At times, reading this brilliantly researched and brilliantly presented story is like revisiting the prison protests in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and Armagh Gaol, so startling are the parallels. What, of course, it does prove is that the British, well-versed and rooted in their colonial history, particularly the civil service and the prison administrations, knew exactly what they were doing in 1976 when they withdrew political status.

History told them that republicans would resist criminalisation.

They knew there would be prison protests.

They knew there would be hunger strikes.

They knew, again from history, that the prisoners would not submit, even as they faced inevitable death.

Yet, the British went ahead anyway with their doomed programme, which means they were either incredibly stupid (thinking that this time things might turn out differently) or incredibly vindictive; or both.

In this book Tomás Mac Conmara digs deep down into history, down to the roots, and uses a considerable number of sources to bring alive the major contributions to the struggle for independence from just one county, a county which had a proud tradition of rebellion from 1798 on.

It is an incredible story revealing things I was not aware of. For example, I always believed that the Tan War/War of Independence was dated from and was inaugurated by the fatal shootings of two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) men at Soloheadbeg on 19th January, 1919, on the day that the First Dail sat in session in Dublin, an attack which was not sanctioned by GHQ but was somehow retrospectively legitimised by Sinn Féin’s TDs.

Instead we learn that ten months earlier Clare republicans opened fire on the RIC, killing two constables outside Ennistymon. And that even before that, IRB member John Joe ‘Tosser’ Neylon laid claim to be the first republican to fire on the police since the Rising. In March 1917, Neylon wounded RIC Constable Johns by a shotgun blast. “It put him out of action for a good while and he gave no more trouble after that,” said Neylon.

EASTER 1916

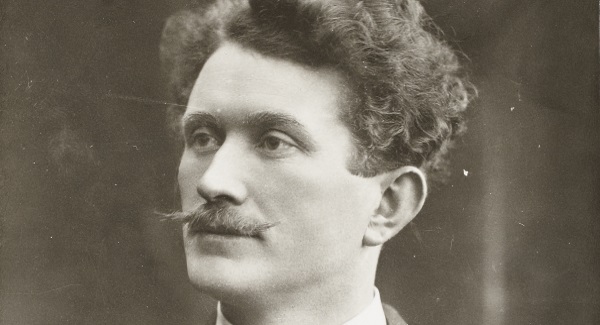

Due to Eoin MacNeill’s countermand to the order for Volunteers to mobilise on Easter Sunday 1916 the majority of the organisation stood down only to bitterly learn later that the Rising had gone ahead in Dublin. Among those arrested was 31-year-old Tomás Ashe.

Ashe was born in Lispole, Kerry, in 1885, became a teacher and taught in Dublin. He was a close friend of the playwright Sean O’Casey and was a cousin of actor Gregory Peck. He became a senior member of the IRB and at Easter 1916 was in action on the outskirts of Dublin where he and fellow

Volunteers engaged the RIC, killing eleven, and losing two men in a five-and-a-half-hour battle. When the Rising collapsed he surrendered on the orders of Pearse and was sentenced to death, a sentence that was commuted to penal servitude for life.

Some Dublin civilians (including the ‘separation allowance women’ – whose husbands were off fighting in WWI) verbally abused the prisoners of Easter 1916 as they were marched off to internment camps and prisons in Britain. Ireland had contributed greatly to the British war effort (and the soldiering tradition, in general), Redmond’s National Volunteers having been seduced by their leader’s propaganda that Britain would see Ireland ‘right’ after the war.

In the various by-elections from 1917 on (won by Sinn Féin) the most bitter and often violent opposition to the republicans came from the Redmondite Party which contained many ex-British Army men. Sinn Féin election workers were physically attacked, six being badly beaten outside the Old Grand Hotel in Ennis by Redmondites and members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. While there was some republican violence Mac Conmara says: “the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that the majority of intimidation and violence, instead of being instigated by Sinn Féin, was largely the preserve of those purporting to stand for a constitutional position.”

After Easter 1916, the Irish Volunteers began reorganising and agitating while being spied on by the Royal Irish Constabulary, the RIC being the eyes and ears of Dublin Castle. The pettiness of the state can be seen in the extent of the repression, arrests for minor offences such as the flying of the Tricolour or the wearing of badges. One Thomas Haverty was prosecuted for shouting, ‘Up the Kaiser’. In Kilkenny the County Inspector reported a priest who was observed singing a rebel song. RIC Constable McCarthy reported Fr Delahunty for singing the ballad ‘Easter Week’ at a concert in Dunamaggan. In Clare nineteen men were summonsed for lighting a fire in celebration of Count Plunkett’s victory in the first by-election in Roscommon in February. In Belfast four men were sentenced to three months for singing in celebration of Plunkett’s victory.

Reading Days of Hunger we learn just how active and to the fore was County Clare in Irish republicanism. I wasn’t aware, for example, that it was the first county to operate a Sinn Féin court in defiance of the Crown.

The Clare Brigade, led by 25-year-old Paddy Brennan, was established in January 1917. At first, the Volunteers throughout Ireland defied British authority through secretly drilling. Brennan felt that while elections were good the Volunteers really needed to ‘put it up to the authorities’: something deeper was required “a more robust and definitive challenge to [the] British.” And so, without consulting GHQ, he began openly drilling men in uniform in the presence of the RIC. This resulted in large scale arrests – but, of course, there were no arrests by the RIC of Ulster Volunteers who openly drilled with impunity.

