Guest writer Roy Greenslade reviews Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire by Caroline Elkins.

-oo0oo-

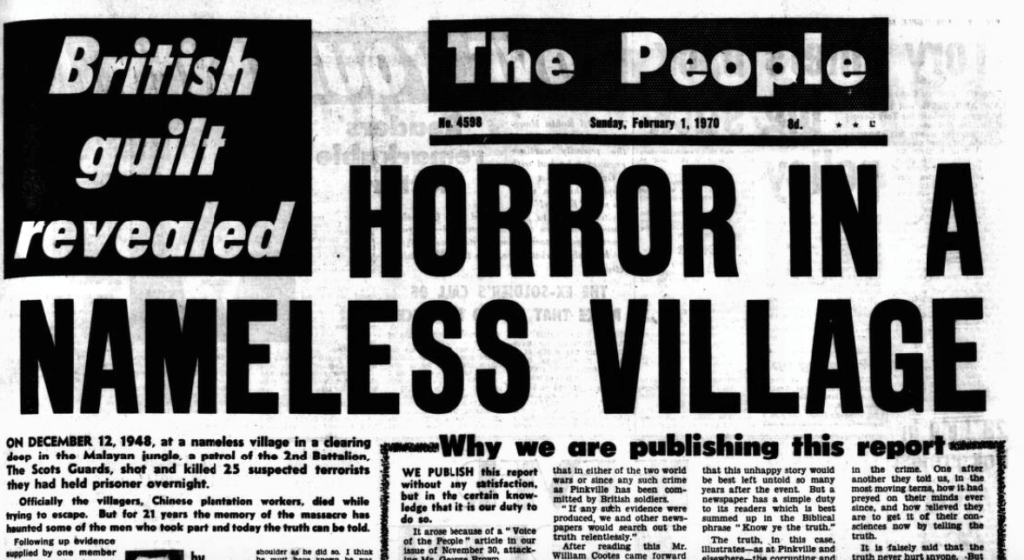

In 1970, a popular British newspaper published a story that rightly deserved to be called sensational. The People reported that British soldiers had massacred twenty-four innocent, unarmed villagers in Batang Kali, Malaya, in December 1948, at the beginning of what proved to be a twelve-year struggle by Malayans to liberate themselves from the British Empire.

The newspaper’s evidence was irrefutable because it was based on the testimonies of five men, former members of the Scots Guards regiment, who had been responsible for perpetrating mass murder. Four of them confessed, under oath, to the killings.

For a variety of reasons, the revelation was unique. It was a significant departure from The People’s largely trivial agenda. It was bound to attract government and military hostility. It risked alienating a large segment of its fifteen million readers. Indeed, several senior staff were opposed to publication, warning the editor, Bob Edwards, that sales were bound to nosedive. In fact, few, if any, readers deserted.

There were certainly letters of complaint, some of which the paper published, and the views they expressed were predictably defensive of the troops. One said: ‘I ask you to refrain from humiliating the British Army any further in full view of the world.’ A former member of a Guards regiment wrote: ‘These Guardsmen were there to do a job… Let us not question what happened, how and why… Let it be forgotten.’ Another ex-Guardsman excused the war crime on the grounds that ‘atrocities happen frequently in war and are committed by all parties.’

What was not unique was the response by the rest of the British press and the establishment. Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe dismissed the story as ‘trial by newspaper.’ A headline in The Times summed up the official reaction: ‘British troops made a “bona fide mistake”’. No newspaper sided with The People, which was regarded as lightweight and, as such, could be safely ignored.

With little pressure on the government to institute an inquiry, it passed the buck to the Director of Public Prosecutions who side-stepped the issue by deciding that a lack of documentation made it impossible to verify the veracity of the men’s testimonies.

In subsequent years, demands for inquiries—including petitions to the Queen in 1993 and 2004—were batted away on the grounds of insufficient evidence. Legal actions led nowhere. In a remarkable High Court ruling in 2012, judges acknowledged that Britain was responsible for the ‘deliberate execution of the 24 civilians at Batang Kali’ yet upheld a government decision not to hold a public hearing.

Three years later, the Supreme Court, also conceding that Britain may have been guilty of a war crime, decided the government was not obliged to hold a public inquiry because it had occurred too long ago. Malaya went on being misrepresented as a ‘model’ of counter-insurgency.

If this atrocity, ensuing cover-up, and persistent official denial of the truth were an isolated incident, it would be appalling enough. But this was just one among hundreds of examples of murder and deceit committed by Britain in its imperial pomp. And, lest we forget, it was exactly what happened in the colony it calls Northern Ireland on, and after, 30 January 1972 in Derry: mass murder, whitewash, official cover-up, lies, and a thirty-eight-year struggle before the government formally apologised for ‘indefensible’ action by its troops (none of whom have yet been convicted).

