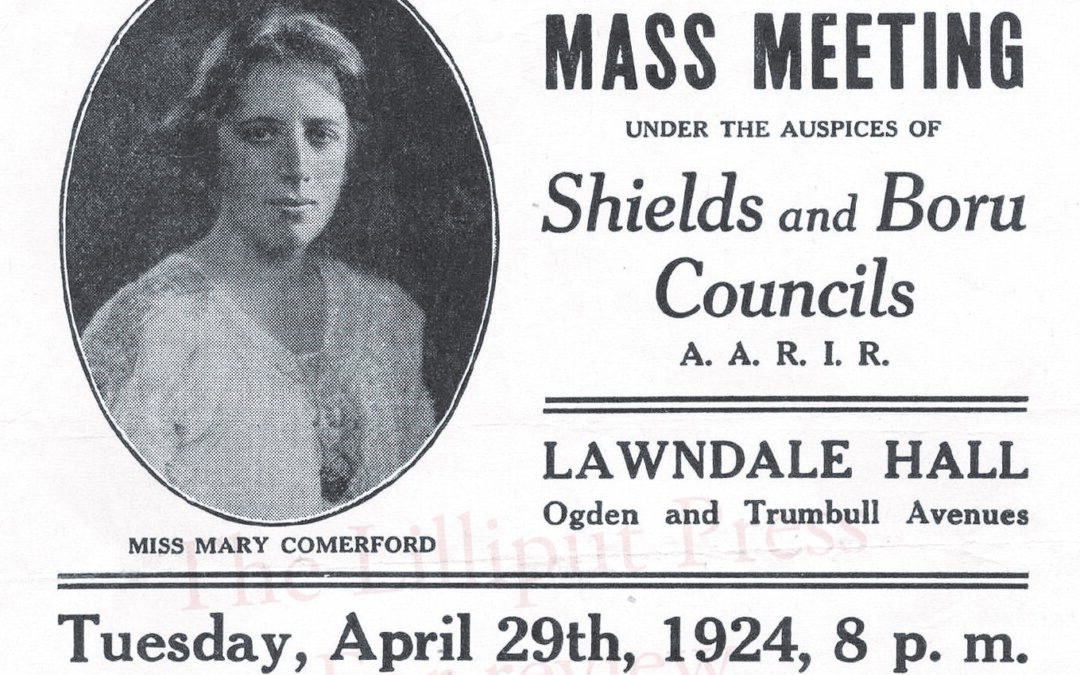

Joe Dwyer, Sinn Féin’s representative in Britain, based in the party’s London Office, reviews veteran republican Maire comerford’s memoir, edited by Hilary Dully.*

I first discovered Máire Comerford when I was probably fifteen or sixteen and first watched Kenneth Griffith’s superb Curious Journey documentary (based on the book Curious Journey which is being reissued by Greenisland Press in April 2022).

