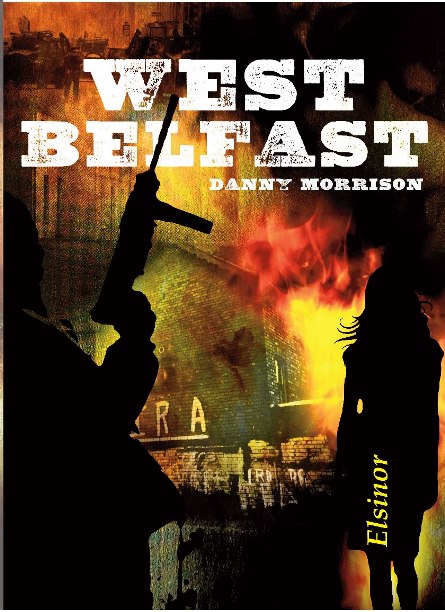

Continuing on in my novel, West Belfast, which deals with the rise of the IRA post-August 1969, here is Chapter Eight, titled, The Honeymoon Period.

“You’re wrong!” said Dominic. “You’ve got it entirely wrong.”

The men were in the upstairs bedroom of a supporter’s house. John was invited along to talk about smuggling and what he could do for the Auxiliaries, a branch of the IRA which he had joined in the aftermath of the pogroms.

“Dominic, listen. You see for yourself. The people are giving the British Army tea and sandwiches. I had to stop my own bloody wife from cooking for them. The wee girls of the area are even going to dances and discos in the mill. Generally, the British are welcomed and we have to take that on board. Without them on the fifteenth and sixteenth of August the rest of the Falls would have been burned out.”

“That’s nonsense. We would have been okay from then onwards. Bits of gear were starting to arrive from the Free State. The soldiers weren’t sent here to protect the people but to protect the Stormont government. Listen carefully to what General Freeland said about the soldiers and the community enjoying a ‘honeymoon period’. He’s not a stupid man. They’ll protect us, then they’ll police us, then they’ll persecute us and it’ll end in divorce and funerals. You’re forgetting what you told us down the years about ‘British imperialism’ being ultimately responsible for our plight. Besides, by the fifteenth we had started a rumour that we were gonna invade the Shankill because of what they’d done the night before. That stopped them.”

“Will you let me finish? Okay?”

“Okay. Go ahead. I’ve heard it all before.”

John sat and listened. He didn’t know what to make of these arguments amongst old comrades disputing the way forward. Others confided in him that there was no faith in the leadership. They had let people down and they were going to be ousted.

“We are in a very strong position. The B Specials are going to be phased out and the talk is that the RUC is to be disarmed. With the spotlight on this place we can get all the reforms we want pushed through.”

“That’s fuckin’ nonsense,” said Dominic. “Stormont hasn’t been suspended, the unionists are still in control. There’s no chance of the RUC being disarmed because if they were unarmed there wouldn’t be a unionist in the North prepared to join such a Boy Scouts organisation. We are in a prime position but for different reasons. For 50 years the British have been able to ignore this place, they’ve internalised it and it’s been forgotten about. Now we’ve got British soldiers back on the streets . . . British soldiers! Here is ‘British imperialism’ confronting us, even though it’s in a peace-keeping guise. We should get organised and get stuck into them.”

“Same old dreaming. Same old dreaming that’s cost us dearly down the years. No strategic thinking. All emotion.”

“I fuckin’ resent that. I wasn’t emotional when your brother was shot and I pulled him to safety, was I?”

“I didn’t mean that. Tá brón orm. But let’s go through it. First, the soldiers are popular. Second, we still haven’t enough arms even to properly defend the areas. Third, there’s plenty of people supporting us whilst we defend our own areas but would soon turn on us if we turned on the soldiers. Fourth, we haven’t the right kind of equipment. Fifth, we’ve no money. Sixth, the British Army is very professional and would steamroll us in about a week. Seventh, we’d lose sympathy, I mean international sympathy and right now the whole world is behind us. Eight, do you think the unionists would take it all lying down? You saw what they did because we wanted one man, one vote. Nine … for Christ’s sake the reasons are endless and you want to get stuck into the British Army! Everything is against what you say. Besides, the leadership is opposed to going down that road and that’s that,” he said, attempting to conclude the discussion.

“Dominic’s right.” The next speaker was an old republican who had been interned in the 1940s for a time, and again in the 1950s. He was a small man, a handsome man yet he had remained a bachelor.