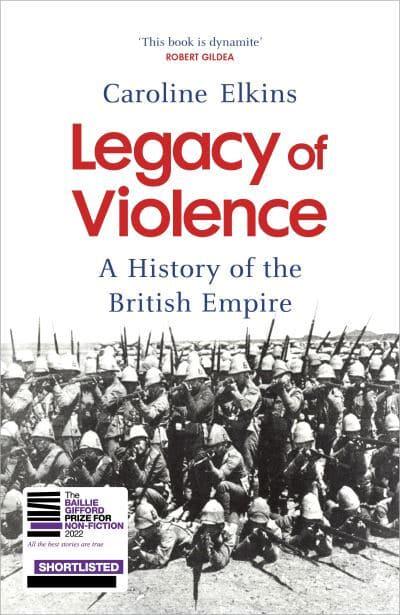

What happened on Bloody Sunday and at Batang Kali were not aberrations. These actions flowed naturally and logically from imperial policy and philosophy, as Professor Caroline Elkins convincingly argues in her devastating book, Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire.

She illustrates how British power was maintained in all of its colonies across the globe by the exercise of extreme violence—including indiscriminate murder and horrific torture—on the basis that the ends justified the means.

Under its imperial ethos, ‘backward’ people were to be transformed by the enforced importation of an economy based on free trade, (Anglo-Victorian) forms of social relationships and a new system of law and order. To achieve these changes, British politicians, their bureaucrats and their military enforcers applied classic liberalism, as preached by John Stuart Mill, who saw nothing wrong in advocating the advantages of ‘paternal despotism’.

The key to ensuring that colonised peoples were cowed into obedience was the complementary implementation of the gun and the law. Elkins rightly calls this ‘legalized lawlessness’, which the arch imperialist, Winston Churchill, euphemistically called ‘lawful authority’. Under its aegis, people were to be ‘civilized’ through military barbarity and judicial severity (applying, incidentally, laws enacted ‘democratically’ in faraway London).

Elkins demonstrates how this exercise in ‘liberal imperialism’ was a ‘mechanism for imposing Western values on peculiar populations with their strange cultures and different skin colours.’ She does so through a forensic examination of how Britain acted during, among others, the Boer War, the uprisings in India, Kenya, Iraq, Palestine, and the Irish War of independence (where a certain religious persuasion replaced skin colour as the defining characteristic of otherness).

But this portrait of empire was not what I, as an English schoolboy in the 1950s, was persuaded to believe. Our classroom wall was decorated with a giant map of the world in which the most noticeable feature was the number of countries coloured pink, the territories and dominions ascribed as being under British hegemony.

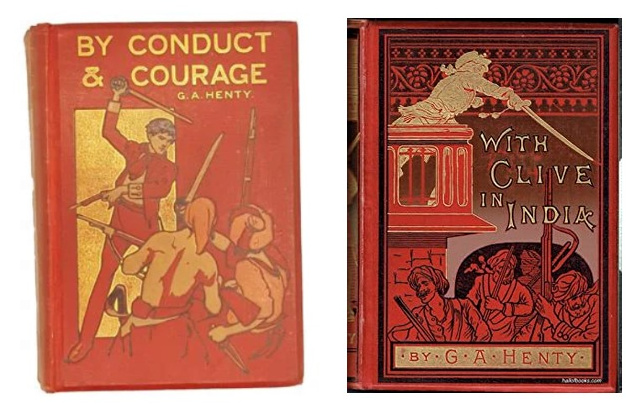

Along with my contemporaries, I happily recited the poems of Rudyard Kipling, read the novels of G.A. Henty and saluted the founder of the Boy Scout movement, Baden Powell. These imperial ideologists promoted an image of a benign and enlightened British Empire, a doctrine as potent during my youth, a period of imperial disintegration, as it was during its zenith. Plenty of historians have since continued to view it in those terms.

Along with my contemporaries, I happily recited the poems of Rudyard Kipling, read the novels of G.A. Henty and saluted the founder of the Boy Scout movement, Baden Powell. These imperial ideologists promoted an image of a benign and enlightened British Empire, a doctrine as potent during my youth, a period of imperial disintegration, as it was during its zenith. Plenty of historians have since continued to view it in those terms.

So pervasive was this indoctrination, with its underlying messages of British exceptionalism and cultural superiority, that we bought into the whole package. Unlike the savages they claimed to be taming and civilizing, ‘our boys’ were imbued with a sense of fair play. War crimes were committed against us, never by us.

Elkins’s formidable research, based in part on previously secret documents squirrelled away in a high-security government facility in Buckinghamshire, Hanslope Park, put a lie to such illusions. Her sustained polemic, which relies entirely on facts, all carefully referenced, reveals disturbing and uncomfortable truths.

For example, some of the passages about the use of torture, particularly the forms employed in Kenya, are gruesome to read. But it is important that she has recorded exactly what happened. For the devil, in every sense of that phrase, is in the detail. And it is to her credit, and to our benefit, that she has written such a penetrating account of Britain’s perfidious imperial endeavour.