There have been several lucrative spin-offs for some of those behind the debacle that is Boston College’s Belfast Project, which included former IRA Volunteers being encouraged to incriminate themselves and old comrades on the understanding that their statements (whether true, misremembered or spiteful) would never appear until after they were dead. It is considered by many academic experts to be the worst example in the world of an oral history project. Peter Weiler, former Professor Emeritus of History at Boston College, said the project “tarnished the reputation” of the History Department, and continued: “The project didn’t observe normal academic procedures into projects of oral history. Questions asked were often very leading, and there was no attempt at balance.”

Furthermore, the fiasco has irreparably damaged future attempts to record our past conflict, as it has resulted in the arrests and prosecutions of some of those involved, participants who were given completely false assurances that their recordings would remain safely under lock and key

The key to unlocking it came when Ed Moloney cashed in on the unanticipated deaths of David Ervine and Brendan Hughes to publish Voices From The Grave—which understandably triggered a demand from the family of Jean McConville, a mother kidnapped, shot dead and secretly buried by the IRA, for the PSNI to pursue the leads in an unresolved killing.

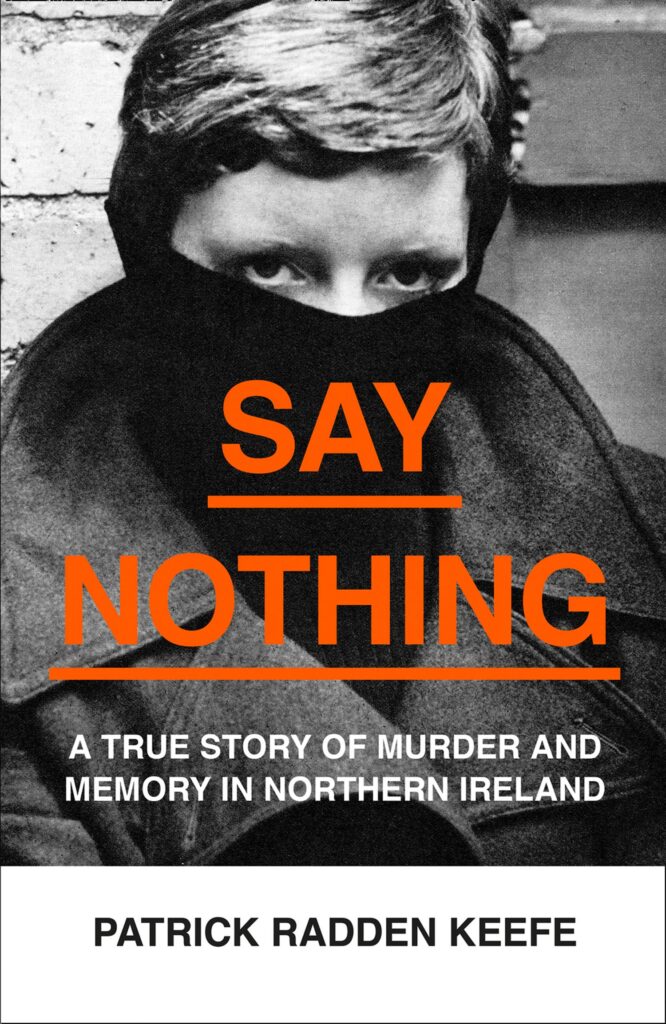

A recent book with a connection to the Boston College Tapes is Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by Patrick Radden Keefe (published by William Collins in Britain and Doubleday in the USA). My friend the author Tim O’Grady (who conducted the oral interviews with veterans from the Tan War period for the highly acclaimed book/film Curious Journey) was recently given it by his daughter on his birthday and after reading it was moved to write something about it. This is what he wrote.

THIS BOOK was first published in 2018 and has been amply lauded by prize committees and numerous well-known journalists, academics and writers in Britain, Ireland and America. Its author, Patrick Radden Keefe, attended Columbia, Cambridge and Yale universities and the London School of Economics and has been in receipt of numerous fellowships and grants. He is a staff writer for the New Yorker.

He is an Irish American, like myself, and like myself his Irishness did not greatly impinge on his childhood. “I found that I did not always relate to the shamrock-and-Guinness clichés and the sentimental attitudes of tribal solidarity,” he writes.

