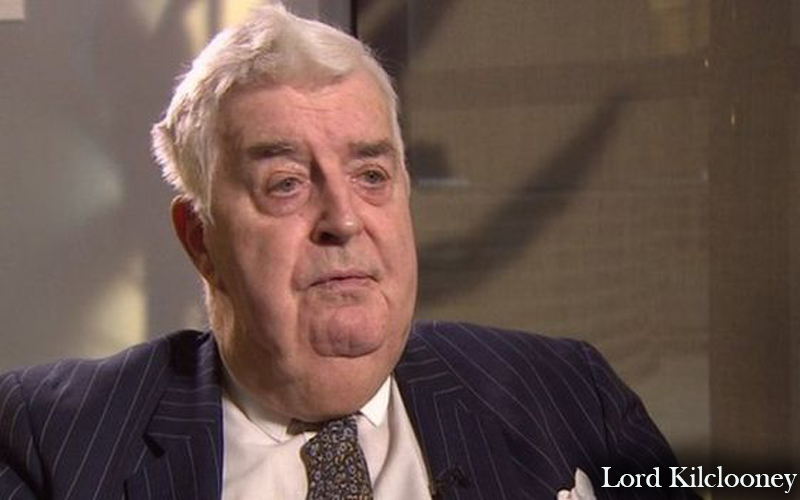

Today’s Irish News carries a story, headlined “Lord Kilclooney says nationalists ‘are not equal’ to unionists”. Taylor told the newspaper, that a unionist majority meant nationalists could not claim equality – though they were entitled to equality of opportunity. Kilclooney is being quite consistent in his supremacist attitude. Here is a feature I wrote seventeen years ago and which appears in my book Rebel Columns.

UNIONISM MISUNDERSTOOD – SOME CLARIFICATIONS

The Beliefs of Mahatma Taylor

During the negotiations before the signing of the Belfast Agreement on Good Friday 1998, John Taylor, said he wouldn’t touch Senator George Mitchell’s proposals for a settlement with ‘a forty foot barge pole’, though he did stand by his party leader, David Trimble. Here are some of the things that John did touch on, during an illustrious political career.

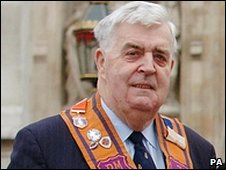

John Taylor, former MP, European MP, and deputy leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, was Home Affairs Minister at Stormont at the time of Bloody Sunday and was later shot and seriously wounded by the Official IRA. A staunch Orangeman, and a former member of the extreme European Right Group (led by the French National Front’s Jean Marie Le Pen), he has now retired from politics to concentrate on his business and property interests. [In June 2001 John Taylor became Lord Kilclooney, and in the Assembly elections of November 2003 he became a member for Strangford.]

John Taylor, former MP, European MP, and deputy leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, was Home Affairs Minister at Stormont at the time of Bloody Sunday and was later shot and seriously wounded by the Official IRA. A staunch Orangeman, and a former member of the extreme European Right Group (led by the French National Front’s Jean Marie Le Pen), he has now retired from politics to concentrate on his business and property interests. [In June 2001 John Taylor became Lord Kilclooney, and in the Assembly elections of November 2003 he became a member for Strangford.]

A short selection of his quotes over the past thirty years usefully reveals something of his attitude to violence and democracy.

On the belief that ‘one-man-one-vote’ should be the sole basis of the franchise for local government elections in 1968 he said: “Nothing could be further from the truth. Both in the republic and Britain individual voters are given many additional votes on the basis of property ownership.”

In March 1970 after a UVF bomb attack on the home of Austin Currie he said that the attack would be to Mr Currie’s “political advantage”.

Responding to the arrest of a man carrying a hurley after coming out of the Falls Park with his wife and kids in June 1971, he said: “I am not surprised that the army should take such action when one recalls the provocative manner in which hurleys were used in connection with an IRA funeral in the city.”

In July 1971 he defended the British army killings of two innocent men, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie: “I would defend without hesitation the action taken by the army authorities in the city of Londonderry against subversives during the past two weeks where it was necessary to shoot to kill. It may be necessary to shoot even more in the coming months.”

On the issue of ‘decommissioning’ (as it was then not called), September 1972, he told a Vanguard rally: “There is far too much talk about the handing in of guns… The time has come when the loyalists of Ulster must not give in to the campaign by Harold Wilson and the SDLP to disarm the law-abiding citizens of this province.”

On the use of violence, he told another Vanguard rally in Tobermore, in October 1972: “We should make it clear that force means death and fighting, and whoever gets in our way, whether republicans or those sent by the British government, there would be killings.”

In July 1974 he called for the formation of a Home Guard: “I believe that it will be armed, that it will be some 20,000 strong, that it will defeat the IRA and that it will be a force born of the people and with the people. It will be a force which London will learn to respect, a force which loyalist politicians will support with or without London government legislation.”

On nurses from the south working in hospitals in the north he had this to say in December 1984: “Too many jobs are being given to people from the republic and many of them probably sympathise with the killing campaign of the IRA.”

In January 1989 he criticised the Dublin government after its decision to award £500,000 to the Society of St. Vincent de Paul (clearly mistaking it for the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, the dissident, breakaway IRA faction).

On the Catholics (Roman ones) you see in the street, he said in September 1991: “One out of every three Roman Catholics one meets is either a supporter of murder or, worse still, a murderer.”

On the GAA: “I can understand why loyalist paramilitaries would attack the GAA as it is perceived as a political and divisive force.”

In September 1993 he spoke out about the sectarian killings of Catholics: “There is in particular amongst the Catholic community now increasing fear of paramilitary activities… And, in a perverse way, this is something which may be helpful because they are now beginning to appreciate more clearly the fear that has existed within the Protestant community for the past twenty years…”

IT is quite obvious from the above that John Taylor has no problems with guns – provided they are in the hands of loyalists, provided they are used to maintain and protect the union. It is also obvious from his attitude to the negotiations leading up to the Good Friday Agreement and his stance since then that he has never favoured reform or compromise. Indeed, he was delighted when the Assembly and all-Ireland bodies were suspended by Peter Mandelson and boasted that unionists were happy to be back to direct rule with no Irish frills attached.

His views, unfortunately, probably represent those of more than one half of the unionist people – ‘the British presence’, as Billy Hutchinson prefers them to be called. The reluctance of a majority of unionists or their representatives to engage with nationalists on an equal footing is assumed as being acceptable and is glossed over by the British government and the media. British governments have also used it as a pretext for refusing to redress the injustices that were institutionalised as a result of partition.

To paraphrase Jim Molyneaux, the IRA ceasefire represents the greatest threat to the union in seventy years. Reactionary unionism understands that. It needs a scapegoat. It needs cover.

It would prefer the IRA back at war.