Behind West Belfast sits Black Mountain. Hardly a towering elevation it is round with no discernible peak. Yet to locals it is an intimate friend, embracing and mystically comforting, from one’s childhood through to old age. It is loved. It is beautiful and charming whether in bloom with bluebells in spring or snow-capped in winter.

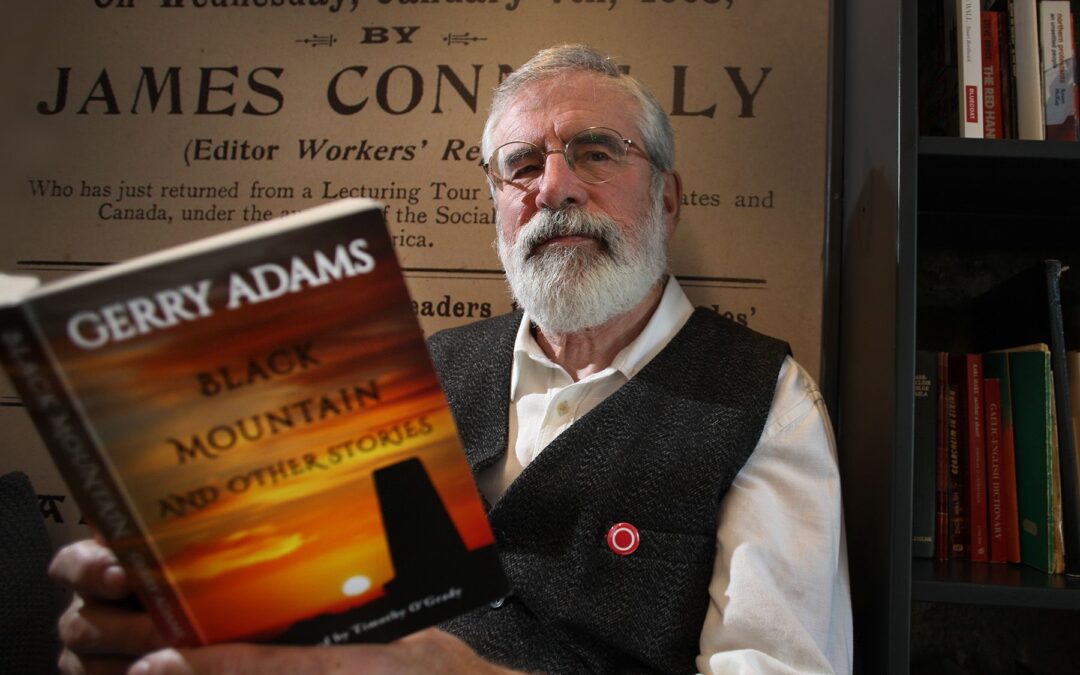

And it is the backdrop to the conversations and musings of many of the characters in Gerry Adams’ new book which has a fine introduction by the writer Tim O’Grady. Adams has written many books, often collaboratively with his amanuensis, the self-effacing Richard McAuley, the majority of the books consisting of political commentary or analyses. But Black Mountain is his work alone and it is dedicated to Richard, his long-suffering, loyal Sancho Panza—I say with affection!

Only two of Adams’s books have been collections of short stories. Fiction is dangerous territory for someone with his profile. Anyone involved in national—indeed, international—politics certainly stick their neck out when they take up the pen to write prose or poetry. They are often resented by successful or struggling scribes as interlopers in an already crowded field. They also present an easy target for journalists out to ridicule or mock, justly or opportunistically. No quarter can be expected from reviewers. If I remember correctly Adams’s The Street and Other Stories was given an ad hominem review in a national newspaper by the late and usually courteous Gerald Barry in an uncharacteristically snide and derisory tone.

But the truth is that Gerry Adams passes the test in relation to the question of literary talent. He observes, he describes, he knows how to maintain suspension, how to surprise, how to make one laugh, how to touch and move one emotionally, writing with authority and confidence, reflecting authentic working-class dialogue which rarely becomes sentimental. He can write from the perspective of an innocent child imagining heaven, in stark contrast to that of a sniper contemplating the life that brought him to this.

His denouements rarely disappoint, even if sometimes anticipated. He never attempts to ingratiate himself with critics and the bookish chattering classes or their rarefied literary salons. He never shies away from his plebeian Ballymurphy and West Belfast roots but gives voice to people’s struggles, domestic, political and moral (a woman mustering the courage to tackle a priest over his one-sided sermons—A Good Confession).

