The Irish Examiner today published a feature I wrote about the meaning of and legacy of 1916. Here it is:

No one, not the IRA, not Sinn Féin, not Fianna Fail or Fine Gael, or any party or organisation, owns or has a monopoly on the Rising or its legacy.

But you can see from the reactions and opposition to the powerful re-enactment of O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral through the streets of Dublin last August that someone “fears to speak of Easter Week”, that someone is embarrassed about 1916 and all that.

And you can understand why Irish republicans would want to give due honour to those brave men and women who fought, if others lack the enthusiasm.

The government’s very first foray into the commemoration was disgracefully to produce a video about 1916 which didn’t even mention the names of the signatories and those who were executed. What a glaring but telling omission. It would like be talking about the Cuban Revolution and omitting the roles of Fidel Castro or Che Guevara. Or talking about the struggle against apartheid and omitting Nelson Mandela.

But those GPO veterans who the government did manage to include in the video were such strapping physical force republicans as Field Marshall Bono, General Bob Geldof, Queen Elizabeth, David Cameron and the late Ian Paisley.

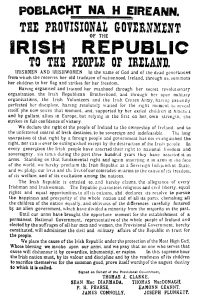

The government also managed to turn the Proclamation into gibberish by using Google to translate it into Irish. The government is certainly free to do its own thing in its own peculiar way, as are others. But what the government fears most is an analysis and debate about why the Rising was the proper reaction to what was happening at that time. It fears – with some justification – the drawing of certain parallels.

For all its good intentions the failure of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) to understand imperialism and colonialism, that party’s flawed and damaging compromises, showed that its leaders were putty in the hands of the British. It had played by the constitutional rules, had assiduously, peacefully and patiently for decades worked hard for Home Rule and its position had been overwhelmingly endorsed in nine successive general elections across the 32 counties of Ireland.

Unfortunately, the IPP swallowed everything it was told, and that included buying into the War, recruiting and sending 300,000 Irishmen to the trenches of France and Gallipoli who believed, naively, that by fighting, Ireland would get a better post-war deal.

In 1914 Redmond accepted the exclusion of four counties of Ulster, then in talks in 1916 Lloyd George got him to agree to include Tyrone and Fermanagh, bringing the number of excluded counties to six – allegedly, on a temporary basis during the emergency period of the war. However, in talks with Edward Carson Lloyd George assured the unionist leader that the exclusion of six counties was to be permanent.

But there were other Irish men and women, like Pearse and Connolly and Markievicz, who had the measure of the British government, and who knew that once the war was over, Ireland’s sacrifices in the trenches would be forgotten. They saw the necessity of striking out at Easter 1916 and staking a claim regarding the freedom of this small nation.

But there were other Irish men and women, like Pearse and Connolly and Markievicz, who had the measure of the British government, and who knew that once the war was over, Ireland’s sacrifices in the trenches would be forgotten. They saw the necessity of striking out at Easter 1916 and staking a claim regarding the freedom of this small nation.

Even before the run-up to the centenary of the Rising we got a taste of the distaste to the honouring of our patriotic dead. Ten years ago at the re-interment of Kevin Barry and nine other IRA Volunteers in Glasnevin Cemetery, one Sunday newspaper asked, “Why could they not be exhumed and reburied in private?” The funerals, wrote another leading commentator, will offer “a great boost to those who want us to feel that the only difference between a terrorist and a patriot is the passage of time.”

So now we are getting to the crux of the matter: whether there are any parallels between the aims, objectives and modus operandi of the IRA during the War of Independence, and the IRA’s armed campaign in the North from 1970 until the ceasefire.

To justify or to sympathise or, at the minimum, to understand 1916, is to justify, sympathise or, at the minimum, understand the IRA’s armed struggle in the North. It is inescapable, regardless of what sophistry is employed to argue otherwise.

But the IRA didn’t need that comparison to justify itself: partition did that.

If 1916 was about the denial of freedom and British misrule in Ireland, the recent armed struggle in the North was about the denial of the same freedom and a more egregious form of British misrule in the form of partition with its ‘Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’. Where a Prime Minister could boast that he wouldn’t have a Catholic about the place.

In Ireland’s major cities prior to 1916 there was, of course, extreme poverty and high unemployment. There had been two deaths in baton charges during the Dublin lock-out in 1913, which preceded and helped define the radical nature of the Proclamation. There had been three deaths at the hands of the British army after the Irish Volunteers’ Howth gun-running incident in July 1914.

So what did northern nationalists suffer in comparison? Fifty years of humiliation; the physical persecution of any outward expression of their identity; discrimination in housing, employment and investment; its minority position entrenched; a people denied access to government or power to change government; more deaths than occurred in Dublin prior to the Rising, deaths at the hands of the RUC, B-Specials, loyalists and the British army, long before the IRA re-organised and launched its armed struggle.

Debate around commemoration also exposes just how little successive Dublin governments have lived up to the principles enshrined in the Proclamation or pursued the cause of Irish independence and reunification. Celebrating 1916, triggers certain imperatives, including an examination of the malignity of British rule in Ireland, the divisions it caused between brothers and sisters, families, communities, political parties.

It is easier to repeatedly attack Sinn Féin, and internalise our problem, than it is to confront the British government on collusion, its agencies’ involvement in bombings and assassinations, including the killing of dozens in Dublin and Monaghan.

We have yet to achieve full independence; we are still undoing the damage which partition wrought on our people, nationalist and unionist, who from their respective positions paid heavily for this division and the political mistakes of the past. We have all hurt each other.

But we have, undeniably, come a long way. Peace has come ‘dropping slow’. The state I live in is not the state I grew up in – it has been transformed. But it has not been transformed enough. We still have major problems socially, economically and politically, but none that we cannot redress through skill, good political leadership and patience.

If Sinn Féin and the DUP can share power in the North, given our bloody past, then isn’t it about time that Fine Gael, Fianna Fail and Labour ‘cease-fired’ in the South, stopped using the Troubles as a substitute for political debate, and simply agreed to disagree about the legacy of 1916 whilst honouring the undoubted bravery of the men and women who fought at Easter Week?