Antony Beevor has a knack of making history really accessible. Before I came to his books, I had read serious and light literature about the French and Russian revolutions, the First World War and the Vietnam War, etc. I have also interviewed protagonists (for example, General Otelo de Carvalho who led the Portuguese Movement of Armed Forces in the Carnation Revolution which overthrew Caetano, the fascist dictator) but regardless of my admiration of courage/bravery, deep down inside I have always been averse to war or conflict. Yet that is a major contradiction because I also understand the necessity of ruthlessness.

I hate descriptions of battles and the details of the ordnance, the shells, the detonators, and this tank and that rocket, and how well we did only to lose 100,000 soldiers, etc. Having said that, I do vaguely recall reading ‘War And Peace’ in Cage 2, Long Kesh, in 1973, lent to me by Ted Howell, and being impressed by Kutuzov who commanded the Russians against Napoleon in 1812 at the Battle of Austerlitz [I think!].

But in ‘Berlin’, we discover, for example, that one army alone, the 1st Belorussian Front, had a stockpile of over seven million shells, of which 1,236,000 rounds were fired on the first day of the offensive! 1,236,000 shells fired in one day!

I read Beevor’s ‘The Siege of Stalingrad’ last year and was mightily impressed. So, here are my observations on ‘Berlin’.

To quote him: “Many Soviet troops, especially the frontline formations, unlike those who came behind, often behaved with great kindness to German civilians. In a world of cruelty and horror where any conception of humanity had almost been destroyed by ideology, just a few acts of often unexpected kindness and self-sacrifice lighten what would otherwise be an unbearable story.”

I actually use a similar theme in my unpublished novel ‘Rudi’: “The stories that attracted Rudi were not the success of great battles or even the contentious triumph of alleged good over alleged evil but those accounts of individuals acting against the tribe, against the rules: the soldier who allowed a prisoner facing execution to escape; the SS man who risked his own life by warning a Jewish former school pal that Jews were being murdered in the camps and that he should flee. Such acts might not alter the course of history but they did ennoble mankind a little.”

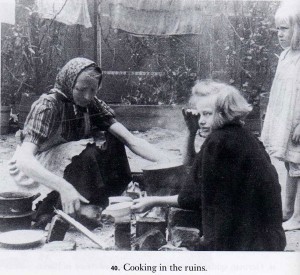

I had read before, but never in such detail about the Soviet victory over Germany being sullied by the mass raping of the young, the middle-aged and the elderly. Even Russian women and girls, who had been seized for slave labour by the Reich, were, upon liberation, then subjected to major sexual assaults by their own countrymen that, in a way, would make one despair about how little we are removed from beasts (though beasts would probably be more kind).

I read such books as Beevor’s also for an appreciation of how people survived, how ran the emotions, how love survived.

Beevor quotes Vasily Grossman’s novel ‘Life And Fate’ (another that I must read before I die): “The extreme violence of totalitarian systems proved able to paralyse the human spirit throughout whole continents.”

On the eve of the attack on Berlin the Berlin Philharmonic gave its last performance, playing, despite the electricity cuts, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, Bruckner’s 8th Symphony and, appropriately, the finale to Wagner’s Götterdämmerung!

Meantime, the Russian soldiers listened to a song fashioned to the haunting melody of Zemlyanka; ‘Wait For Me’, based on the 1942 poem by Konstantin Simonov; and ‘Blue Shawl’, about a faithful girl’s farewell to her soldier lover… who might well have perished.

Currently, I am reading Hans Falluda’s ‘Little Man, What Now’, published in 1932, the year before Hitler came to power, and I am not sure where it is going, but the main female character, Lammchen, is very naïve, and I doubt if she will turn out to be a fascist. I hope she doesn’t.