he was proud to be among the people of Portadown to celebrate the victory of Drumcree (when the RUC forced an Orange march through Garvaghy Road against the wishes of the residents).

“‘People like Lindsay Robb played a part in that victory. All too often in our history. Some of them had given up their freedoms. Many had lost their livelihoods for the cause,’ said Wilson. ‘And far too often, many of those who have benefited from those sacrifices, have turned their back on the people. I want to tell you that I am proud to be associated with the people who made the sacrifices.’”

What guff.

As long as loyalists are seduced by such false camaraderie – despite the number of times they have been used, demonised, rejected, then re-used again, and keep going back for more – they are, politically, going nowhere. They may well even have missed the boat.

To go back. Edwards writes that some of the founding fathers, “later admitted that the UVF was really a tool of political intrigue utilised by a handful of faceless right-wing unionist politicians,” and “that it was part of a wider conspiracy to oppose [Terence] O’Neill’s liberal unionist agenda.”

For the record, Prime Minister Terence O’Neill’s offence was to meet An Taoiseach Sean Lemass in 1965 to do no more than improve cross-border relations.

O’Neill wasn’t an ecumenist but a proselytiser. This was his attitude towards one-third of the population, the nationalists:

“It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give Roman Catholics a good job and a good house they will live like Protestants because they will see neighbours with cars and television sets; they will refuse to have eighteen children.

“But if a Roman Catholic is jobless, and lives in the most ghastly hovel, he will rear eighteen children on National Assistance. If you treat Roman Catholics with due consideration and kindness, they will live like Protestants in spite of the authoritative nature of their Church.”

Some of the politicians – now all dead – linked to the new UVF were James Kilfedder, Dessie Boal and Johnny McQuade. I’m sure there were others. Others in the Ulster Unionist Party who are still alive. Who are they? A hint would do. Alas, Edwards’ lips are sealed.

Billy Mitchell admitted coming under the spell of the Reverend Ian Paisley. Hugh McClean, when arrested in 1966, charged with murdering young Catholic Peter Ward, said: “I am terribly sorry I ever heard of that man Paisley or decided to follow him…” The late David Ervine also criticised senior unionist politicians who had secretly conspired with the UVF while publicly condemning them.

“I sat there with them,” he said. “I could tell you the colour of their wallpaper.”

Gusty Spence’s philosophy was: “If you can’t get an IRA man, get a Taig.”

In 1969 the IRA was blamed for bomb attacks on key installations which were actually the work of the UVF. It is doubtful if the IRA, prior to 1970, had the ability, the inclination, the will or the motivation to bomb power stations or reservoirs. All that would come later.

Loyalist paramilitaries routinely claimed that their existence was solely to counter the IRA, that they were ‘counter-terrorists’, and their attacks were in response to the IRA. Edwards correctly contradicts this and states that the UVF was formed as “a political tool for right-wing unionism… and not, primarily, as a blunt instrument to destroy the IRA.”

However, it was to become a blunt instrument. The graph of loyalist paramilitary violence shows that its activities against nationalists (as distinct from its corrupt activities against its own community) were proportional to their perception of nationalist gain or advance.

Thus, the shooting of John Scullion and Peter Ward, a year after the Lemass meeting; the bombings to bring down the ‘too liberal’ O’Neill in 1969; the intensification of sectarian killings in July 1972 during the IRA truce; the unification of the UUP, DUP, UDA and UVF under the umbrella of the Ulster Workers Council which brought down power-sharing in 1974; the DUP/UFF second strike in 1977; and the various incarnations of a Third Force, Ulster Clubs, Ulster Resistance etc.; and the Glenanne Gang’s specific targeting of Catholic business people with no republican links. All designed to terrorise all shades of nationalists and force them to accept their lot.

Down the years loyalists were able to raid barracks for arms because they had inside help. They also received information from state forces, and in the late 1980s (when the IRA had been heavily re-armed via Libyan shipments) this collusion appears to have become more streamlined. Tellingly, one UVF leader says: “See by ’89 [it] all changed. And the intelligence started swamping. The leakage from security forces was phenomenal.”

Edwards writes: “the UVF had just taken possession of high-grade intelligence from disgruntled members of the Security Forces … the dossier detailed the movements of known IRA players, their girlfriends, wives, brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts and known associates.”

