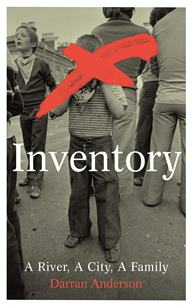

Inventory – A Family Portrait of Derry’s Troubled Past By Darran Anderson, Vintage, £8.99, 320pp

My review in The Irish Examiner, 3 October, 2020

THERE have been many excellent memoirs written from the northern nationalist perspective. Among the best are Bernadette Devlin McAliskey’s The Price Of My Soul, Dennis Donoghue’s Warrenpoint, Seamus Deane’s Reading in the Dark, and Tony Doherty’s tender and moving This Man’s Wee Boy.

What historians – with their attention to the ‘big picture’, their fixation with dates, statistics, conferences, legislation and (usually) ‘great’ men at war – rarely capture is the psyche of ordinary people, the raw communal experience and reaction to critical events (which also drives and determines history), the multi-layered humanity of a community, which the memoir can crucially make up for.

Colin Broderick’s astonishment and sense of abandonment (That’s That, 2013) discovering on a London building-site in the late1980s that many of his fellow labourers, hailing from Cork and Kerry, couldn’t give a damn about the punishment his people in Tyrone were going through at the hands of the British army, was an emotional reaction to an attitude coldly fostered by the Irish establishment. For almost a century, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil and earlier incarnations, and for two decades RTE’s Section 31’s censorship, politically and deliberately distanced the state and the people from the northern nationalist community, a community sacrificed to partition so that Twenty-Six Counties could be free.

One of the greatest and ongoing insults is to have politicians and commentators consciously refer to the Republic of Ireland (which stops at the border) as ‘Ireland’, perpetuating the very partition (and mindset) they sometimes claim to decry.

Inventory by Darran Anderson, as well as being a coming-of-age memoir set in Derry, opening in 1984, is a study of innocence and guilt, culture and history, war and peace, hearth and home versus his personal odyssey (into the underworld and the horrors and false solace of those two crooks, alcohol and drugs), and ultimately finding liberation and redemption through self-exile and the expressive power of the written word.

He is a fine, accomplished writer.

A Russian proverb prefacing the book, paraphrased, reads – Dwell on the past and you’ll lose an eye. Forget the past and you’ll lose both eyes.

A Russian proverb prefacing the book, paraphrased, reads – Dwell on the past and you’ll lose an eye. Forget the past and you’ll lose both eyes.

His mother was pregnant with him when she and his father were living in Cork but returned to Derry to get married, her father disapproving of the union and ostracising her. Life was poor, the streets were tough, and young Darran was an inquisitive child, a habitual reader who later described this compulsion as ‘a dangerous curiosity’, earning him the sobriquet from his mother, ‘Professor Anderson’.

Beyond the door were patrolling British soldiers and the family would secretly tune into their radio frequencies to plot the movement of raiding parties. Anderson was young enough to escape the pull of the IRA (on the eve of cease firing) but observes: “People didn’t need to choose to become explicitly involved. They already were, by geography, class and genealogy.”

As an urchin, a juvenile adventurer, an underage drinker, he was continually inhabiting ‘a place between fiction and reality’.

These were the days of video shops, BMX bikes, early home computers, hiding in ‘the Glen’ and observing an army patrol through his little periscope, aware that he could be shot dead if he gave himself away. Death was prevalent. His young cousin Rory is knocked down and killed by a van. An older cousin hangs himself in a barn.

Given the generational poverty and the lack of opportunity it should come as no surprise to discover that Darran’s paternal grandfather (like thousands of others across Ireland, my own included) joined British forces during WWII. However, he was a serial army deserter, and drinker, and drowned in the River Foyle at the age of thirty nine, where into the dark, cold waters twenty years later his wife, Granny Needles, followed him. The teenage son of another cousin also drowned himself – the search for his remains becoming an introspective search for meaning from the anarchy of life.

The most powerful chapter is called Inventory and consists of a random list of the dead of the conflict and their dying.

Against a background of such morbidity it is miraculous that a cosmopolitan writer as bright and optimistic as Anderson emerged. His eureka moment comes after a bloody street fight, drunk in Belfast’s student land, having dropped out of university, and sitting perilously on a roof looking towards the Central Library from which he is barred.

He turns to his friend Liam and says, “I’ll write about this one day.”

And he does! Awesomely.