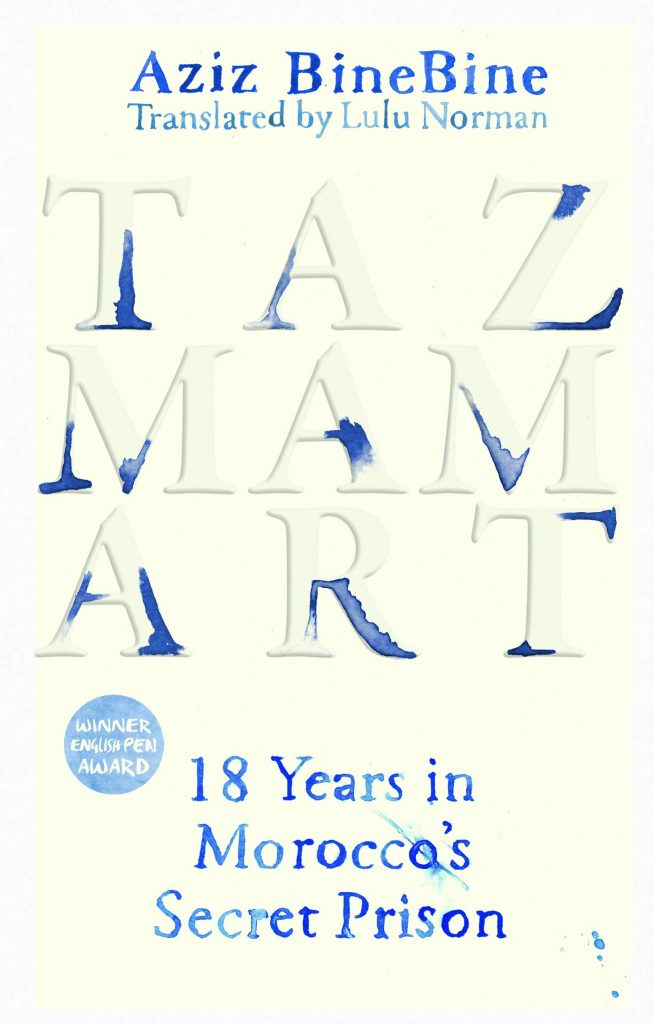

My review of Moroccan Aziz BineBine’s biography about his eighteen years of torture in the dungeons of Tazmamart was published in last Saturday’s Irish Examiner. Tazmamart was translated from the French by Lulu Norman and is published by Haus – pp. 190. £14.99

-oo0oo-

Kacem had chronic tonsillitis and couldn’t eat or drink. When everyone was asleep in the block he attempted to remove his tonsils using a bit of purloined corrugated iron that he had sharpened into a blade. He put his finger to the back of his throat to find the swollen glands and began his incisions.

The others awoke, heard stifled groans, moaning and gurgling – but these were normal sounds in this nightmarish dungeon. In the morning Kacem did not appear at his cell door for the daily ration of bread and water. The others called to him. For three days he lay delirious with fever and fell into a coma. The guards dug a hole in the yard, dragged out the body, sprinkled it with quicklime and buried it without ceremony. Such interments became the norm.

Prisoner Kanat was the interpreter of their dreams. Unlike the others he didn’t devour his bread immediately but stockpiled it in a bag which became infested by cockroaches. They laid their eggs and deposited their excrement in the bag. Despite his comrades’ warnings he was so hunger he would eat the soiled bread which brought on fevers and delirium and eventually poisoned him to death. Others died of hypothermia in the glacial winters of Tazmamart prison. Others went insane.

In the summer, snakes, tarantulas and various lizards would invade the cells. But the worse were the scorpions. The only light that penetrated the men’s cells was through three holes near the top of the door. So heightened had their hearing become that they could tell the differences between a cockroach falling off the wall and the tiny thud of a scorpion.

Thami Abounssi heard a scorpion fall and spent all night tracking its sounds, wrapping himself in his blanket and remaining stock still when it came near. In the morning when his cell door was opened and there was a little light, he stamped on the scorpion but missed its tail and it stung him. He went through hell for forty-eight hours enduring the torment of its poison.