He was, he says, only drawn to write about the conflict in the north of Ireland after reading the New York Times obituary of Dolours Price and its mention of the controversy around the Boston College archive, a project for which she gave lengthy interviews. “I became intrigued,” he writes, “by the idea that an archive of the personal reminiscences of ex-combatants might be so explosive: what was it about these accounts that was so threatening in the present day? In the intertwining lives of Jean McConville, Dolours Price, Brendan Hughes and Gerry Adams, I saw an opportunity to tell a story about how people become radicalized in their uncompromising devotion to a cause, and about how individuals and a whole society make sense of political violence once they have passed through the crucible and finally have time to reflect.”

Say Nothing is divided into three sections of roughly ten chapters each. The first is called “The Clear, Clean, Sheer Thing”, which might be taken to refer to the IRA campaign in the early seventies; the second, “Human Sacrifice”, deals with the 1973 London bomb attacks and the subsequent hunger strikes by four of the bombers, including Dolours Price and her sister Marian; and the third, “A Reckoning”, is mainly taken up with the post-Good Friday Agreement period, with particular concentration on the Boston College tapes.

The book opens with fairly close-focus alternating chapters on the lives of Jean McConville and Dolours Price and broadens gradually to include Brendan Hughes and Gerry Adams, with a single digression to Brigadier Frank Kitson, who brought the lessons he had learned in other British colonial anti-insurgency wars to Ireland.

Given the nature of the subject and the author’s self-declared lack of a personal stake in it, it would seem clear that he can only maintain his authority in telling a story involving diametrically opposed points of view by staying neutral and objective with regard to his own opinions and linguistic choices. This is not to say that he shouldn’t be evocative or colourful or enhancing of drama—such are the tools of his chosen form, which he and others call “narrative non-fiction”—but rather that his personal opinions about the characters and epoch-making life and death events he writes about would inevitably appear embarrassingly trivial and undermining of his role as the teller of the story.

For the first half of the book he manages this well. The account is vivid and deeply absorbing. The reader can feel the human drama of the individuals and the choices they face. You cannot help but feel the extremes of stress that life imposed on Jean McConville, a Protestant who married a Catholic and suffered ostracization from both families, a mother of ten whose husband died when the children were young, leaving her poor, nervous, chain-smoking, pill-taking and inclined to suicide.

The resourcefulness, ingenuity, determination and relentlessness of Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price are truly startling. The heaviness and the viciousness and the cynicism of the British state are exposed.

CROSSES THE LINE

The narrative guard, however, sometimes slips. As early as page twelve he has Dolours Price entering “a cult of martyrdom” when she joins the IRA and calls her wearing of the Easter lily “an intoxicating ritual”. On page fifty-three, she and her comrades indulge in “a fantasy that they were dashing outlaws”. These are unsolicited opinions. They do not come from their subject, or at least are not attributed to her in the notes. They are made to appear general. There is a literature, particularly evident in Roy Foster’s Vivid Faces, which would have IRA Volunteers motivated by family grievance, indoctrination, death wish, loneliness, martyr complex, confusion, fantasy or any other psycho-pathology instead of the simple wish for the British to at last leave their country. Patrick Radden Keefe contributes to it only ambivalently, rather than whole-heartedly, in the first section of his book, but later unequivocally crosses the line separating objectivity from bias.

Having arrived at the Price sisters’ hunger strike in Brixton Prison, he writes, on page 173, “There is a morbid but undeniable [my italics] entertainment in watching a hunger strike unfold… [it’s] a spectacle for rubberneckers, a bit like the Tour de France.” On page 192, referring to the ‘dirty protest’ by the blanket men in Long Kesh, he writes, “…there was something comically grotesque about this whole ordeal—an avant-garde experiment in the theatre of the absurd….” The author, in his Acknowledgements at the end of the book, thanks the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center for the opportunity it gave him to contemplate the writing of it in tranquility by the shores of Lake Como in northern Italy. When I read the sentences quoted above I found it hard to believe that a New Yorker staff writer, used to, one would think, the assiduousness of that magazine’s editors, would write something so starkly ugly, offensive and self-exposing. Perhaps he could not resist the temptation to try to appear worldly. The sentences are fatal to his enterprise, or at least cause it “moral injury”, a term he deploys elsewhere when speaking of the Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome of some of his characters.