“We’ve got the British by the balls,” he said, taking a long draw of his cigarette. “Nobody can persuade me that they’re here to protect the Catholic community. I’ve prayed for this day all my life. If we miss this opportunity we may forget about everything. You say the soldiers are popular. Not in Clonard they’re not. Those who are supporting them will get stung, sooner or later. It’s in the nature of this army, wherever they’ve been, wherever they go. They will take this hospitality for granted, come to take the people who show kindness to strangers for fools. Guns and money? We’ll get guns and money. All those people who had to leave here because there was no work or who suffered discrimination? They’ll arm us, from the States, from Australia, the Irish around the world who despise the British and what they have done to Ireland. For that corrupt, stinking, sectarian government up at Stormont, it will be a case of the chickens coming home to roost. The sight of all those refugees having to move south and live in camps will result in guns and bullets and explosives to our cause. Regarding support, it’ll be the people around here, it’ll be the people of Ardoyne, the New Lodge, the Strand, the Bogside and Creggan who’ll support us. Working-class people, the ones who always do all the suffering and sacrificing to bring change. Not the guy in the suit. If he gives us support, well and good. And it will certainly not be the guy in the collar. You can cue his sermons right now.”

“It’s a minority of oppressed people who always fight wars…”

“Yeh, but you’ll be making all our people shoulder that war and suffer regardless without prospect of winning.”

“Then pack up and go home. Apply for your British passports, celebrate the Twelfth, pin on you poppies and vote for the Unionist Party. I, for one, will not!”

John could see truths on both sides but could in no way visualise the goodwill which the nationalists showed the British Army being overturned. That would take a mental revolution in attitude, he thought. When he considered the Vietnam War and other struggles he had a romantic notion of guerrilla warfare and revolution, and these Belfast streets just did not fit the bill.

The words of the speaker kept ringing in his ears: “this isn’t 1916 and the British Army of today is not the Black and Tans.” That was so true.

Stevie had been at sea, on his way home, when he heard about the Belfast pogroms. When his ship berthed at Las Palmas in the Canaries he borrowed £80, a big sum, from a Scottish crew member. Having made some discreet inquiries he met with a shady character in a bar who sold him two .22 pistols and 500 rounds of ammunition. Back in England he smuggled them ashore. At Heathrow Airport before boarding, and while in the queue at the ticket desk, he got to know the name of another Belfast-bound passenger. He tagged the small bag which contained the guns in that person’s name and sent it through. When he landed at Aldergrove Airport he simply reclaimed the baggage as his own.

Back in the Falls Road he showed John the weapons which both of them turned over and over, loaded and re-loaded and endlessly admired. It was these two weapons which had helped cut through red tape and ‘bought’ them their IRA membership.

Behind the barricades both young men had received weapons training in mostly old guns, training given by local men who had spent a few years in the British Army or Royal Navy. On one occasion John brought Jimmy down to the headquarters in Leeson Street where they had a pirate station, Radio Free Belfast, broadcasting rebel music to its listeners.

Four weeks after they had been erected the barricades were taken down. Church leaders had assured local people that the British Army would protect them. With the barricades down a sort of normality returned even though another army was being built in the shadows.

Each night a British patrol would call into Stanley’s bar on the edge of the Falls.

“You’ll have another beer,” said John, encouraging the soldier. “Sure, your patrol’s over for the night.”

“Okay, Paddy. Just one more.”

“And what do you call that part?” asked Stevie.

“Ah, that’s the safety catch and that’s the magazine release. I showed you already how it works. Are you stupid, mate?” he laughed.

“Yep, I’m Paddy Irishman.”

“He’s mad about guns,” said John, “and would love to be in the army, take part in war and parachute into dangerous territory under fire and get the girls. Have you any medals?”

The soldier drank from his pint, then produced a coin and showed them how to begin stripping the weapon. About a dozen other IRA Volunteers had received similar ‘training’ in this rifle and in the Stirling submachine gun from the same man.

After some weeks the John and Stevie became frustrated by the lack of action and republicans arguing among themselves. The uprising, the revolution appeared to die through want of a crisis or intolerable repression.

John asked Stevie what he thought of the situation.

“What do I think of the situation?” Stevie said, after long thought. “Well, it’s a bit slow for me. I can’t see anything happening in the near future and I’m thinking of going back to sea. What about you?”

“I think you’re right. We’ll not be missing anything. And if we do, we can always come back.”

The IRA asked them to watch out for other opportunities to buy arms while they were away and to keep in touch.

They had only been gone a short time when there had been more trouble, this time involving young people in the Falls clashing with the British Army. Soldiers, with whom they had been friendly just a week or two earlier, were deployed in ‘snatch squads’, would come charging out of the barracks wielding batons and attack those involved in protests or throwing stones. In another incident loyalists burned Catholics out of their homes just yards from Hastings Street barracks and opinion was that the army made little effort to defend them.

When in October the British government published a report announcing the disbandment of the B Specials and that the RUC was to be transformed into an unarmed police force it looked like reform was possible, after all.

Loyalists rioted in protest and fought a gun battle with the British Army in the Shankill area where they also shot dead a policeman.