Aziz BineBine’s story of eighteen years in the secret desert prison of Tazmamart was brilliantly fictionalised in 2001 in The Silence of Absence, the Blinding Absence of Life by Tahar Ben Jelloun. But in this eloquent memoir he tells it in his own words and it is even more powerful, even more riveting.

BineBine’s father, an Islamic scholar, was an advisor/confidante to the despotic King Hassan II of Morocco. Aziz became a young army officer – though he’d thought of becoming a journalist or a filmmaker. In July 1971 BineBine and other soldiers were led to believe that the king was in danger from a coup. Their convoy was ordered to the summer palace in Skhirat where the king was holding a birthday party. In fact, the soldiers were unwittingly being used by disgruntled, military officers aiming to assassinate the king. There was chaos and over one hundred people were massacred in the failed putsch.

The leaders were arrested and summarily executed. Although innocent, BineBine and others were given lengthy prison sentences – which were increased after another attempted coup in 1972. They were then ‘disappeared’. All contact with the outside world ceased and they were imprisoned in dungeons below a hangar in the desert.

His cell was two metres by three. It had a block of cement for a bed and a squat toilet from which emanated the stench of fetid air from the sewer. After a storm the cells became ankle-deep in raw sewage for days on end. They were given two threadbare blankets that dated from1936. One prisoner through a peep in his door saw the guards clean the cooking pot with the same scrubbing brush used to clean the floor; saw them fish out dead cockroaches, a rat, a scorpion.

“I was standing in what appeared my grave… I must forget the world outside… my cell was my universe; my companions in misfortune my only society; culture and faith my only wealth.”

The drinking water was so polluted that many died of dysentery. Meals never varied: a small bread roll, boiled chickpeas and some pasta. They washed using their own urine because it was sterile. When a comrade died they also begged the guards for his rags, it was so cold in the prison.

As well as being an observant Muslim, BineBine became a storyteller to his fellow prisoners, none of whom could see each other. He delivered a course on philosophy and he entertained them by retelling novels he had read by French writers, the Russian greats and stories from early twentieth century North American fiction.

“One day a comrade sent me a bit of bread. This was cataclysmic. I couldn’t get over it, a starving man sharing his meagre fare… I had to choke back sobs.” BineBine said it was like receiving the Nobel Prize.

The book is a homage to the men who died of hunger, cold, parasites and inertia. He tells the story of their suffering, their joys, hopes and regrets. “We were never sad when a comrade departed; we were relieved for him. We responded to death by giving thanks as the Qur’an taught us.”

There was comradeship – but BineBine also describes one episode of which he was subsequently ashamed. In the next cell was Captain Bendourou, his former battalion commander. Each prisoner had confided his personal story, his weak points and strong suits, and in return there was respect and courteousness. BineBine had told them about his father, a friend of the king, denouncing him. So, Bendourou set out to humiliate him and shouted out the door one night that he was “a bastard.”

“You know, and everyone here knows, you’re just a bastard! Your father officially disowned you in front of the whole country.”

In retaliation, and wilfully, BineBine shouted, “Cuckold!” and let it slowly sink in. Then repeated: “Cuckold, you’re the father of a bastard,” then, for all to hear, shouted out the date the child had been fathered and the date born. He knew that his dagger struck to the heart of Bendourou, who fell silent, who fell fatally ill.

“It was the longest, most brutal and cruellest argument that took place within the walls of Block 2… I was not proud of myself.”

It was around this time that the publication of Notre ami le roi (Our Friend the King) by campaigning French journalist Gilles Perrault alerted the world to the existence of the secret prison. International pressure piled on the regime. Conditions changed, food improved, nurses were assigned and medicine distributed for the first time. Into the eighteenth year of his imprisonment BineBine and his comrades were “pardoned” by the king.

We were let out, says BineBine, “but without our health, our youth or our innocence.”

This is an incredible memoir, a story of the indomitability of the human spirit over adversity, an epic story of survival.