It turns out that such examples were harbingers rather than lapses of concentration. Having described Gerry Adams as a gifted and intelligent strategist who endured imprisonment, police beatings and an assassination attempt, and as a “witty, engaging interlocutor with a piercing mind” (page 186), who “commanded respect and loyalty inside the walls of Long Kesh” (page 189), he spends the book’s final 170 pages, at whichever points Gerry Adams is mentioned, being gratuitously snide about him—“homespun whimsy mingled with armed insurrection, cake fairs with a dash of bloodshed” (page 230); “calibrated sophistry” (page 231); “with his smart blazers, carefully trimmed beard and ever-present pipe, Adams had acquired the air of a hip, if slightly pompous public intellectual” (page 232); “there was something slightly comical about this metamorphosis from revolutionary cadre to retail political outfit” (also page 232, referring to Sinn Féin); “well-heeled statesman” (page 268); “gliding along from one photo opportunity to the next” (page 269); “excelled at this type of dissimulation” (page 297). Even when Adams publicly faces the tragedy of sexual abuse in his own family, Radden Keefe refers to “the deft hand of public relations” (page 360). In summary, on page 394, he writes that Gerry Adams “possessed a sociopathic instinct for self-preservation, and there is something chilling about how Adams, secure in his place on the boat, does not cast so much as a backward glance at those comrades, like Hughes, who are left behind.”

This is selective vindictiveness. No one else in the book is subjected to Radden Keefe’s unrelenting and, I would say, unearned disdain. Much of what he says above could have been obviated by a small amount of further thinking or research. It is driven by the idea that Adams betrayed the armed struggle by negotiating the Good Friday Agreement and then jettisoned those who participated in it when it was convenient to do so. Firstly, it is obvious that Adams and others who negotiated the agreement could not have secured it without the consent of at least the majority of the IRA. Secondly, the idea that Adams “does not cast so much as a backward glance” at former comrades is belied by all the commemorations, anniversaries, orations, coffin-bearing, pamphlet-writing and numerous gestures public and private participated in or conducted by him in recognition of IRA veterans. Thirdly, to pin all responsibility for the agreement on Gerry Adams is to misunderstand Sinn Féin in general and the agreement in particular. Sinn Féin is not a top-down organization. It moves collectively. The agreement was negotiated on the republican side by a team of publicly identified individuals of young and veteran republicans, Sinn Féin elected representatives and former prisoners. Radden Keefe would have appeared to have forgotten the research part of his role—or else willfully forsaken it.

Why did he do this? Not because of personal experience. He says himself that the motivating interest for his book was intellectual. Is his disenchantment borrowed? From whom? He writes that the obituary of Dolours Price and its mention of the Boston College tapes set him off on his search. He begins to write about them on page 254, but it becomes clear that before and after this point it is the tapes and the personalities associated with them that are his defining source about republicanism during the period under scrutiny. He appears to cleave closely, even exclusively to them and the views of the conflict and its aftermath they have advanced. As they give themselves to it in the 1970s, as Hughes and Price did, so he will report their experiences objectively; as they grow disillusioned after the Good Friday Agreement, so it seems does he.

LEADING QUESTIONS

The idea for the Boston College project began when Unionist academic [Lord] Paul Bew, a visiting scholar there, suggested to the head of the library at the college, Bob O’Neill, that an oral record of the conflict be made as a resource for future scholars and further suggested that the journalist Ed Moloney, an opponent of Sinn Féin, supervise it. Moloney chose Anthony McIntyre, a former IRA member who had served eighteen years in prison and then obtained a PhD under the supervision of Paul Bew at Queens and who was also an opponent of Sinn Féin, to conduct the interviews with a selective group of republicans. Wilson McArthur, from East Belfast, and also the recipient of a degree from Queens, would interview loyalists. The idea of interviewing members of the RUC was abandoned. It seems there was no thought of interviewing British soldiers. A wealthy Irish American donated $200,000 to the project. Moloney was paid as Project Manager, and McIntyre and McArthur were paid £25,000 per annum.

