The New York Review Books Classics, which started in 1999, is a treasure trove of fiction and non-fiction and includes titles from the traditional canon but also books from across the world that fell into obscurity or that had not been translated into English. I have just finished reading two of their publications.

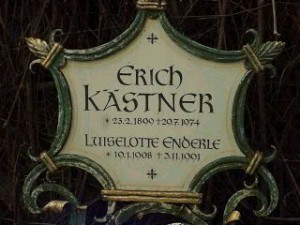

I first read Erich Kästner’s novel about twenty years ago when it was titled Fabian but under this imprint it is now titled, Going To The Dogs, the title he preferred but which was rejected by his original publisher in 1931. (I actually prefer Fabian!) The tragic novel is about thirty-two-year old Jakob Fabian, an advertising copywriter, in Berlin in 1929/30 in the dying days of the Weimar Republic, and I quote passages from it in my book, Then The Walls Came Down. When I was in Munich last November I made a point of visiting Kästner’s grave.

So I read his classic, back-to-back with the brilliantly written/translated non-fiction, Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck (pic, below right), which charts the period 1936-44 under Hitler. Reck was a novelist but also a writer of children’s adventure stories.

So I read his classic, back-to-back with the brilliantly written/translated non-fiction, Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck (pic, below right), which charts the period 1936-44 under Hitler. Reck was a novelist but also a writer of children’s adventure stories.

There is an episode when Fabian addresses the corpse of Labude, his friend, who has committed suicide. The novel was produced in circumstances when the Nazis were on the rise but when some, including Kästner still thought that the left would fight back. Fabian, who is alienated from all sides, a man also in despair, says: “Listen! Soon an embittered struggle will begin, first for mere bread and butter, then for the plush sofas; the one side will strive to retain them, the other side to secure them. Titanic blows will be struck and finally they will hack the sofas to pieces, so that no one shall possess them. There will be mountebanks on all sides among the leaders, men who invent proud phrases and grow drunk with the sound of their own voices. There may be two or three real men among them. If they tell the truth twice running they will be hanged.”

Reck’s book deals with the period when Hitler has assumed full power and is a contemporaneous account of life under the Nazis as observed and monitored by Reck or assembled from what he hears. The accuracy of some of the anecdotal material and Reck’s reminiscences were challenged in the 1970s but in my opinion even if flawed or exaggerated they do not undermine the spirit of Reck’s writings or his contention that many Germans hated and reviled the Nazis. Reck was an arch-conservative with pseudo-aristocratic pretensions, was arrogant and had no love for the working class or labour, but nor for the fanatical Prussian aristocrats who backed Hitler.

Reck’s book deals with the period when Hitler has assumed full power and is a contemporaneous account of life under the Nazis as observed and monitored by Reck or assembled from what he hears. The accuracy of some of the anecdotal material and Reck’s reminiscences were challenged in the 1970s but in my opinion even if flawed or exaggerated they do not undermine the spirit of Reck’s writings or his contention that many Germans hated and reviled the Nazis. Reck was an arch-conservative with pseudo-aristocratic pretensions, was arrogant and had no love for the working class or labour, but nor for the fanatical Prussian aristocrats who backed Hitler.

He wrote not daily but weekly or monthly and hid his notebooks on the land around his estate.

In 1936 he writes: “My life in this pit will soon enter its fifth year. For more than forty-two months, I have thought hate, have lain down with hate in my heart, have dreamed hate and awakened with hate. I suffocate in the knowledge that I am the prisoner of a horde of vicious apes, and I rack my brains over the perpetual riddle of how this same people which so jealously watched over its rights a few years ago can have sunk into this stupor, in which is not only allows itself to be dominated by the street-corner idlers of yesterday, but actually, height of shame, is incapable any longer of perceiving its shame for the shame that it is.”

He foretells catastrophe and a second world war and is convinced that the German people are due a divine punishment, the enormity of which they cannot even realise. He says about the demise of Hitler, “the end will come down upon his head from every possible direction, and from places, even, that were never thought of.” But he also blames the rest of Europe for allowing Hitler to come to power and grow in power by not reigning him in and when he first breached international peace, his annexation of Austria and invasion of Czechoslovakia . “And as he is made more powerful, we, who are his last opponents inside Germany, are made weaker and more impotent.”

“They are standing by and watching, preoccupied with figuring out a way to avoid irritating Herr Hitler – and so making any resistance even more impossible. In time to come, you will be able to do certain things: you will be able to punish those who with their wretched political deals made possible that infamous day in January 1933; and you will be able to punish the military and industrial men-behind-the-scenes. But one thing you will not be able to do: you will not be able to make the whole nation, in extensor, responsible for a regime which you – yes, you – have strengthened. You have broken our internal resistance through political lethargy, and you are nevertheless demanding of an unarmed people that they do what you, with your mighty armies and the most powerful navy in the world, do not dare.”

As war breaks out and as time goes on and even more unconscionable reports about the massacres of innocents leaks out, Reck looks forward to the defeat of his own country: “These are the lengths to which we have been driven: that we, who are not the worst of the Germans, must now put our hopes in a war to free us of a plague of locusts.”

He rejoices at the Anglo-American landing in North Africa in 1943: “Despite the ban on listening to the Allied radio, the news spread within an hour. And I was even more amazed, that gray November day, to see the reaction the news produced. Everyone seemed glad about this decisive change in the course of the war, which meant the defeat of his own country… the whole town – the whole region, really – was as exhilarated as though everybody had drunk a bottle of champagne. Suddenly, people walked straighter, and their faces shone, and it was as though a long, hard winter had been endured and now the first warm wind was blowing over the ice. Everyone sensed that a ghostly hand had nailed the death warrant of the Nazis to the wall, and this had a salutary effect on the bad as it did on the good.”

Tragically, Reck’s outspokenness was to lead to his eventual arrest. He was charged with “insulting the German currency” and he died of typhus in Dachau concentration camp in February 1945, three months before the end of the war.