I reviewed Richard Flanagan’s novel The Sound Of One Hand Clapping for The Examiner in 1998 and didn’t like it. So, eagerly because of all the praise it had received, but with some reservations, I plunged into The Narrow Road To The Deep South.

I still have problems with Flanagan’s style, use of time and point of view and was glad I read the novel which won the Man Booker Prize, 2014. But I found myself in agreement with many of the criticisms made in a devastating review in the London Review of Books by Michael Hofman.

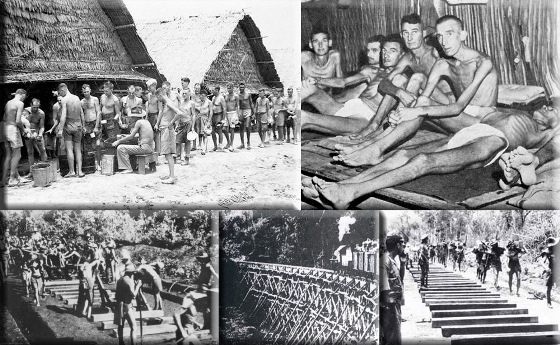

The main character is an Australian military surgeon, Dorrigo Evans, who is captured in South East Asia during WWII, becomes a POW and along with thousands of others is brutally put to work on the Thailand-Burma Death Railway. The descriptions of the cruelty, the hunger, the cholera, the privations, the lice, the ticks, the ulcerated limbs and amputations and casual death, are harrowing. Even so, I found myself equally curious, and would have preferred more, about the fate of some of the Japanese officers post-war and their attempts to escape the war crimes commission.

One of those who is caught, a Korean collaborator who maltreated the prisoners, is sentenced to death as a Class B war criminal. However, it doesn’t escape his notice that “the Allied victors often seemed to free officers who had links with the Japanese nobility and let others more lowly, like themselves, be the scapegoats whom they hanged… Why did the Americans support the Emperor but hang them, who had only ever been the Emperor’s tools?”

The title of the book is based on a seventeenth century haibun (a mix of prose and haiku) by Japanese poet by Matsuo Basho, Oku no Hosomichi, which translates as The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

Evans recalls a brief love affair he had with Amy the young wife of his uncle, the memory of which helps sustain him through his ordeals and outlasts his imprisonment and insufferable marriage.

There were some passages I thought very well written.

This one is Evans’ observation about the relationship between Amy and his uncle: “She glanced at her husband, a look in which Dorrigo glimpsed a complex mud of intimacies normally invisible to the world – the shared sleep, scents, sounds, the habits endearing and frustrating, the pleasures and sadnesses, small and large – the plain mortar that finally renders two as one.”

Evans’ thoughts on violence reminded me of a passage from my own novel, Rudi, on the same subject.

Flanagan writes: “For an instant he thought he grasped the truth of a terrifying world in which one could not escape horror, in which violence was eternal, the great and only verity, greater than the civilisations it created, greater than any god man worshipped, for it was he only true god. It was as if man existed only to transmit violence to ensure its domain is eternal. For the world did not change, this violence had always existed and would never be eradicated, men would die under the boot and fists and horror of other men until the end of time, and all human history was a history of violence.”

I wrote: “His [Rudi’s] father had said that all wars were mostly dirty affairs and only a minority of combatants ever acquitted themselves with honour or distinguished themselves with their bravery… His father had always insisted that there was nothing intellectual about warfare. Lyrical words, editorials, orations, sermons, could never sanitise it…

“What annoyed Rudi was that the armed man throughout history was seen as charismatic and seductive… [And] he regretted how warfare, above the influence of culture, fundamentally shaped the history of humanity and would continue to define the world.”