One night in 1956 the Argentinian writer Rodolfo Walsh was in a café in La Plata where he would play chess and talk about literature with friends. Here, six months earlier, when he was also playing chess, there had been a shoot-out at the time of a failed Peronist rebellion which left twenty-seven people dead, eleven of whom were unarmed working-class men, uninvolved in the uprising. They had been taken away by the military to be summarily executed before martial law had been formally declared.

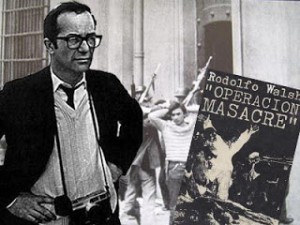

A man approached Walsh in the café and whispered, “One of the executed men is alive.” Walsh immediately investigated the events of that night and interviewed one of the seriously-wounded men who had escaped and gone into hiding. He found and interviewed more survivors. He wrote a series of articles but could only find an underground publisher courageous enough to publish them. Operacion Masacre, an indictment of the military authorities, became a best-seller and changed Walsh’s life.

This week Operation Massacre is being serialized on BBC Radio 4, having recently been translated into English for the first time*. Walsh has been credited with founding ‘investigative journalism’ and of pre-dating by almost a decade the celebrated reportage of the likes of Truman Capote in his ‘seminal’ work In Cold Blood.

This week Operation Massacre is being serialized on BBC Radio 4, having recently been translated into English for the first time*. Walsh has been credited with founding ‘investigative journalism’ and of pre-dating by almost a decade the celebrated reportage of the likes of Truman Capote in his ‘seminal’ work In Cold Blood.

“Both books were considered groundbreaking in their literary treatment of true crimes that the writers had personally investigated and rendered in minute detail,” says Daniella Gitlin who translated Walsh’s book. Of course, the difference is that the culprits Walsh was holding to account were not, like Capote’s, individuals who were under arrest and behind bars, but were part of the military leaders and government who wielded considerable arbitrary power.

Walsh believed in the transformational possibilities of journalism. “Events are what matter these days,” said Walsh, “but rather than write about them, we must make them happen.”

He went on to chronicle the forgotten people of his country, told the stories of those who were tortured, or ‘disappeared’, wrote about a leper community, and the lives of poor farmers. In one piece of investigative journalism, which he published as a story, he interviewed Moori Joenig, the army colonel and necrophiliac who kidnapped and sexually abused Eva Peron’s body.

In his foreword to Operation Massacre Michael Greenberg writes about the Disappeared, those victims of Argentina’s La Guerra Sucia, the Dirty War. It has a resonance and makes uncomfortable reading for an IRA supporter. Though the IRA has been attempting in contrition to recover the remains of the disappeared for the bereft families, the IRA can never make amends. Indeed, it is doubtful if any of the protagonists to the conflict can do justice to the suffering and the dead on whatever side – the sorrow of war bequeathing a far-reaching legacy that no one foresaw or factored.

Greenberg writes in relation to the state’s dirty war, the immunity it has granted itself, the lies it has told, but, again, what he says has a universal relevance: “Prosecutions often occur decades after the crimes. They don’t bring back the dead or change history. But they do affect the future. They lift the cloud of rage and unresolvedness than can hang over the psyche of a country for as long as the perpetrators run free. They force the state, and the general population, to acknowledge the ordeal of their compatriots. They air the truth and relieve an immeasurable weight of psychological repression. Crucially, they vindicate the loved ones of the disappeared who have been consigned to a state of silence and shame.”

Walsh was of Irish extraction, the great grandson of Mary Kelly and Edward Walsh who fled famine and repression in Ireland in the nineteenth century and settled in rural southern Argentina. Walsh married in 1950 and had two daughters but he was a husband who strayed and stayed away a lot as he was smitten with the bug of revolution.

I was first introduced to the writings of Walsh by the Irish journalist and specialist in South America, Michael McCaughan, who spoke at Féile an Phobail many years ago at the Belfast launch of his book, True Crimes – The Life and Times of a Radical Intellectual.

In 1959 Walsh moved to Cuba and helped launch Prensa Latina, an international press agency set up to counter the pro-US bias of international news agencies. It was Walsh, as an amateur cryptologist, who decoded intercepted CIA messages detailing plans for the Bay of Pigs invasion, thus giving Castro crucial warning of the impending aggression. He moved back to Argentina to pursue his writing career but after the death of Che Guevara in 1967 he decided to join the action and after a period in different organisations he joined the Montoneros which were engaged in an armed struggle and he quickly rose through the ranks to become an intelligence officer in charge of infiltration of agents into the army and government.

In 1976 he was dealt a crushing blow when his daughter Vicki was killed whilst engaged in a gun battle with the army. Rather than suffer capture and torture she took the cyanide pill prescribed for all members of the Montoneros. Six months later government forces tracked down Rodolfo Walsh. Twelve agents were sent out to take him alive but he fought back and was shot dead. They took away the corpse, burnt it and dumped it on waste land. Earlier that day he had just posted a letter challenging the authorities.

Military rule ended in 1983, and in 2001 the government of Buenos Aires approved a city ordinance which directed all schools to read out Rodolfo’s “Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta” every year on March 24th, the anniversary of the 1976 coup.

*Operation Massacre by Rodolfo Walsh, £9.99. ISBN 978-1-908699-51-0. For further information contact Ben Yarde-Buller – ben.yb@oldstreetpublishing.co.uk or Tel. 01874 731 222