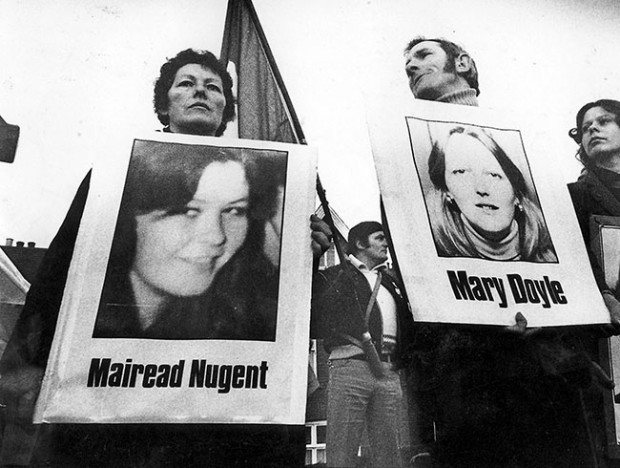

Coming back from visiting my granddaughter (and great granddaughters) in North Belfast at the weekend when I bumped into the indefatigable Mary Clarke (nee Doyle) out canvassing with other women in Ardoyne who are working on Mary’s campaign for re-election to Belfast City Hall.

Mary is one loyal, determined and committed republican, who has been through prison twice, was in jail when her mother was murdered in a sectarian bombing, was on hunger strike, and later spent more years visiting her husband Terence (Cleaky) with her children Marie and Seamus, when Cleaky was in jail for the third, fourth or fifth time.

There’s a film from the 70s called The Way We Were, told partly in flashback over many decades, and at the start of the film Katie is a young political activist, out on the streets, leafletting. Over the years many people change, don’t care, fall away, look after Number One, but at the end Katie, older and as principled as ever, is still campaigning and agitating and protesting for a better world. That was just a film but in the real world it is Mary Clarke who epitomises selflessness, remains true to the vision, and has made many, many sacrifices on behalf of her people.

In 2006 I edited a book of essays on the 1981 hunger strike and in it Mary told the story of a life committed to Ireland and its people. I think it is worth re-publishing, so here it is.

The Feelings Are Still Raw

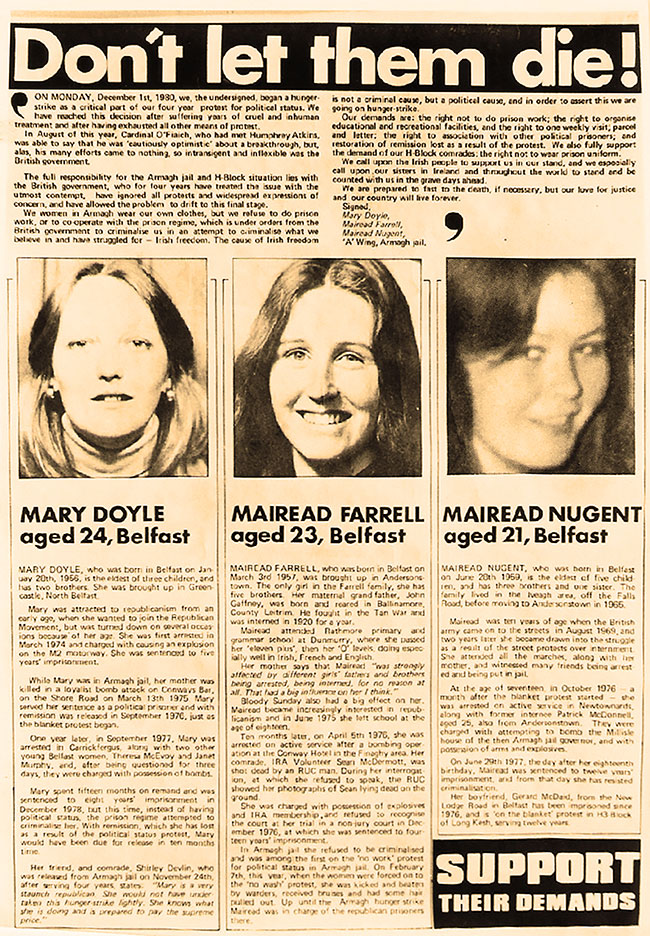

– Mary Doyle, former hunger striker

I was born in 1956 in Catherine Row, one of the few Catholic streets in Greencastle, on the outskirts of North Belfast. I was the oldest in the family and had two brothers.

