The difficulties of dealing with the past has been dominated by and largely associated with the recent conflict in the North. But the decision by the Irish government to commemorate members of the RIC and the Dublin Metropolitan Police prior to the establishment of the Free State in 1921, has caused political controversy and a social media storm. Fianna Fáil Mayor of Clare, and general election candidate, Cathal Crowe, announced yesterday that he has turned down an invitation to attend a memorial service in Dublin Castle issued by the Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan. Crowe said the decision to commemorate the RIC is “revisionism gone a step too far”.

In April 1919, Dáil Éireann declared a boycott of the police. The mass burning of RIC barracks began in January 1920. Britain then sent in the mercenary Black and Tans and Auxiliaries to bolster the role of the RIC.

IRA KILLS 500

In the subsequent struggle for independence the IRA killed over five hundred members of the RIC. When Seán Mac Eoin (later, Fine Gael’s 1945 presidential candidate) was the leader of an IRA Flying Column in Longford in 1920 he had been responsible for killing up to two dozen of his fellow Roman Catholic Irishmen in the RIC. A small sample includes: 23-year-old John Kelleher from Cork who had only been in the RIC four months; 45-year-old Constable Peter Cooney, a married man, shot in the back whilst returning from leave; and 30-year-old District Inspector Thomas McGrath, a single man from County Limerick, shot through the head by Mac Eoin when he knocked on Mac Eoin’s door.

Men like Mac Eoin shot and bombed British soldiers and RIC men, killed them where they could – on holiday, on leave, coming out of Mass, feeding the cows, in bed with their wives, at their dinner tables, on patrol and in the barracks. Mac Eoin saw the RIC as British agents.

Those Who Fought The RIC

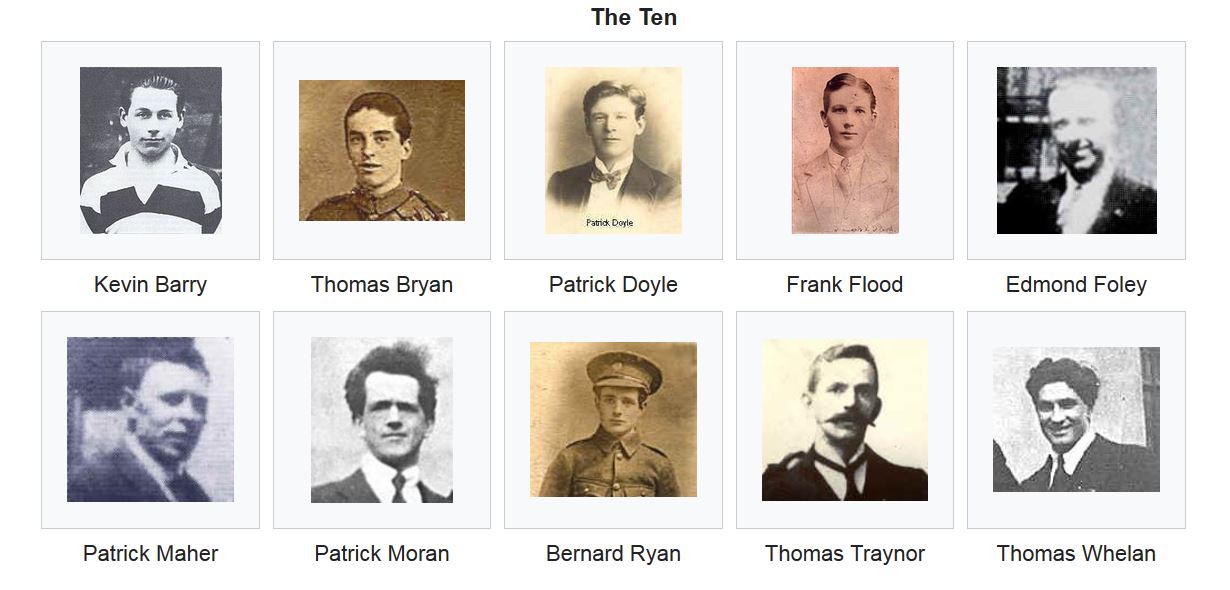

In 2001 the bodies of Kevin Barry and nine other IRA Volunteers, who had fought the British army and RIC men, and who had been hanged by the British in 1920 and 1921 and then buried in the grounds of Mountjoy Prison, were given what amounted to state funerals. Nine of the ten were taken to Glasnevin Cemetery where they were reinterred; the tenth, that of Patrick Maher, was buried six days later in Limerick, at the request of his family.

In 2001, I worked for the Irish Examiner and wrote this feature, which at the time was largely aimed at the media, but also deals with the hypocrisy and double-standards of those political parties in the South which twist history because of its inconvenient truths, particularly in relation to the cause of the IRA campaign in the North and the IRA’s methods, which were no different from those used in 1919 and 1920 by the IRA – from which both Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil claim lineage.

