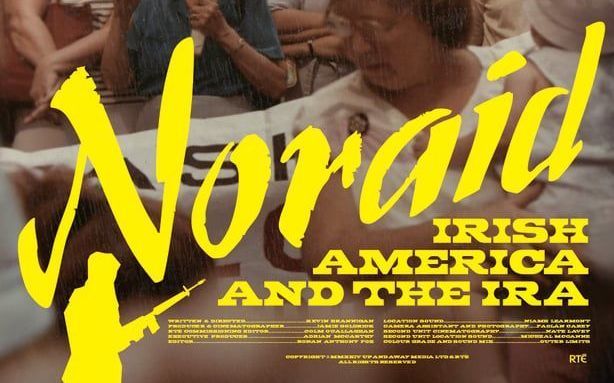

Ciaran Quinn, Sinn Féin Representative to North America, here reviews the RTÉ documentary, NORAID: Irish America and the IRA. The first part was broadcast last Wednesday and the final episode goes out tonight at 21.25. Both can also be viewed now on the RTÉ Player.

The programme is promoted as a ‘look at the Irish-Americans who wanted to do more for the Republican Movement than just fundraise for the families of prisoners’, though Quinn argues that the relationship between the Irish diaspora and Irish republicanism is often misrepresented, or conflated for simplistic reasons.

-ooOoo-

IT is a Belfast truism that ‘we are where we are, because of all that came before us’. I was reminded of that after watching the recent two-part documentary on Irish Northern Aid aired on RTÉ. The documentary, NORAID: Irish America and the IRA, was produced by the Dublin-based PushPull Media and directed by Kevin Brannigan and draws on archive footage and interviews with key players at the time, including Danny Morrison.

There is a pulsating urgency to the production, soundtrack, and editing of the documentary, reflecting the frantic energy of a time of conflict. The producers capture the culture and feel of the 1970s and 1980s to match the footage.

The story of Irish Northern Aid (aka the INA or Noraid) mirrors developments in Ireland. It is also an essential element in understanding the role that Irish America plays in shaping political progress.

Noraid was established shortly after the outbreak of conflict and a split between different wings of the Republican Movement in 1970. It drew together supporters in the US to raise funds for the dependents of internees, innocent nationalists imprisoned by the British state, and IRA prisoners.

Throughout the thirty years of conflict, it has been estimated that 24,000 Irish republicans were imprisoned, with the vast majority of those being associated with the IRA. Many had families, and with imprisonment came the loss of income and the expense of visiting jails and supporting loved ones. The contribution of Noraid, as well as other prisoner groups, was essential for these families.

Support for Noraid increased as the conflict deepened in the early 1970s. Irish America was witnessing in their homes attacks on civil rights marchers, daily violence, and events such as Bloody Sunday. They wanted to do something, and financial support for Noraid grew.

With the 1981 hunger strike, support again began to assert itself in fundraising and also political actions, with protests against British interests, lobbying US politicians to speak out in support of the prisoners, and highlighting the injustice of partition.

It was no coincidence that as Noraid became a more influential political force, the more the British and Irish governments sought to marginalise the group. Britain banned the then Noraid spokesperson Martin Galvin from entering the North of Ireland. They had also banned Sinn Féin leaders from entering Britain. A bar that was extended to the US by successive administrations (‘censorship by visa denial’). On top of that, Sinn Féin’s elected representative were subject to Thatcher’s Broadcasing Ban.

Critics wrongly claimed that Noraid was a front for IRA gun running, a claim dispelled in the documentary by the leaders of Noraid and by IRA members.

Following the hunger strikes, there was a recognition both in Ireland and the US of the potential to build political support for Irish republicanism, Sinn Féin, and Noraid. Noraid became active alongside other groups in campaigns such as the MacBride Principles.