The Sands lived nearby in Rathcoole. Bobby, Bernadette and Marcella, who’s the same age as me, went to the same school as I did, Stella Maris. I remember Bobby hanging around Greencastle. Little did we know that years later we would be writing to each other from prison.

My mother came from Wicklow to Belfast when she was sixteen to her married sister’s and found work as a domestic servant. She met and married my father there. My parents had no republican background but daddy encouraged us to read, especially Irish history. History was hard to avoid – given what was happening on the streets. On Tuesday nights we used to go to a wee disco up in the school and there was always trouble outside. We would fight with the tartan gangs from Rathcoole, especially the KAI (Kill All Irish) gangs, even though we were outnumbered.

I became involved after internment. In fact, two days after Bloody Sunday I had just turned sixteen and joined Cumann na mBann. I was arrested in March 1974 and charged with the attempted murder of two RUC men. But that was dropped and I was convicted instead of causing an explosion on a bridge over the M2 Motorway and was sentenced to five years in Armagh Prison.

We had political status and the administration recognised and worked with the IRA command structure in the jail through our OC, Eileen Hickey. In Armagh there were remand and sentenced prisoners, internees until 1975, and then there were those on protest after the withdrawal of political status in 1976. I had political status when Mairead Farrell came into the jail in April 1976 and I was released in September just as Mairead was going on protest after being sentenced.

At that time there were over one hundred of us and there was strength in numbers. For example, when the men burned down Long Kesh camp in 1974 we in Armagh took the governor hostage and barricaded the landing until we received reassurances that our comrades were safe.

One night in March 1975 my mammy and daddy went out for a drink in their local, Conways Bar, which was mostly frequented by Catholics but had a few Protestant customers. My mammy was walking out into the hallway when she came across a number of gunmen. Two Catholics had been killed in the bar in a sectarian attack the year before. There was a scuffle as mammy fought with one of the gunmen. Another threw a bomb into the hall.

My mammy was killed outright in the explosion and two customers were badly maimed, with one man losing a leg. She was forty one. Another dozen were injured but daddy who was in the lounge at the back was okay. The bombers were also hurt and one of them, a man called Brown, later died from his injuries.

I was given 24 hours parole. But because of mammy’s injuries I wasn’t allowed to see her. I just came home to a closed coffin. They showed me a box and said, “There’s your mammy.” For a long time I couldn’t accept her death. Years later, after Mairead was shot dead in Gibraltar and her body was brought home, her coffin was sealed. But the family opened it for a couple of us, her former comrades, and we saw her for the last time. It is so important to be able to say goodbye to a loved one.

I reported back to the IRA after my release but was caught within twelve months, along with two others, in September 1977. At my trial I refused to recognise the court and was sentenced to eight years for possession of incendiary devices.

The governors and screws took great satisfaction in telling me I was now ‘a criminal’. I joined Mairead and the others, eventually numbering twenty, on the protest. Unlike the men in the H-Blocks we were allowed to wear our own clothes but for refusing to do menial prison work and take orders we were confined to our cells and restricted to one visit a month. We lost parcels, letters and remission and our full entitlement to association. My father was in ill-health and it was my two brothers and my aunt who visited and looked after my needs as best they could.

The screws were abusive, particularly during cell searches. They seized all clothing coloured black – even though the clothes had come in through the censor – because we would wear black tops and skirts to commemorate the dead on occasions such as Easter Sunday.

In February 1980 the screws escalated the protest by refusing to let us out of our cells to empty the chamber pots. There were two prisoners to a cell and the pots were overflowing. When they opened the doors we slopped it out onto the landing. They moved us to another wing and locked us up there. That’s when the no wash protest started in Armagh. Many of the screws were bad bastards but there were some honest ones who would wonder how it had all come to this, though the answer was no mystery to us.