Brennan also advocated that arrested Volunteers should refuse to recognise the court and that when sentenced they should go on hunger strike demanding political prisoner status. With each arrest new layers of support – from families, relatives, friends and neighbours – were drawn to the cause.

In May 1917 the republican leadership agonised over whether to put forward a prisoner for the South Longford by-election. Again, there are parallels with Bobby Sands’ candidature in Fermanagh and South Tyrone. We were aware that if Bobby lost, even by a few votes, it would be devastating to the prisoners’ campaign and that Thatcher would crow, “Even your own people reject you!” At least Bobby went forward willingly. Back in 1917 there were major divisions over the tactic of putting forward prisoners for election. IRB member Joe McGuinness, who was in Lewes Jail, was opposed to his own nomination, as was his fellow prisoner Eamon de Valera, on the grounds of the risk associated with the potential defeat of a ‘1916 man’.

Ashe, who was also in Lewes, supported participation. The prison leadership sent out word not to put forward McGuinness but Michael Collins brushed aside their objections! The campaign slogan became, ‘Put him in to get him out.’ McGuinness won, but only after a recount which saw thirty-seven votes between him and his nearest rival.

By mid-June the British government announced that it was granting amnesty to “the Irish political prisoners” (sic) of Easter 1916. Among them was Tomás Ashe.

De Valera, on the day he was released, had no qualms about the risk of a ‘1916 man’ being defeated at the ballot box when he agreed to stand in, and then went on to win, East Clare (after the death of Willie Redmond).

Just as in 1981 the British media (and even the Labour Party’s Don Concannon from the floor of the House of Commons) called upon people not to vote for Bobby Sands, the Daily Telegraph in July 1917 said that East Clare, “was the most important election that had ever taken place or ever will take place, in Irish history.” The Telegraph and other establishment bodies urged the people not to support de Valera but to vote for Patrick Lynch of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

De Valera won easily. Retaliation was swift: the RIC opened fire at an election victory celebration in Kerry, killing a young man, Daniel Scallan. Instead of the constable responsible for the shoooting being charged the RIC arrested and charged those who had flown the Tricolour, including nine publicans.

De Valera, in his victory speech, repeated that he was an abstentionist and like the others would not be taking his seat in Westminster – a policy that Dev’s successor, Micheál Martin, has said he would abandon. Talk about moving backwards.

Ashe remained free only a matter of weeks. In August 1917 he was arrested and charged with making a speech in County Longford in contravention of the Defence of the Realm Act. He was sentenced to two years hard labour.

In Mountjoy Jail the atmosphere was tense. After one confrontation – over prisoners breaking the silence rule – the men smashed their windows, bed boards and shelves.

With convictions mounting and the likelihood of a strike now inevitable, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Laurence O’Neill, and John Irwin of the Board of Visitors, appealed to the Chief Secretary Henry Duke and the prison governor Max Green (married to the daughter of John Redmond) to compromise, but to no avail. Green said that the men had been handed to him as criminals and had to be treated accordingly. (Classed as third division offenders they were equated with thieves, burglars and pickpockets.)

On 17th September Tomás Ashe informed the governor that he was refusing to do hard labour. His books and writing material were confiscated. When the prisoners refused to walk in single file around the yard, the right to exercise was withdrawn (again, with uncanny echoes decades later in the H-Blocks and Armagh Gaol). Confined to their cells they smashed their stools, broke windows and broke through the pipes in adjacent cells. The governor then ordered the warders to forcibly remove all bedclothes, mattresses, towels, bibles, shoes and boots from the cells.

The prisoners had a list of eleven demands (including the right to open-air work and free association) which basically amounted to a demand for political status.

At 10am on 20th September, 1917, thirty eight prisoners, including Ashe, refused to take food. Their cells were bare and they slept on a cold stone floor. Sixteen of the thirty-eight prisoners were from Clare, and out of those sixteen, ten, including Ashe, were members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

The British government had earlier decided upon the brutal policy of force-feeding, either through the nose or mouth, and that was to be the practice from the third day of the strike. The body’s natural reaction to being force-fed is to gag and vomit. The rubber tubes used in the procedure were not even sterilised between feeding.

On 25th September, as he was being forcibly fed for the fifth time, food entered Ashe’s lungs, causing asphyxiation. His face turned blue, he became unconscious and suffered the first of two fatal heart attacks. He was removed to the Mater Misericordiae Hospital where he died within a few hours. His body lay in state at the City Hall, dressed in his Volunteer Republican uniform. Thirty-thousand mourners filed past his open coffin to pay their respects.

After his death the hunger strike continued but on the night before his funeral the British government granted political status to the prisoners. The following day the fast was called off, The Times of London declaring it a, ‘Victory For Sinn Féin Prisoners.’

Thousands attended his funeral procession, and comparisons were made with the numbers who had been at Parnell’s interment twenty-seven years earlier. At his graveside in Glasnevin Cemetery Michael Collins gave what must be the shortest eulogy in history: “The volley that we have just heard is the only speech that is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian.”

As Mac Conmara writes: “From the hunger strike onwards, the political balance swung against British policy… In their attempt to de-legitimise the rebels, the British authorities had instead afforded a heightened credence, not only to the hunger strikers, but to the movement far beyond the interior of Mountjoy Prison.’ Or, as it was put by the London Daily News: Ashe’s death had made ‘100,000 Sinn Féiners out of 100,000 constitutional nationalists.’

When the Clare prisoners were released in November 1917, before going home, they marched to Glasnevin and to the grave of Ashe where they stood in silence in honour of their comrade.

Then they went home to oil their guns.