Radden Keefe writes that “for one reason or another”, McIntyre sought out interviewees hostile to the Good Friday Agreement and to Adams in particular. It is difficult to know if he is feigning surprise or is naïve, for the reason is clearly that Moloney and McIntyre were using the project to advance their agenda. Chief among the republican interviewees are Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price. Richard O’Rawe and Ivor Bell followed. When Bell was eventually arrested and charged in connection with Jean McConville’s death on the basis of his Boston College interview, parts of the tape were played in the court. McConville had been captured by the IRA, who believed her to be an informer, and executed her, hiding the body and informing no one of her death. In the tape, McIntyre can be heard trying to get Bell, through leading questions, to incriminate Gerry Adams. Bell can be heard resisting, or at least prevaricating. The interview stops. McIntyre and Bell have a further conversation off-tape. When the recording resumes McIntyre relentlessly pushes Bell to blame Adams for the death. Bell, rather obliquely, does. As McIntyre led Bell, so it appears he also led Radden Keefe. In the latter case it appears not to have been difficult.

McIntyre and his interview subjects are aggrieved primarily by two things—by Gerry Adams denying he was in the IRA and by the peace process, which they regard as a betrayal of the movement and an invalidation of their personal sacrifice. These grievances drive the latter part of the book. Those who hold them are of course free to do so. But Radden Keefe neither questions these views nor seeks others. He rather appears to assume them as his own. I know nothing of Gerry Adams’ involvement in the IRA, but I do know that McIntyre, Hughes, O’Rawe and Price all served time for IRA-related actions but that Gerry Adams has a conviction only for escaping from prison, so that if he were to say he was in the IRA he would spend much of the rest of his life in courtrooms or custody. And the alternative to the peace process? War without end? Or something else? To what end? Are they searching for the comfort articulated by Patrick Pearse – “Whatever soul searchings there may be among Irish political parties now or hereafter, we go in the calm certitude of having done the clear, clean, sheer thing. We have the strength of mind of those who never compromise”?

Or perhaps they have an actual plan? We won’t know from this book.

The Boston College project was a dangerous fiasco. Had it not been exposed, the future scholars it was intended for would be left with the impression that the conflict in Ireland was between loyalist paramilitaries and republicans (McIntyre was given a life sentence for the killing of a loyalist, Kenneth Lenaghan) who were set up by their own leadership. The police and British Army, being absent, were presumably honest brokers keeping irrational medievally-minded factions apart, rather than conductors of a colonial war. A distorted and minority view is thus placed in a vault and given the veneer of truth by a supposedly respectable and dispassionate academic institution. It is a spectacular example of leveraging.

Ed Moloney, having promised the interviewees that not only their testimonies but the project itself would remain a secret until all of them were dead, blew its cover upon the deaths of David Ervine, a loyalist, and Brendan Hughes by publishing a book based on their interview material called Voices from the Grave. Both before and after publication he blocked scholars and writers from access to the tapes. He discouraged Richard O’Rawe from writing his own book. It is difficult not to conclude that he was trying to eliminate the competition.

Predictably, when the police in the north of Ireland learned of the existence of the tapes they believed them to be a free evidential treasure trove and successfully went after them with subpoenas, hoping, as Radden Keefe says, to bring down their principal nemesis, Gerry Adams. When McIntyre complained that only republicans were being targeted the police did not desist but went after a loyalist as well. Wounds were opened, lawyers drew fees, Jean McConville’s children’s questions remained unanswered and an old man with dementia (Ivor Bell) was brought before the court and eventually let go. The seemingly infallible Boston College archivists misplaced their codes. They were disowned by their own History Department. Eventually they gave up. They returned to Richard O’Rawe his interview material. He is reported on page 403 to have burned it in his fireplace while he drank a glass of Bordeaux. Ed Moloney, however, having collected his fee and secured his book contract, went on to release his Netflix film, I, Dolours, based on his interview with Dolours Price.

Several commentators have referred to this book as a “crime story” or “whodunit”. Radden Keefe in an interview called it a “murder mystery”. A reviewer for The Times said she was bored by “Northern Ireland’s past” until she read it. Such words are normally reserved for entertainments, not factual stories about traumatized lives and agonizing deaths. The crime in question is the killing of Jean McConville. But little about her death is definitively established. Her children’s story is that she was questioned by the IRA and then taken away on consecutive nights and that the reason for this was that she had once put a pillow under the head of a wounded British soldier, but it appears to be contradicted by police and British Army records. Ivor Bell, Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price all believe her to have been a paid informer, but proof, if it exists, is not put forward in the book and is also disputed by officials.