We had crystal sets to listen to the news but the prisoners who still had political status would shout over to us and we also all met up at Mass on Sundays which was when we got supplied with tobacco and cigarette papers.

During the summer of 1980 the question kept getting asked, what’s next? It was sort of inevitable that the only other avenue we had was to hunger strike. So we talked and talked about it. Mairead, who was our OC, was in contact with the OC in the Blocks and we knew they were talking about it as well.

Mairead Farrell

The time came for people to volunteer. I thought long and hard about it but couldn’t just think about myself. My father was sick and still hadn’t got over losing my mammy. I had to think of my brothers. But I was very, very determined and I wasn’t expecting someone else to do what I wasn’t prepared to do. So I put my name down. It wasn’t done lightly. Wasn’t just a rash decision. I was almost twenty-five so I think I was mature enough. I said to myself, there’s every possibility I will die. It wasn’t a case of, Ach, we’ll be on it a few weeks and Maggie Thatcher will give in. I was never under that impression.

The leadership didn’t want the hunger strike and they sent in all this information about what it can do to you, your body and vital organs. They tried to deter us.

The men went on hunger strike on October 27th. Mairead Farrell, Margaret Nugent and myself joined them on December 1st.

That morning we began, the screws put Mairead, Margaret and myself in a double cell together. The cell was never without food. They took away breakfast and replaced it with lunch. Took away lunch and replaced it with supper, etc. Jail food is notoriously rotten and cold – fat with a bit of meat through it. But all of a sudden the plates were overflowing with steaming hot chips that smelt so appetising.

A screw would say, “Those chips have been counted, so we’ll know if you’re eating.”

They were taking blood samples everyday and weighing us and would have known if we were eating. They were so petty.

We were advised to take salt diluted in the water and to drink about eight pints a day. That first night I was as sick as a dog, throwing up.

We were still writing the letter campaign, calling for support and had a good communications system. I remember someone in the remand wing shouting over to us that it was on the news that John Lennon had been shot dead. Here we we’re sitting on hunger strike and I’m shattered at the death of John Lennon! Mairead was a Paul McCartney fan – who went on to become “Sir” Paul! – but I loved John Lennon!

Going into the second week they moved us to the so-called hospital wing and you had to have a bath. We hadn’t washed in ten months. We were secretly looking forward to a hot bath but the whole pleasure was taken out of it because we felt so weak and it drained us further.

Cardinal O Fiach came into see us and brought us cigarettes. Fr Murray was a brilliant chaplain and without him there were times when I didn’t know what we would have done. He fought for us more so than most of the Catholic Church who let us down very badly. Had they done more the second hunger strike would never have taken place.

In mid-December we knew that Sean McKenna, who was on hunger strike in the Blocks, was very ill. We were listening to the nine o’clock news one night and quickly looked at each other: had we heard right? The hunger strike was over? We were glued, waiting for the ten o’clock news and when it was confirmed we thought our demands had been met. We said, “Thank God, for the sake of Sean McKenna and his family that the Brits have seen sense and recognised us for what we are.”

But then we were paranoid: what if they were just saying that on the radio. So, we decided to keep on the hunger strike. The next morning the screws once again brought in breakfast, cornflakes and mugs of tea, and told us the hunger strike was over. Mairead said, “We’re still on it.”

The governor came in and said that if we were calling it off, “not to be eating that food”, meaning the breakfast. Mairead came back from a visit and confirmed the news and so we ended our hunger strike after nineteen days. A few days later we were sent back to the wing to join the rest of the comrades.

My daddy had been 110% behind me but he couldn’t come up during the hunger strike – it was too much for him. He came up when it was over and you should have seen the relief on his face. He was the happiest man on earth.

As the days went on it was such a kick in the stomach when we realised that the Brits had reneged on their promises. We were angry. Then there was talk of a second hunger strike. We discussed it and Mairead and I decided to put our names forward again.

