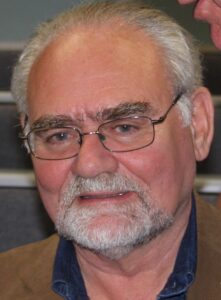

Former IRA prisoner Pat Magee reviews the recently published and highly-acclaimed memoir, Bless Me Father—A Life Story by the singer/songwriter, Kevin Rowland.

-oo0oo-

The Royal Festival Hall, Southbank Centre, London, 29 April 2016. I’m attending Imagining Ireland, part of the centennial commemoration of the Easter Rising, a celebration in words and music of the Irish soul. President Michael D is there, somewhere. Hard to tell from my Level 4 Side Stall.

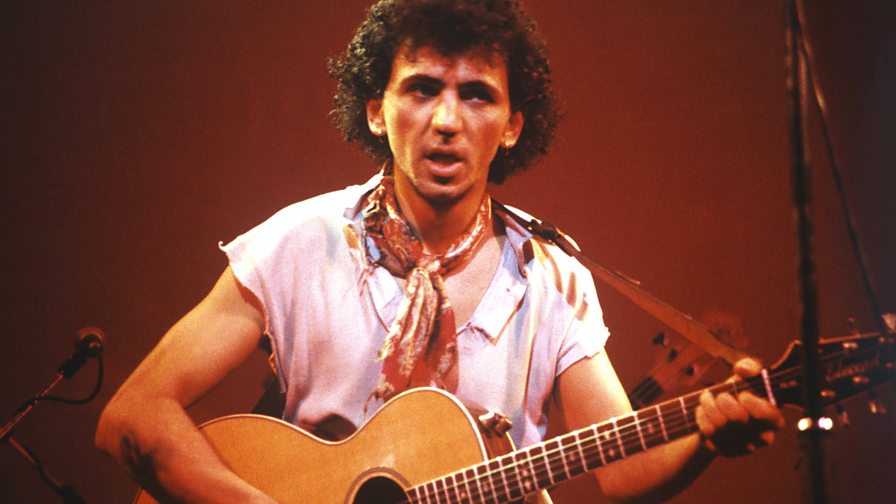

On stage, a richness of talent on parade—including Paul Brady, Martin Hayes, Andy Irvine, Lisa O’Neil (new to me—a troubadour from Cavan). And Kevin Rowland. Without Dexys Midnight Runners to front.

That voice! (‘Gino’ and ‘Come on Eileen’, distinct in my aural recall despite the intervening decades.) Now solo, singing ‘Carrickfergus’! Best avoided, except by the best. He owned it—loss, a ‘cry’. No compromise with any traditional rendering. The look, too, was different. For the occasion, a black Crombie and duncher. An homage in keeping with the moment? Another re-Imagining.

Reading Kevin Rowland’s recently published memoir, Bless Me Father, is part of a long overdue catch-up. I admit to being bypassed by much of the youth culture of the late 1970s and early 1980s (for reasons not strictly relevant).

He opens with a look and a sound, his first key influencers, aged eight, of ‘greased … quiffs’, James Dean and Elvis. Style and music thereafter guide his creative destiny.

Born near Wolverhampton in 1953 to Irish parents, Kevin Rowland’s first memories are of Mayo, where his mum returned with her young family in 1955; his dad, a builder, having remained in England to recoup from a business failure. After two years of separation, the family reunite in England.

Ireland, clearly from Kevin’s account, is a core identifier: Irish Catholic, Sunday Mass-going family, with one uncle a priest (another, ‘a gentleman of the road’); and Kevin, early, having had a nascent ‘calling’ for the priesthood. His, though, was a troubled childhood. Petty theft, vandalism, leading to appearances in juvenile court (and later, more serious offences, some involving violence); and under-achievement at school, due in part to a form of attention-deficit that too often occasioned the disapproval of a stern, belt-wielding father. The boy grew up seeking dad’s approval.

Mum instilled a sense of the Irish people’s long endurance and resistance: ‘She showed me the bullet holes in the wall where the 1916 rebels had boarded themselves in, proclaiming an Irish Republic and an end to British rule. I was touched by it …’

Kevin much later in the book reveals that his father was of a similar political mind.