Ed Moloney presses Dolours Price into an admission that she was part of Jean McConville’s execution detail, along with the long-deceased Pat McClure and an unnamed Volunteer. Anthony McIntyre tells Radden Keefe he knows the identity of this third person and won’t tell, but lets it be known that it was someone who once declined an invitation to be Gerry Adams’ driver. Radden Keefe then notices in the transcript of an interview with Dolours Price that her sister Marian had once turned down the chance to be Gerry Adams’ driver. He attempts to build much drama around this discovery. Some writers may have demurred at this point. It is a serious and dangerous charge. The evidence is hearsay and not definitive even if it is accepted as true, as it could be coincidence. Presumably others turned down the invitation to be Gerry Adams’ driver given that he has been a target of assassination for most of his life. Marian Price lives in Belfast, as do several of the McConville children. But Radden Keefe is writing a “murder mystery” and feels he may have solved it. In the jargon of such books, he puts the finger on Marian Price. One also wonders about the motives of McIntyre in passing this information from an interview he had sworn to keep secret. It all happened just short of half a century ago.

Say Nothing has won the Orwell Prize for Political Writing, the National Book Critics’ Circle Award and the Arthur Ross prize from the Council on Foreign Relations; it was called the “#1 Nonfiction Book of the Year” by Time, selected by Barak Obama as his favourite book of 2019 and declared by Entertainment Weekly to be among the ten best non-fiction books of its decade. It was also a finalist for the Christopher Ewart-Biggs prize, dedicated to “peace and reconciliation in Ireland” and “a greater understanding between the peoples of Britain and Ireland”, though it appears to advance the views of those who believe the war should never have stopped. It is called an example of “narrative non-fiction”. There seems to be an attached sense that this is something new. Is it different from Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722? Possibly, as Defoe’s account is first person. But it would be difficult to think of it different formally from what Tom Wolfe collected in his anthology The New Journalism, published in 1973. Nevertheless, courses in Narrative Non-Fiction no doubt have appeared or will appear in Literature and Creative Writing programmes, with Say Nothing on the syllabus.

But there is something deeper, more universal and more important going on in this book than the grievances of those who took part in the Boston College project. Radden Keefe read Dolours Price’s obituary and sensed in it something about the hazards of remembering war. For the book’s epigraph he chooses Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” The latter is often greatly worse than the former. Say Nothing demonstrates this to be the case with Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price. Among British soldiers, Irish police, loyalists and republicans are many who have fallen to addictions, paranoia, despair and suicide.

It is not only the witnessing and being victim of violent acts, but also their inflicting that contributes to this effect. “Volunteers didn’t only die,” Dolours Price says in the book. “Volunteers had to kill as well.” And when you kill, it has been pointed out to me, “you can never return to who you were before.” Chief among the victims described are the McConville children. They lost their father, their mother disappeared, they were feral in Divis Flats until they were moved through a succession of Catholic institutions, in some cases staffed by sadists and paedophiles, and were then released into the world, where they learned fragment by fragment what happened to their mother. They still don’t know all of it. The whole society is intermittently consumed by the traumatized remembering of these things. Campaigns are launched, police investigate, the government conducts inquiries which last years and often fail to produce significant results, and criminal cases are heard to which great-grandfathers are brought to account for things that happened when they were teenagers. Behind this book is a non-ostentatious flood of pity for those thus suffering.

The war in Ireland like all wars had its examples of heroism, uncanny endurance, accidents and barbarisms. Most who participated in it thought they were doing what they had to do. The society does not in all cases find itself able to leap free from these events. The past keeps calling for a reckoning. This is obviously understandable, particularly for those who have not received answers, apologies or requests for forgiveness regarding their dead. But neurologists have demonstrated that you cannot remember unless you can also forget. It is equally true that total forgetfulness is itself a disease. It has further been demonstrated that acceptance and forgiveness are not only saintly, but also liberating. All of these qualities combine in an individual as a process rather than as something static, and perhaps also in societies. Some loyalists and some republicans sense the ameliorative effects of this. They would appear to be open to a more effective truth and reconciliation forum than was established in South Africa at the end of apartheid. This is less true of the British government. It seems to them to be far away, their faith is bad, they have little to gain and much to lose as their crimes reach to the top of their hierarchy, 10 Downing Street. But the negotiators of the Good Friday Agreement fashioned ingenious devices and the prizes are great—the peace of the dead, the mental health of the living and the fashioning of a new and agreed Ireland.

Timothy O’Grady

Timothy O’Grady has written for numerous publications in Britain, Ireland and the United States and is the author of three novels and four works of non-fiction. His most recent book is Children of Las Vegas.