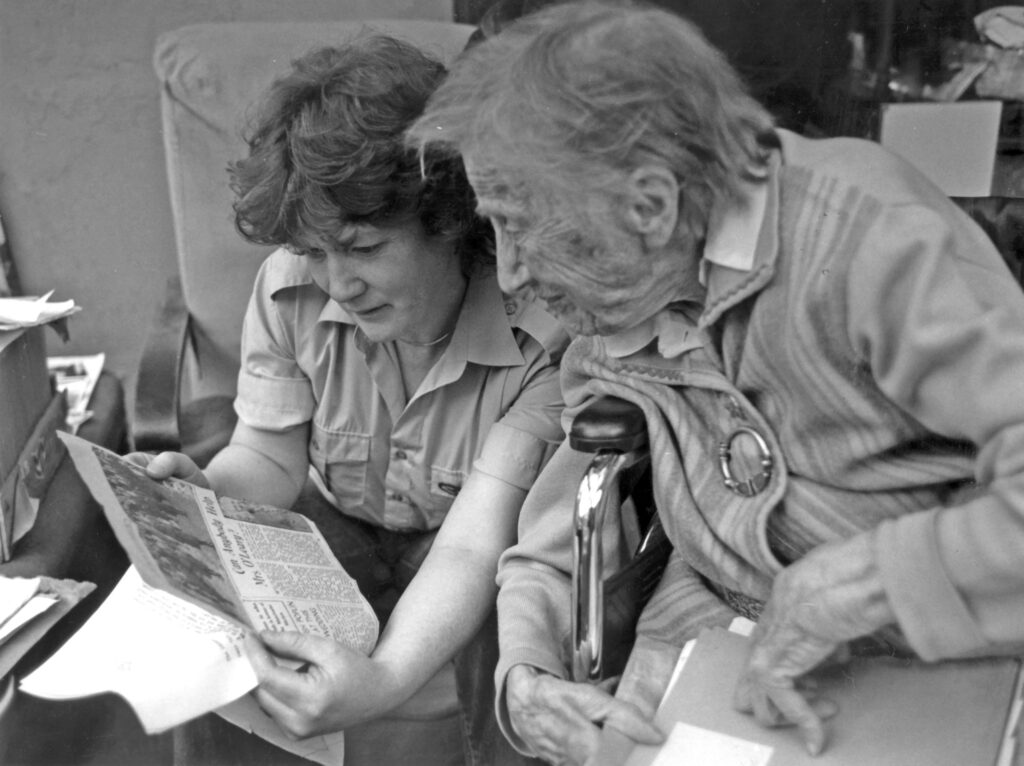

The film actually opens with Máire. A smiling, little old lady sat in a big chair, eyes near closed with the weight of years. Indeed, it is almost jarring when Griffith’s voiceover introduces her as: ‘Patriot and activist in the Irish Republican Army’. The character presented on screen is far from the typical depiction of such a description. But this is why Comerford remains a fascinating figure.

Máire Comerford is arguably emblematic of the hundreds, if not thousands, of activists – principally women – who were written out of the history of the Tan War. Ordinary people who were caught up in extraordinary times.

As she summaries herself, ‘I was never a cog in the official government machine of this period, or a candidate to be a cog. Ireland had thousands of girls and boys like me at that time. The most that I can claim is that I tried to be a drop of oil helping to make things work when the chance to do so arose, as it did in those times, daily and nightly.’

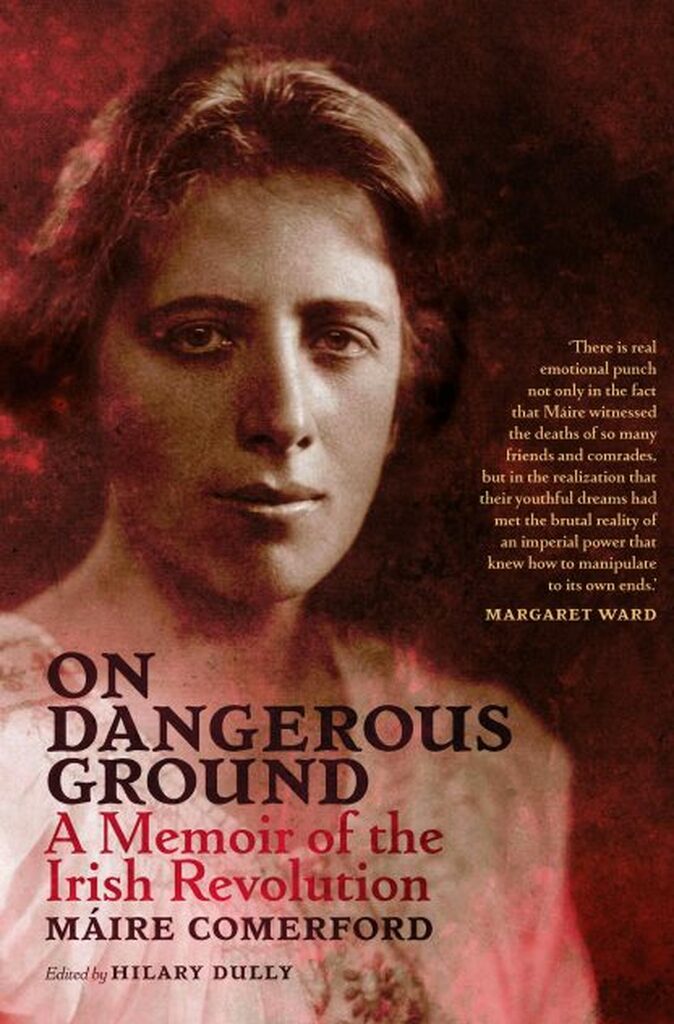

As such, the long overdue publication of her memoirs is to be celebrated and those behind the publication, especially the editor Hilary Dully, commended.

While Uinseann MacEoin’s invaluable Survivors dedicated a chapter to Comerford, On Dangerous Ground finally provides us with a fuller, clearer understanding of the woman. Her actions, her perspective, and – later on – her reflections on events make for fascinating reading.

Her reflections, written in the autumn of her life, are full with all the exuberance and excitement of youth. The book deals with the daily operation of revolution. Hers is a story of cycling round Dublin, carrying dispatches, eavesdropping on auxiliaries, and mobilising women of all social classes and backgrounds.

The reader follows Máire as she crosses paths with various famed republican leaders. Personalities like Countess Markievicz, Michael Collins, Éamon de Valera, and Liam Mellows. Figures who can often become merely stale names of history, but who Máire manages to capture and bring back to life through a wry observation or curious anecdote.

Her generosity of spirit shines throughout the book and offers example to republicans in our own time.

She is quick to recognise the sincerity of many of her political opponents. And also, the obstinacy of some on her own side. For example, while she holds true to her republican convictions, she is also prepared to acknowledge that those she witnessed enlisting for the First World War were motivated by honest, if misled, patriotism.

