The journalist Brian Rowan has reviewed West Belfast on Eamonn Mallie’s website. Here is the feature in full.

The re-written and re-worked novel West Belfast is a story about how the ordinariness, the kindness and the innocence of this place became shattered.

The re-written and re-worked novel West Belfast is a story about how the ordinariness, the kindness and the innocence of this place became shattered.

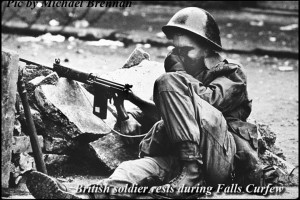

Its setting is the sixties – stretching into the early seventies.

A story about tugs of love and war.

Danny Morrison’s novel was first published in 1989, and has been re-shaped in a 25th anniversary edition.

His story-telling grows from his roots in the Falls Road community and then his background in the IRA and in republican politics, but it begins before then – before the first shots were fired or bombs exploded. Its starting point is an adventure in the Belfast hills – young kids out exploring – seeing the geography of the city begin to take shape in their minds.

“The realness of it all, the Sundayness of it all, gave the picture a quality which could only have been appreciated from this height and at this distance. It was breath-taking,” Morrison writes.

In the page turns, you also read about the realness of family struggles, struggles related to work and money – trying to make ends meet at Christmas. There is nothing imagined or fictional or unreal about this. Those of us who know and remember the working class streets of the city back then, know there was little but, despite this, there always seemed to be just enough. People got by, people who lived and survived and held together as communities.

There is a love story woven throughout the pages of this novel, told in the young lives of John and Angela – a broken love and then a letter of hope.

Then, there is the ruthlessness and the rawness of an exploding conflict, told from a particular background and perspective by Morrison, but a story that can read across into other communities, and regiments and police families. Many mothers cried the tears that Catherine cries for Jimmy in Morrison’s book.

In real life, away from the pages of a novel, the loyalist David Ervine talked many times about the “something” that “happened” here. What he meant was that ordinary people – loyalist, British, republican were dragged into a war – into something that changed many lives and broke and destroyed and took many others.

Another loyalist William ‘Plum’ Smith, author of the recently published Inside Man, has spoken and written about being “born into conflict”. He too remembers the innocence and the ordinariness of Belfast before the wars.

There are ghosts in Morrison’s novel and ghosts in the realness of what happened here.

The long peace hasn’t exorcised the memories of the long wars.

Morrison describes ghosts that broke health and minds. And, there is a line he uses as Angela breaks-up with John.

“The truth would have wounded him even more.”

Think about that sentence and those words, not in terms of broken love, but broken bodies – the brokenness of conflict and the past.

Will ugly-truths make things better or worse?

Books – fiction and fact – written by many, including Morrison and Smith, give us an insight into not only what happened, but why it happened.

There is much reading and learning between their lines.