Of course, the organisation was also heavily infiltrated: the most recent example being that of serial-killer Gary Hegarty, former UVF commander for North Belfast, who was a paid police informer for eleven years and who turned ‘supergrass’ in 2009.

Edwards deals in considerable detail with the UVF’s repeated attempts to enter mainstream politics. I have to say, if I have read once about how the paramilitaries were betrayed by the politicians they had played puppet to, I have read it a thousand times, and the only conclusion one can reach is that they are so psychologically in thrall to sectarian group thinking that they will never break away.

Here we are in the mid-70s. The Long Kesh cages. Spence has come a long way from his early philosophy: “The development of a class-based unionism,” says Edwards, “would become increasingly important once the political thinking seeped out of the [Long Kesh] compounds, to those key people in the non-combatant ranks of the UVF.”

More: “Believing themselves to have been encouraged to take up arms, compound men began to question what had driven them to take the law into their own hands in the first place.”

Billy Mitchell, himself, believed that “he had helped create a monster.” In 1979 he became a born-again Christian, gave up his political status and moved to the H-Blocks to serve the rest of his sentence. Upon release in 1990 he decided to do community work: “to champion the cause of the most marginalised and disadvantaged members of the wider community.”

Mitchell, years later, again identified the problem for working-class loyalism: “…there was a realisation that middle-class … unionists hadn’t served us well, in terms of social policy or economics. There was also a realisation that most of our political philosophy was summed up in clichés. ‘Not an inch’, ‘no surrender’, ‘what we have we hold’. So, there were two strands of thought. One, we realised that we hadn’t been served well and we needed to develop our own leadership, we needed to take ownership of our own communities.”

It’s hard to believe that the PUP was founded in 1979. It even contested elections before Sinn Féin developed its electoral strategy after Bobby Sands’ victory in Fermanagh and South Tyrone. In the May 1981 local government elections the PUP got 3,000 votes. In the assembly elections that followed the Good Friday Agreement it polled 20,634 votes and saw David Ervine and Billy Hutchinson elected.

But its success has been bedevilled by the inability to progress because of several factors. Firstly, the UVF is still active, despite claiming to have decommissioned. Why would any community, even if it sympathised with you for having suffered imprisonment, vote for you while you are either involved in extortion, drug-pushing and criminality, or, you can’t distance yourself from it, or you won’t distance yourself from it?

When it lost David Ervine, who died in 2007, it lost its way. Progressive voices have been side-lined and driven out. People like Dawn Purvis, who could no longer tolerate the contradictions, and Sophie Long who was driven out of the party because she tweeted, “condolences to Martin McGuinness’ family, friends and comrades”.

So, the PUP, despite all its rhetoric, is still tied to the apron strings of the mainstream unionist parties.

When Sinn Féin decided to contest the June 1983 Westminster elections I was the candidate in Mid-Ulster. In the Ulster Herald the SDLP’s Denis Haughey accused me of splitting the vote and letting in the DUP’s William McCrea. The argument had some resonance. In the 1982 Assembly elections the SDLP were the larger party and had polled 15,444 votes to our 12,690. Only a single nationalist candidate could defeat McCrea.

But our purpose was to build a political party and in the process, hopefully, take the seat. As it turned out, in June 1983 we now outpolled the SDLP (16,096 to its 12,044) but McCrea beat me by 78 votes and was ensconced as the MP for the next fourteen years. Yes, the nationalist vote was split, the seat was lost, we took some flak, but we had built a party and in 1997 Martin McGuinness ousted McCrea. Today, Sinn Féin is the party chosen by the nationalist community to represent it.

But look at North Belfast where last year the PUP’s Billy Hutchinson stood aside in case his candidacy would hurt the DUP’s Nigel Dodds. The PUP was more interested in sectarian solidarity and afraid of being accused of allowing John Finucane to be elected than it was of distinguishing itself from the DUP.

And that is why it will never break through.

Today, the UVF remains active and has recruited many young people – ‘ceasefire soldiers’ – who, ipso facto, require things to do. Local reports, observers, the media, the PSNI, all state that the organisation is still engaged in drug-dealing, extortion, threats and intimidation, punishment beatings and shootings.

Unfortunately, for working class unionist communities, the UVF is still ‘behind the mask’. And how to deflect from a scrutiny of its activities? Run up flags. Pile up pallets. Beat the drum.