She often exhibits a fondness for old foes. Despite having stood on different sides during the civil war, she kept a friendship with Mabel Fitzgerald (wife of Desmond Fitzgerald who took the pro-Treaty side) and later met her regularly over cups of coffee in Bewley’s Café.

In possibly the most engrossing section of the book, the civil war period, she laments the split but ultimately concludes that such a divide was unavoidable. Writing from the perspective of subsequent decades, she notes, ‘When I ponder on these gifted men now, I wonder at the length of time during which they held together as a team, more than I do that they split in the end.’

The memoir shows no hint or shred of self-aggrandisement or praise. Indeed, Máire is at pains throughout to stress that she did nothing exceptional. Repeatedly emphasising the contribution of others and the collective nature of the republican movement.

Rather than individuals, her resentment is most keenly directed towards the structural fault-lines within the republican movement. The treatment of women receives particular attention.

As she reflects, ‘It never occurred to me to doubt that the Republican government, when we put it in power, would do justice to both sexes equally and, of course, to all of the people.’ Such faith was soon disabused on 2 March 1922, when the Dáil rejected Kate O’Callaghan’s motion seeking the admission of Irish women to the parliamentary franchise on the same terms as men.

As Comerford remarks, ‘It is my firm conviction that the public welfare can never be judged, or good decisions arrived at, except from the standpoint of equal partnership between the sexes. These remarks are also addressed to organisations which give lip service to Women’s rights, but fail in performance.”

In many respects the memoir is a tribute to the many women also betrayed by the ‘four glorious years’. The book is rife with names that should be better known to republicans today. Names no doubt worthy of their own biographies; Aileen K’Eogh, Lily O’Brennan, Áine Ceant, Anna O’Rahilly, Maire Perolz, Charlotte Despard, Gobnait Ní Bhruadair, Mary Colum, Rosamond Jacob, Moya Llewelyn Davies, Patricia Hoey, Anna ‘Miss Fitz’ Kelly, Lou Kennedy, Dulcibella Barton, Maria Curran, Mary Hoyne, Mary Moran, Máire Rigney, Eithne Coyle, Eileen McGrane, Linda Kearns, Kate Crowley, Madge and Lilly Cotter, Geraldine Dillon, Maa Woods, Eilís Ní Riain, Fiona Plunkett, Emily Valentine, Margaret McElroy, Nell Humphreys, Una Gorden, Madge Clifford, Bridie Clyne, Dorothy Price, Kathleen Lynn, Caitlin Brugha, Maura O’Connell, Linda and Kathleen Barry, Maev Phelan, Sighle Humphreys, and Josephine O’Donell. To name a few, but still not enough.

In fact, Máire is equally determined to pay tribute to those she cannot name. Such as the woman waiting on the sidewalk ever ready to catch a smoking revolver or an undischarged bomb. Or those who stood behind doors that opened at a crucial moment and closed just as quietly. The unnamed public servants and administrators who carried out the menial and operational functions of the Dáil, daily. Or the unknown comrades who carried on the fight into later years.

The book is packed with excellent titbits that only someone who lived through events can tell. The kind of details that bring history to life. Such as, how the flare of the photographer’s camera, during the sitting of the First Dáil, was mistaken by some for an explosion. Or how difficult it was to match Liam Mellows’ moustache when dying his hair to go ‘on the run’. Or how a long skirt can best hide a long rifle.

Comerford’s life bridged the Tan War with the most recent phase of struggle in the north. She kept the faith and was said to be a mainstay at local republican commemorations. As late as the 1970s, her dog was affectionately called ‘Shinner’ and her support for republican prisoners is well recorded.

By all accounts, she remained a committed republican until her death in December 1982. Her funeral oration was delivered by Danny Morrison, then Sinn Féin Director of Publicity.

On Dangerous Ground is a brilliant memoir and one that all republicans should pick-up. It deserves its place on a bookshelf alongside Breen’s My Fight For Irish Freedom or Barry’s Guerrilla Days in Ireland. In fact, it goes beyond most memoirs of this period, providing a more rounded picture of the republican movement as a whole and the dynamics within it. It restores the role of women and gives tribute to those drops of oil that helped the cog turn.

Finally, Máire issues a challenge to the reader of today. Her struggle remained incomplete at the time of writing – and is still incomplete to this day.

As she states, ‘People refer to the independence of Ireland as if freedom has been won. But think of it this way – if someone is handcuffed to another person, are they free? The partition of our island has made it impossible for our nation to grow and mature, as modern democratic states should be free to do.’

It is a truth that still stands and a challenge to us all. ‘What would Máire do?’ wouldn’t be the worst maxim in these times.

*On Dangerous Ground – a Memoir of the Irish Revolution by Máire Comerford, edited by Hilary Dully, is published by Lilliput Press and can be bought at An Fhuiseog, Belfast and at the Sinn Fein bookshop, Dublin