Then I began to think about it, more and more. You don’t realise what you’re putting your family through and I decided I couldn’t put my family through it again. So I withdrew my name and then Mairead said that she had also reconsidered and would not be taking part. Some of the other prisoners – some serving short sentences – volunteered, but in the end there was to be no second hunger strike in Armagh. We didn’t have large numbers to draw from, like in the Blocks.

For both of us it was an agonising decision because the women were always a part of the prison struggle. We just weren’t “wee girls”, the way some referred to us. I had been writing to Bobby Sands regularly and I remember getting a comm from him. He said that when he heard there wasn’t going to be a hunger strike in Armagh he was the happiest man in Long Kesh. He didn’t mean it chauvinistically, but comradely, affectionately.

Along with the men, we simultaneously ended the no wash/no slop out protest. We were still locked up all day but were allowed out at night and were able to watch the news on television.

When Bobby went on hunger strike we had mixed emotions – pride, terror but, above all, a sense of helplessness. We intensified the writing campaign, lobbying across the world. His election victory gave us a real buzz. We convinced ourselves that this would lead to talks and a resolution of the protest but it didn’t.

In the last days of his hunger strike you were trying to stay continually awake, as if you were on watch. That Monday night I was exhausted and fell asleep. The screws quietly opened the doors at 7.30 the next morning. There was an eerie silence throughout the wing. I went to slop out and in the toilets and Brenda Murphy came in and said, “Did you hear…”

I knew by the expression on her face.

“Bobby died this morning…”

I went back to my cell and just broke my heart. Even though we were expecting it from the reports of how he was deteriorating, it was still unreal. That night we saw the scenes on the news, his poor mother and father. It was so sad but we were so angry that it made us more determined even though we were totally frustrated at having no means to express our anger.

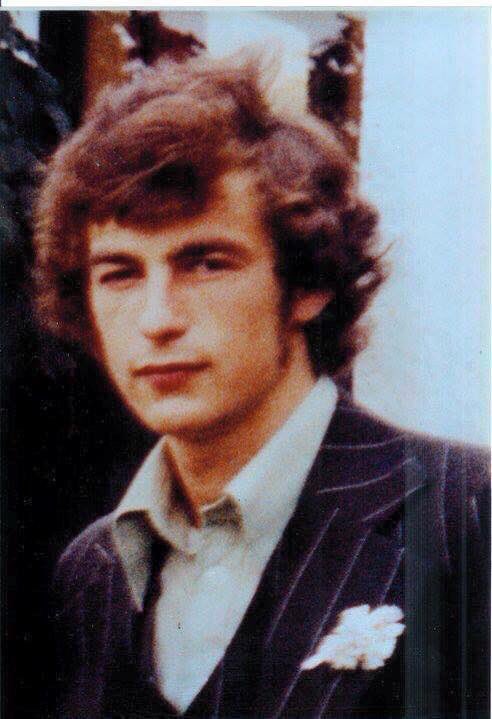

Thomas McElwee

Dolores O’Neill, who was on protest, was engaged to blanket man Tom McElwee from South Derry who was serving twenty years. They had been arrested on the same IRA operation. Tom went on hunger strike after his cousin Francis Hughes died, a week after Bobby. Dolores got a visit with Tom before he died. I’ll never forget the look on her face coming back from that visit. It was heart-breaking.

It never got easier, after each hunger striker died. It tore you apart.

It was a Saturday and I was just called for a visit when I learnt that the hunger strike was over. After seven long months it was over. We all cried. I was relieved that no more comrades would be dying. I was relieved for their families. But I thought of the families of the ten men who had died and how they must be feeling.

It might be twenty-five years ago but it’s like yesterday. The feelings are still raw. And then, after it ended, we got our demands, slowly but surely.

Unless you have been in jail you cannot understand the bond between comrades. I don’t mean that we were anything special. It’s just hard to explain that we were all there for one another. I had my down days, especially after my mammy was murdered. My comrades helped me through and I would have been lost without them. I never had sisters but there are some of those women whom even if I had had a sister I couldn’t have been closer to.

In 2011 Mary Clarke stood for Sinn Féin in North Belfast and was elected a Councillor to Belfast City Hall. She is again running for Council this Thursday