Symmetries abound with my own upbringing of what it was to be Irish in England. I may have registered for a bed in the same ‘Spike’ in Peckham he later mentions. The sense of alienation, of displacement, conveyed by Kevin, is not unique, and may strike a chord with many of a similar age and background. Different paths, for sure.

Kevins’s way through the confusion of identity was to focus on a growing realisation of his gift for performance, of singing and song-writing, and for an inimitable fashion sense.

An apprenticeship with Punk inspired Kevin that Soul was the next thing. With a nucleus of a band, self-styling as a gang, he honed something unique to the moment, in look and sound, which brought Dexys Midnight Runners’ ‘Gino’ to No 1 on Top of the Pops, a dream fully realised.

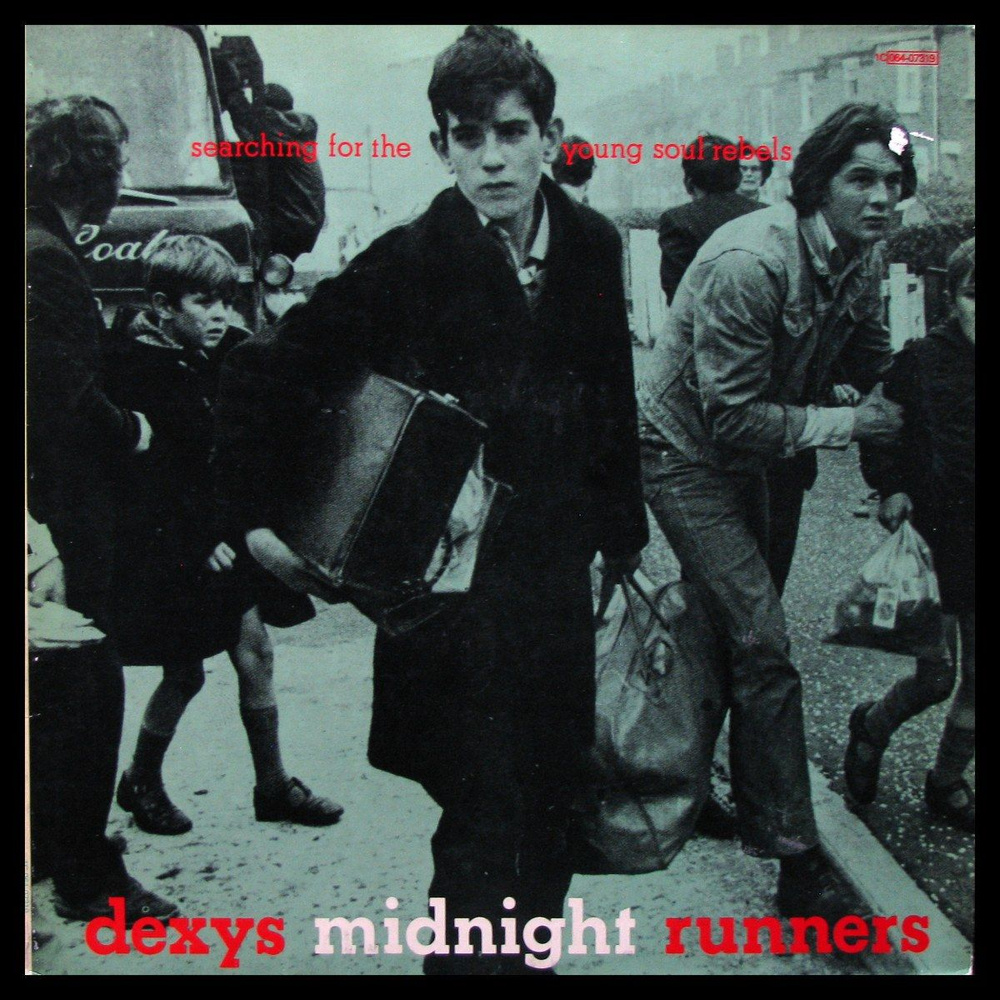

Then a brilliant debut album, ‘Searching For the Young Soul Rebels’ (1980), the cover depicting a child forced from home during the Belfast pogrom of August 1969. The next album was, ‘Too Rye Ay’ (1982). The achievement was a body of work consciously informed by his Irish roots and grasp of history, as further exemplified in ‘Burn It Down’, pointedly citing the Irish literary canon (à la Brendan Behan), in anger at the anti-Irish trope of ‘the thick Paddy’. This was some five years after the Birmingham pub bombings. As Buffalo Springfield put it, ‘There’s something happening here’. Then there were The Pogues, The Smiths, Oasis, agus araile. And before them, The Beatles. Voices of the second generation Irish.

