You certainly learn something all the time and I was disappointed and annoyed to discover from Jenny Williams’ book on Hans Fallada (‘More Lives Than One’) that when he was imprisoned he was “rewarded not only by being promoted to the rank of a trustee but also by being released over a month early. One of the reasons for his success in prison was his willingness to ‘squeal’ on his fellow inmates. He is commendably honest in assessing his actions and admits to being ashamed: ‘But that’s life. I have to survive. Let stronger men be heroes and martyrs, I have only enough talent to be a small-scale coward’ (4 July 1924)”.

In that sense he reminds me of some things I read by Jean Genet and Francis Stuart.

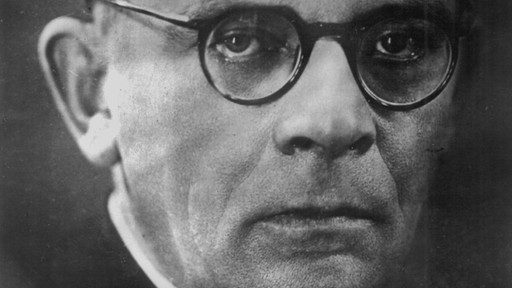

In the introduction Williams described Fallada, real name Rudolf Ditzen, as “a remarkable man – among other things an alcoholic, drug addict, womanizer, jailbird and thief, in his time wooed by both the Nazi and the Soviet cultural authorities…

“After the war, in the Soviet zone of occupation, Ditzen enjoyed the patronage of Johannes R. Becher, the senior literary figure among those German Communists who returned from exile in the USSR, and there in 1946 he wrote the first anti-fascist novel of the post-war period, Alone in Berlin.

“… as the narrator of The Magic Mountain said of Hans Castorp, Ditzen, too, lived ‘not only his personal life, as an individual, but also, consciously or unconsciously, the life of his epoch and his contemporaries’.”

On WWI: “Many writers, artists and intellectuals supported the war effort. Thomas Mann declared in September 1914: ‘War! It was purification, it was liberation, that we felt and enormous hope.’”

The Fallada name: His literary persona came from “the world of Grimms’ Fairy Tales: Hans, from the protagonist of ‘Lucky Hans’, an easily duped but happy-go-lucky young man, and Fallada from the horse called Falada in ‘The Goose Girl’ who, even at the cost of his own life, and after death, always told the truth and ensured that justice was done.”

Kafka on writing: “’The strange, mysterious, perhaps dangerous, perhaps saving comfort that there is in writing: it is a leap out of murderers’ row; it is a seeing of what is really taking place.’”

Inflation [and the rise of Hitler]: “Wilhelm and Elisabeth Ditzen [his parents] shared the fate of many middle-class Germans in 1923, watching helplessly as their pensions and savings were eroded by inflation. Wilhelm Ditzen described a journey in the summer of 1923 to Blankenburg in the Harz mountains, when the ‘fourth-class railway-ticket cost 58,000 marks on the way there and 580,000 marks on the way back. The next day the price would have been 2,320,000 marks.’…

“By the end of July, three hundred paper mills were working full time in Germany to provide enough paper for the one hundred and fifty printing companies that were operating twenty-four-hour shifts producing banknotes.”

Writing: He was an incredibly fast writer and to do so he required large quantities of coffee and tobacco, “both of which the doctor who had examined his heart in April had advised him to avoid.”

Banned Books, 1933: “The list of banned books included works by Becher, Brecht, the Mann brothers, Tucholsky, Feuchtwanger, the two Zweigs, Kästner, Remarque, Ossietzky, Alfred Kerr, and many others. The number of banned books rose to some four thousand in the next two years.” Later, Jenny Williams writes: “Emigration was not an easy option: his fellow Rowohlt author Kurt Tucholsky had committed suicide in Sweden in 1935; Heinz Kiwitz went missing, presumed dead, in the Spanish Civil War; Franz Hessel died in France in 1941; Ernst Toller, Walter Benjamin, Stefan Zweig and Walter Hasenclever were all to take their lives in exile.”

Ditzen complains to a friend about the interference in his writing: ‘I have been practically forbidden to depict shady characters. Only the Good, Pure and Decent – but that produces no problems that are worth depicting.’

Goebbels: Is under pressure to meet Goebbels but procrastinates. Goebells says, “If Fallada still does not know his attitude to the Party, the Party has no doubts about its attitude to him!’

Ditzen capitulates in the writing of ‘Iron Gustav’ and tries to explain it: ‘I do not like grand gestures, being slaughtered before the tyrant’s throne, senselessly, to the benefits of no one and to the detriment of my children, that is not my way.’”

“He glosses over his compliance with Goebbels’s instructions about the conclusion of ‘Iron Gustav’ and claims that those, like himself, who stayed in Germany and did not get involved in ‘ridiculous enterprises such as conspiracies or coups d’etat’ were ‘the salt of the earth’.”

Definition of Courage: “It is likely that, in 1937, Ditzen shared Wolfgang Pagel’s definition of courage: ‘I used to think that courage meant standing up straight when a shell exploded and taking your share of the shrapnel. Now I know that’s mere stupidity and bravado; courage means keeping going when something becomes completely unbearable.’

Writer’s Function: “Peter Suhrkamp was to formulate a similar definition of the writer’s function in Nazi Germany: ‘To give people courage, the courage to face life, is probably the best gift a writer can bestow. The courage to face life is different from the courage to face war. In the same way that to withstand an attack is more difficult than to launch one.’”

German Nation Despised: “He confided in a letter to Paul Bruse, mayor of Neustrelitz: ‘I never fail to be deeply disturbed by how the Germans show themselves to be so wretched in defeat; with very few exceptions they prove that the world is quite right to despise the German nation.’”

(If you have not yet read ‘Alone In Berlin’ then certainly do not read the following which is about the origin of this true story.)

In the Soviet Zone of Germany he is taken under the wing of Johannes R. Becher, a communist and poet. It was he who passed on to him “a Gestapo file relating to the case of a working-class couple, Otto and Elise Hampel, who had been executed in 1943 for distributing anti-fascist material. Becher, who clearly knew Ditzen’s interests as a novelist, shrewdly chose a tale of two ordinary people who had no links to the Resistance and who carried on their hopeless struggle in isolation and with heroic single-mindedness. However, Ditzen did not receive the complete Gestapo file: he appears not to have seen the final volume, which contains the documents after sentencing in which the Hampels, who had not expected a death sentence, break down and accuse each other of instigating the campaign against Hitler in a fruitless attempt to escape execution. Ditzen was thus able to portray the Hampels as heroic to the end. The reason why the Gestapo file was incomplete is unclear.”