At the 1992 New York Irish America Presidential Forum Martin Galvin of Noraid was included in a panel to question the candidates. The Irish government boycotted the event in protest. The first question of the night was from the Boston Mayor Ray Flynn seeking the appointment of a special peace envoy to the North of Ireland. Bill Clinton agreed to the proposal. Galvin later asked if the candidates would support a visa for Sinn Féin President and MP for West Belfast, Gerry Adams. Clinton said yes.

We had now entered a new phase in the political process. A wider coalition of Irish America would be required to ensure the promises made on the campaign trail would become policy. This included the well-documented role of Niall O’Dowd, Bruce Morrison, Bill Flynn and others that would become known in Belfast as the Connolly House Group

As president, Bill Clinton kept those commitments, and the rest, as they say, is history.

In the subsequent years, Sinn Féin leaders would engaged directly with Irish America, US political leaders, and successive administrations. They could also fundraise for the party, something that was outside the role of Noraid.

Consequently, Friends of Sinn Féin USA was established to meet these new opportunities. It opened an office in Washington (as outlined in Rita O’Hare’s memoir, Rita) and offered a direct line of communication between the party, supporters, and political leaders in the US.

Eight years after that Presidential forum, the remaining IRA prisoners were released. In many ways, with the original mandate of Noraid having been met, Noraid added to its objectives support for the Good Friday Agreement.

As in Ireland, the transition from resistance struggle to peace process was not easy or straightforward. With prisoners reunited with their families, some Noraid activists moved on with their lives as support for the prisoners had been their raison d’être.

Many more stayed engaged, supported Sinn Féin, and shaped political progress in Ireland.

Others, such as Martin Galvin, who features prominently in the documentary, left Noraid and would go on to denounce the Sinn Féin leadership and the Good Friday Agreement at events organised by the Thirty-Two County Sovereignty Movement, aligned to the dissident group responsible for the Omagh Bombing.

Today, however, he is a member of, and represents the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an Irish and Catholic organisation that supports the Good Friday Agreement and the peace process. Martin remains engaged on Irish issues.

Pictured (l-r) Paul Maskey MP, Mark Thompson of Relatives for Justice, and AOH Freedom for all Ireland chair Martin Galvin at the Springhill Massacre victims memorial. Photo by Nuala Purcell

I would recommend this two-part documentary as a contribution to further understanding this period in our history and the relationship between Ireland and its diaspora. My only minor criticisms would be the lack of voices from outside of New York. With the honorable exception of the brilliant and committed Boston-based activist Kathleen Savage, most of the contributions were New York City-based.

As I travel across the states in Chicago, Boston, Hartford, San Fransico, Cleveland, I meet with activists and their families, rightly proud of their work in support of Noraid. This spread was essential in demonstrating the political strength of Noraid beyond New York.

A second criticism would be the absence of a more detailed view of how Sinn Fein in Ireland began to recognise and muster the potential of international opinion, and the US in particular in the peace process and the eventual reunification of Ireland.

While the peace process led to the release of IRA prisoners and fundamental changes in politics across Ireland, US support remains essential in securing Irish unity.

Sinn Féin is now a major political presence in Ireland and across the US political establishment. We now have a peaceful and democratic pathway to unity. All made possible by those who came before us. While much has changed, some things remain. We also still face opposition to change from the Irish and British governments.

The story of Noraid is an example of how action in the US can force change in the positions of US sdministrations and the Irish and British governments.

One of the most insightful comments of the documentary was by musician and former Noraid and NYPD member Chris Byrne. His song, ‘Unrepentant Fenian Bastard’, was the soundtrack for West Belfast in the 1990s. In the documentary, he laments that the Irish diaspora learned and loved Irish culture. Yet the Irish establishment never learned from or loved the diaspora culture. That reflection is worthy of a further documentary.

The director and producers of the two-part documentary have expertly shone a torch on this essential part of history and the role played by Noraid as part of the wider diaspora in shaping the politics of Ireland. There are many more stories out there to be told.

For those able to view it, the documentary is available on RTÉ Player. For those unable, I would recommend Robert Collins’ book, Noraid and the Northern Ireland Troubles 1970-1994, published by Four Courts Press.