Many of the stories are written in the third person, with some of the first person narratives echoing the real persona, particularly the story, The Mountains of Mourne. It is Christmas 1969 and twenty-one-year old Gerry lands a temporary job working on a drinks delivery lorry with Geordie Mayne, a hard-boiled older man from the Shankill. At first, in bland conversation they dance around politics and religion, then the damn bursts, and the subject of the North bitterly pours forth in hurtful exchanges. Whether they learn anything from each other is a moot point but thanks to a few whiskies they find a sort of brotherhood in singing Beatles’ songs as they climb up through Silent Valley on a dark winter night, the last time they will ever see each other again.

When Gerry Adams was in Cage 11, Long Kesh, and I became editor of Republican News in the summer of 1975, I asked him would he write for the paper. His ‘Brownie’ columns became one of the most popular features of Republican News, avidly read by republican supporters and journalists, and, no doubt, the NIO. In those early writings a rootedness, a discernible unpretentiousness and pronounced humour were all obvious.

When Gerry Adams was in Cage 11, Long Kesh, and I became editor of Republican News in the summer of 1975, I asked him would he write for the paper. His ‘Brownie’ columns became one of the most popular features of Republican News, avidly read by republican supporters and journalists, and, no doubt, the NIO. In those early writings a rootedness, a discernible unpretentiousness and pronounced humour were all obvious.

I prefer novels to short stories. One might think it easy to pen anecdotes of a couple of hundred words but Adams proves himself as a writer in the sustained long, short stories in this volume which never flag. Stories such as The Witness Tree, about a nun looking back many years and thinking of the abusive father who beat her mother and the defining moment when she decided to enter a convent and devote her life to others, including her students. Or Monica, a heart-wrenching contemporary story about Jimmy, a shy and insecure Galway man and his Somali partner, a strong-willed independent woman and political refugee. Their Edenic relationship might be saved by marriage (from which she, a proud woman, flinches) when she faces deportation. Monica is surprised to learn that Jimmy had never been to the North. Back in 1981 her African mother had prayed for Bobby Sands: ‘We identified with him. He made a stand.’ Monica persuades Jimmy to cross the border and go to Milltown Cemetery, after which fate intervenes.

Given his own experiences it is no surprise that imprisonment should feature. In one, The Prisoner, a husband nobly accepts responsibility for a gun uncovered in a search which belongs to his wife, an IRA Volunteer. But he is still beset by worries. ‘Síle was an attractive young woman. He knew she loved him, but what if she met someone else.’

Dear John is about a prisoner serving ten years whose wife leaves him and takes their two children to England, four years into his sentence. During the conflict there were hundreds of wives, girlfriends, husbands and boyfriends doing time with the prisoners. And they didn’t all finish the sentence. Nor were they necessarily set free when the ink in love letters ran dry or when they stopped coming up on visits or if, as often was the case, they found someone else to take the edge off their loneliness. Just to the side of the struggle, out of sight, lay the corpses of marriages and broken relationships shed by the despairing who simply couldn’t take anymore.

The unnamed prisoner unconvincingly tells a comrade that she will be back. But he knows deep down she won’t, and that his life is devastated.

It’s not her fault, okay, he says.

“‘Okay, old friend,’ I said quietly.

“‘You know something else?’ he asked.

“‘What?’

“‘I’m fucked.’ His voice finally broke. ‘Okay?’

“‘Okay,’ I replied.”

A variety of the characters inhabiting the village in the shadow of Black Mountain were christened twice, first at the chapel, then at the corner. So, among many others, we have Big Mick and Wee Mick, The Cube and Wee Root—old boys who philosophise about Gaelic sports, politics and drink. Reading this I was reminded of the Simon and Garfunkel song, Old Friends:

Old friends

Winter companions

The old men

Lost in their overcoats

Waiting for the sunset

The sounds of the city

Sifting through trees

Settle like dust

On the shoulders

Of the old friends

A hilarious story, Up For The Match, features the latter two boyos, bar counters, pulling a stroke with the dole, the funeral for an uncle in Glasgow who is still alive (if indeed he exists), a train journey to Croke Park and the All-Ireland hurling final, and all the little things in between that make life memorable and joyous.

The Cube tells a story within this story as the train crosses the border and heads south.

“‘I remember the time Daithi A drove down for the football final. He had his wee dog with him. He was parking in a side street off Dorset Street and a wee lad came up to him as he was getting out of the car.

“‘Mister,” he said, ‘do you want me to mind your car for a tenner?’

“‘No, son, thank you. I’m gonna leave my wee dog in the car. He’ll bark his head off if anyone goes near it.’

“‘Is that so?” the wee buck said. ‘Can he put out a fire?’”

Touché! Brilliant.

____________________________________________________

Black Mountain and Other Stories by Gerry Adams, published by Brandon, available here and here.