FOR THE CAUSE OF LIBERTY

Why could they not be exhumed and reburied in private, asked Chris Ryder of the Sunday Times about next week’s state funerals in Dublin for the re-interment of ten IRA Volunteers who were executed by the British in 1920 and 1921.

‘Like the Americans of today,’ wrote Paddy Murray in the Sunday Tribune, equating ‘the murderous deeds’ of the Volunteers of the war of independence with the suicide bombers who flew into the World Trade Centre, ‘they [the British] demanded retribution. Kevin Barry and nine others provided that retribution with their deaths.’

The funerals, wrote Fintan O’Toole in the Irish Times, will offer ‘a great boost to those who want us to feel that the only difference between a terrorist and a patriot is the passage of time.’ That is, Kevin Barry and, by implication, the rest of the IRA were terrorists. If that is the case what does that make their hangmen, the British? Well, I suppose they were just here reading us Jane Austen, teaching us cricket and helping our little nation to develop its natural resources.

Kevin Myers, also in the Irish Times, complains that next week’s event is all about reaffirming ‘a single narrative of suffering and sacrifice’. I don’t know why. He seems to know the name of every British soldier killed by the IRA since 1916, or who died at the Somme and Passchendale. He has been writing their stories for years. He doesn’t write about Germans. Is he not guilty of reaffirming ‘a single narrative of suffering’? Calling for reprisals, after the recent bombing of New York and Washington, he wrote that he was all-the-way-with-the-USA, even though ‘mistakes will be made’. So, it would appear that it is not the act of killing/terrorism, after all, that is objectionable, but the cause on behalf of which it is carried out.

These commentators, and opposition Labour leader Ruairi Quinn, have also alleged that the funerals are a cynical exploitation by Fianna Fáil, aimed at stealing what’s assumed to be Sinn Féin’s clothes and minimise that party’s anticipated electoral advances. The oration, televised live, will be delivered by Taoiseach Bertie Ahern in Glasnevin Cemetery where Pearse spoke over the remains of O’Donovan Ross. (However, don’t be expecting ‘Ireland unfree shall never be at peace’, nor, hopefully, anything as gauche as ‘Kevin Barry would have supported Fianna Fáil, NATO etc.’)

The oration will be delivered on the eve of the Fianna Fáil ard fheis and it is suggested that this is no coincidence. After all, Fianna Fáil had ample opportunity to exhume the bodies during its many lengthy periods of government in the 1930s (before it brought in the English hangman, Pierrepoint, in the 1940s to execute IRA men), in the 1950s and, for example, in 1966 during the golden jubilee of the 1916 Rising when pageantry was at its optimum. It chose to leave them lying in prison yards. At any stage, even during the recent conflict, it could have released the remains to the next-of-kin, but chose not to.

After the IRA ceasefire in 1994 spokespersons for the National Graves Association and Sinn Féin raised the issue of exhumation and re-interment with the Irish government and in letters to the press (just as they did in regard to the remains of Tom Williams, whose remains the British released from Crumlin Road Jail for reburial two years ago). As far as I know, no request was made for a state funeral. However, even if the timing of the re-interments is suspect, for nationally-minded people, which includes most of Fianna Fáil and its supporters, these funerals represent due honour to patriots who sacrificed their lives in the struggle for independence.

What many of the opponents of the state funerals resent is the fact that the event is actually tapping into a buoyant public mood that they have strived for years to repress. These people would have Ireland feel guilty about its past, without begging the same moral question of Britain about its disastrous role in Irish affairs. Kevin and Fintan, and whoever, can choose not to like their grandparents, figuratively speaking, but they shouldn’t get away with imposing that piece of Freud on the rest of us.

For phrases such as ‘sending a dangerous signal to impressionable young people’ and ‘will be widely and dangerously misunderstood’, read ‘the people are stupid and we have to save them from themselves.’ It is nonsense to suggest that for the country to pay its respects in this grand manner now makes its citizens retrospective conspirators to shootings and bombings, or that it legitimises the recent IRA campaign, or acts as a recruiting sergeant for the IRA. Ask any ex-republican prisoner or IRA Volunteer to name who influenced their decision the most to join the IRA. It will not be Kevin Barry. It will be, ‘a British soldier.’

Anyone who has read the book Curious Journey, an oral history of the Tan War period, in which IRA veterans express their regret (and sometimes weep) for the suffering and death their actions caused, whilst not balking at the stance they took, will realise that these men and women are the first to acknowledge the ambiguities and complexities all conflicts throw up. These ten dead men were their comrades and for forfeiting their lives on our behalf they deserve the few hours of public honour they shall receive next Sunday.

Click here for interviews from 1970 of those who fought with Kevin Barry in 1920