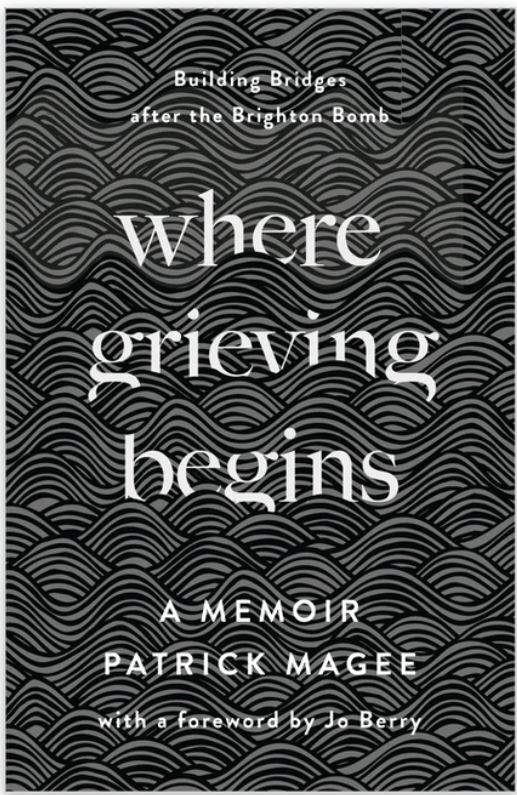

Andrée Murphy reviews the recently published memoir, Where Grieving Begins, by former IRA Volunteer Pat Magee, with a foreword by Jo Berry whose father was killed in the Brighton Bombing. It is published by Pluto Press. Pat was sentenced to multiple terms of life imprisonment, convicted of planting the bomb at the Grand Hotel in Brighton in 1984 from which Margaret Thatcher had a narrow escape. Since his release from prison after the Good Friday Agreement, he has worked towards building a common understanding of the past. He completed his PhD whilst in prison, and is the author of Gangsters or Guerrillas? Representations of Irish Republicans in Troubles Fiction (Beyond the Pale Publications, 2001);

HONEST AND PAINFUL

Pat Magee’s extraordinary book is a tale of two halves. The first is something that might read quite familiarly to those versed in the conflict in the North of Ireland. It is the journey of a young man and an ordinary family from a life of discrimination to one of military conflict. There are shocking examples of brutality that will resonate for the lack of appreciation of their impact and impunity. The almost routine nature of state violence is noticed and explored in a way which, despite being familiar, feels fresh and important.

The second half of the book however is where the journey becomes far less familiar, a wholly unique story of a personal coming to terms with individual and collective acts of resistance and resulting harms.

Pat Magee readily acknowledges from the outset how he is described as the ‘Brighton Bomber’ and what that implies for him as he tries to engage with recording his experiences. He in no way resiles from the soldier he became or the consequences of that choice from experiencing and inflicting harm which led, for him, to multiple terms of imprisonment. The theme of the book is how complex and complicated it can be to regret the impact of the taking of life, while at the same time explaining the context of that action. But most importantly it is a record of how, despite its difficulty, that process is not only possible but something to be shared. The book’s particular importance lies in that message.

with recording his experiences. He in no way resiles from the soldier he became or the consequences of that choice from experiencing and inflicting harm which led, for him, to multiple terms of imprisonment. The theme of the book is how complex and complicated it can be to regret the impact of the taking of life, while at the same time explaining the context of that action. But most importantly it is a record of how, despite its difficulty, that process is not only possible but something to be shared. The book’s particular importance lies in that message.

This is a timely conversation. Set in the context of a wider societal conversation on dealing with the past where it seems the British state is happier to sidestep the consequences of its actions, for fear of embarrassment or loss of face, Pat Magee’s book demonstrates that engagement in those complexities is very possible and indeed necessary as part of individual and societal post-conflict healing. It blows narratives of the singular primacy of ‘innocent victims’ and need for repentance out of the water as it engages with layers of victimhood and themes of acknowledgement and responsibility. This is not a journey for the faint-hearted; neither is engaging with the challenges posed by the book. But nonetheless the reader is left feeling that such processes are vital all the same.

What is particularly important is the role of others who make space for safe conversations. Magee’s journey is not an individual effort.

Pat Magee speaks emotionally and caringly about the special relationship he has developed with Jo Berry, who writes the incredibly honest forward. Jo Berry’s father was killed by Magee’s bomb at the Conservative Party conference in Brighton in 1984. Her readiness to engage in such direct and painful conversation is not routine. Neither is the approach of Magee himself. They are both very special people, and clearly have a very special relationship. But the book gives an insight into what allows that to happen. It is not just the two special individuals. There are lessons on process. On facilitation. On support from outside actors. It is also instructive on what can harm processes of reconciliation—not least external political developments.

The book also engages with the role of the media in these processes. Pat Magee and Jo Berry negotiated a very safe and controlled path for their media engagements and for some of the time it was clearly useful. Yet that was not always a happy experience and there is much learning to be gained from how the media can be useful and necessary in exploring complex issues of reconciliation but how the leanings to simplistic narratives are destructive.

A question arises however while reading the book. Pat Magee and Jo Berry’s remarkable and unique journey has not gained the currency that it should have. Reading this book clearly tells us that both of them have much to teach us and their experience should be routinely informing and framing wider conversations, yet somehow they are not. One wonders if Pat Magee had engaged in a process of repentance rather than the complex and honest dialogue that he and Jo Berry chose to have, would he and she be hailed and promoted differently? Had Patrick Magee expressed his view of history and participation in the IRA in a more status quo fashion would we be more familiar with his chosen model of reconciliation and dialogue? Indeed, in part of the book he describes his and Jo’s efforts to launch strategic initiatives which could create understanding, and how there was a reticence to embrace him as a key actor in that.

However, in our unreconciled society we have seen how easy answers to themes of reconciliation have often failed and crass or simplistic ‘community relations’ efforts barely scratch the surface. Despite this it seems that the honest and all the more painful process of understanding both Jo Berry and Pat Magee engaged in, one where neither felt compelled to disown their politics or their backgrounds, is less appreciated. This book should make many think again about the contribution their process could yet offer.

Pat Magee’s honesty about how his own journey of reconciliation was received in his own community is something I have not read before and is instructive of wider society’s failures on so many different levels to deal with the past.

This book should reignite our commitments to safe and positive engagements with each other. It should encourage bravery and leaps of faith. Pat Magee didn’t just get to know Jo Berry—he got to know himself. Of course, not every victim wants to meet the person responsible. And of course it would not always be healthy or safe. It is the process and the intention of process of reconciliation that is important and sings off the pages. Magee and Berry wanted to contribute outwardly as they engaged with their internal questions and conflicts. Magee’s engagements with Jo Berry and his efforts to contribute to reconciliation is a parallel journey to the peace process itself and to the unaddressed question of dealing with the past. Lessons of generosity, acceptance and respect could and should be learned from this book. And one that says better is possible.