The band soon won international acclaim. Kevin set the look, hopping from New York docker to dungareed rag doll in ‘Come on Eileen’, assumed as an anthem for Eileens everywhere (without, perhaps, too sharp a grasp of the lyric intent).

Tensions began to tell. Had the band peaked too early? Success for Kevin didn’t translate into a sense of accomplishment or of personal satisfaction. (His dad’s seeming indifference to his son’s new status was withering.) Stylistic and musical differences were to surface. Some members weren’t motivated enough for the total commitment demanded by Kevin. He was accused of ‘control freakery’. On one occasion, he fell out with two of the band, ordering their girlfriends off the tour minibus for breaching a supposedly agreed policy in these matters. This is really not how I might have envisaged touring etiquette. He later reveals, inconsistently, some experience with groupies, but by then drugs come into the picture. He must have been a nightmare. He also crossed David Bowie, an early inspiration. Then there were management issues and claims of financial irregularities.

During these years, Kevin became increasingly aware of what was happening in ‘the six counties’. Of the H-Block protests and the massive support in Ireland and internationally for the Irish republican POWs’ demands for political status. Of ‘the bravery of Bobby Sands’ and comrades. At some point Kevin joined Troops Out, attending meetings and demos. This absorbing political interest seemed to coincide with a period of decreased creative spirit.

Last May, along with other artists, Kevin signed an open letter supporting Irish rap trio Kneecap’s right to express themselves and just last week he appeared with hundreds of other supporters outside Westminster Magistrate’s court where the group’s Liam Óg Ó hAnnaidh was again remanded on bail under a fraudulent ‘terrorism’ charge.

By 1983 the writing was plastered over the gable end for Dexys. After their eventual break-up Kevin spiraled downward into a near decade-long blizzard of drug addiction—cocaine, mainly; some heroin—during which he lost everything gained from his creative heights: a host of friends; the break-up of several relationships, including that with Helen O’Hara, Dexys’ fiddle maestra. He was declared bankrupt, losing his flat. He hit bottom.

Then the slow, agonising retrieval. Part of the road back involved psychotherapy, under which he discovered his role as ‘Scapegoat’ in a harmful family dynamic. There was a lengthy spell of solace within the Brahma Kumaris, until belatedly hearing of their vow of celibacy. The greatest healing seems due to the help of a hostel-community in which he received guidance on his addictive behaviour. As a result, he adopted the Twelve-Step programme to recovery, which entails reflection on all the harm caused by the addicted, conflicted, obsessive character, leading to the pursuit of forgiveness through atonement.

Bless Me Father, is the culmination of a search for self-awareness undertaken twenty years earlier, a mea culpa for a litany of commission and omission.

Kevin Rowland writes with an engaging candour. He emerges as a contemporary touchstone of change. A challenging artist. It’s there in the music. In the habitual re-invention. As a performer.

Now in his own telling.

-oo0oo-

Pat Magee served fourteen years in British prisons, convicted of the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing targeting Margaret Thatcher and her Cabinet. He is the author of Gangsters or Guerrillas? Representations of Irish Republicans in ‘Troubles Fiction’ (2001), and Where Grieving Begins: Building Bridges after the Brighton Bomb—A Memoir (2021).

Pat Magee served fourteen years in British prisons, convicted of the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing targeting Margaret Thatcher and her Cabinet. He is the author of Gangsters or Guerrillas? Representations of Irish Republicans in ‘Troubles Fiction’ (2001), and Where Grieving Begins: Building Bridges after the Brighton Bomb—A Memoir (2021).