How other writers work and compose interests me; which is why I often read many books which provide an insight into the writing life. There were several positive reviews of Graham Swift’s ‘Making An Elephant’ some months back and so I ordered it from my local library. The interesting aspects outweigh its flaws – for example, it is a bit too self-indulgent (the forty pages of poems; the gushing references to tales of bonding with fellow writers despite Swift’s declared penchant for solitariness), and it appears to be an exercise in preserving for posterity earlier material of which the author is clearly proud.

Nevertheless, I enjoyed the book and read it in a few days, about 70 or 80 pages at a time, even though I suffer from eye strain. My sight has deteriorated over the years and I have recurring, running tears from my left eye (which gives the impression particularly in the cinema that I am crying!).

I love Swift’s honesty. He says that “writers are basically just people who are trying to organize their confusion”. He records that he turned up at various readings or launches when there was no audience. He appears to be in thrall to no one.

About his writing life he says: “My fountain pens are very precious to me and I would never take them out of the house. I’ve written three novels with my current pen and all the others were written with another fountain pen, which died, but I still have it. I’m very much a hand-writer.”

Interestingly, given what creative writing students are normally told he says:

“My instinct goes against the advice that writers are often given: ‘show, don’t tell’. In many cases you should show rather than tell, if that effectively means show rather than explain. But the word ‘tell’ is a great word. It means more than just the simple ‘I am telling you this thing.’ We use it in so many ways. ‘I can tell,’ means something quite different from the business of relating something; it suggests knowing and understanding, a seeing into the situation. There are times when what you have to do is not show, which would be almost the easy, even the evasive thing, but find a way of telling.”

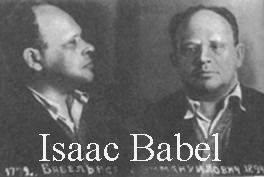

As a result of reading this book I shall now go and read Montaigne’s essays, ferret out the work of Russian writer Isaac Babel and the Czech author Jiri Wolf.

Babel was a short-story writer noted for his war stories and Odessa tales. As a soldier in the war with Poland came the stories ‘Red Cavalry’ [1926]. The ‘Odessa Tales’ were published in 1931. The cycle of realistic and humorous sketches [and here I am paraphrasing from Merriam Webster] of the Moldavanka – the ghetto suburb of Odessa – vividly portrays the life-style and jargon of a group of Jewish bandits and gangsters, led by their ‘king’, the legendary Benya Krik. After the mid-1930s Babel lived in silence and obscurity. In May 1939 he was arrested and died in a prison camp in Siberia on 17th March 1941. And just for writing words.

A phrase is born into the world both good and bad at the same time. The secret lies in a slight, an almost invisible twist. The lever should rest in your hand, getting warm, and you can only turn it once, not twice.

Beyond the window, night stands like a black column . . . A shadowy radiance lies on the earth, and hanging from the bushes are necklaces of gleaming fruit.

Both of us looked on the world as a meadow in May – a meadow traversed by women and houses.

No steel can pierce the human heart so chillingly as a period at the right moment. [No iron can stab the heart with such force as a full stop put just at the right place.]

Now a man talks frankly only with his wife, at night, with the blanket over his head.

On Sabbath eves I am oppressed . . . O the rotted Talmuds of my childhood! O the dense melancholy of memories!

The bee of sorrow had stung his heart.

They didn’t let me finish. [To his wife, on the day of his arrest.]

You’re trying to live without enemies. That’s all you think about, not having enemies.